TransVision 2004 Coverage PART ONE: A RAMBLING OVERVIEW OF TV2004

|

“Transhumanism is a way of thinking about the future that is based on the premise that the human species in its current form does not represent the end of our development but rather a comparatively early phase.”

– Prof. Nick Bostrom, Oxford University

|

Below are a few photos we took at TransVision. I felt a little bit like a “science groupie” asking people to let me take a photo with them, but hey, it was exciting for me! I should also note that in this article I’ve barely skimmed the surface of most of these brilliant minds — I strongly encourage you to check out their websites and google them for more.

Steve Mann (wearcam.org) speaking about wearable computing, glogging, and sousveillance. I really urge you to visit his websites to learn more about how he’s augmenting and mediating the human experience using a cyborg body.

João Pedro de Magalhães of Harvard Medical School talking about his work in trying to find — and one day cure — the genetic causes of aging. You can see in this picture how unfortunately empty the event was.

![]()

![]()

Dr. Rafal Smigrodski (Gencia Corporation) talking about his work on mtDNA replacement which could cure diseases such as Parkinson’s, Alzheimers, and diabetes, as well as dramatically extending lifespans.

![]()

![]()

Biogerontologist Aubrey de Grey talking about life extension by “cleaning” our cells of the toxic aggregates that our bodies are currently unable to deal with. Great beard, great mind.

Allen Randall’s talk on “Quantum Miracles and Immortality” included discussion of a number of amusing thought experiments. In simple terms, quantum theory suggests that all possible states exist at once (ie. there are multiple worlds, like in that show Quantum Leap). Therefore, if you try to kill yourself in a way that has an (impossibly high) high chance of success in every one of these worlds, only the immortals survive — thus creating a quantum state that favors your immortality. I’m not really sure if this talk was supposed to be serious or just really funny, but I enjoyed it and I’ve always been a sucker for philosopher mathematicians.

Torsten Nahm from Bonn, Germany talking about aging, and arguing that being biological (wetware) sucks because of that aging. By moving into a digital form, we can become immortal, make backups of ourselves, experiment with different lives, and anything else we’d like. However, we need to decide whether the transition from one form of being to another involves not only rebirth, but death.

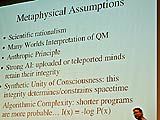

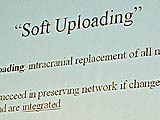

Ben Hyink’s talk on preserving network integrity during the process of uploading. That is, how do you keep an entity alive and conscious as it transitions into a new body? Unfortunately like many of the plenary talks, Ben was not able to fit all of his interesting ideas into the allotted time.

![]()

Anders Sandberg introducing Nick Bostrom’s closing talk. I first interviewed Anders for BME back in I think 1996. Anders’s enthusiastic online promotion of transhumanism has introduced thousands and thousands of people to a more forward-leaning way of thinking. I really liked Anders, although I only got to speak to him briefly. Super nice guy… actually, everyone I met at the event was really nice.

![]()

![]()

![]()

Nick Bostrom of Oxford University and the WTA puts transhumanism — and our need to embrace it — in simple and convincing terms in his closing talk. Nick is also the author of the transhumanism FAQ which is an excellent introduction to the subject along with Anders’s pages.

With George Dvorsky of Betterhumans, one of my hosts (Simon had already slipped out; I’d hoped to include both of them). As well as his work with Betterhumans, you may also want to check out his personal site and blog.

With Rudi Hoffman, “Cryonics Insurance Specialist”. I really got a kick out of Rudi — as much as he’s a real cliché of a salesman, he’s a a lot of fun and an incredibly enthusiastic spokesman for jumping into the future by jumping into a vat of liquid nitrogen. Contact Rudi if you’re trying to find an affordable way to have your brain — or entire body — frozen Futurama-style.

A group photo taken near the end of the event. Shannon Bell is on the far left (when I mentioned that Shannon had joined us to friends, they were extremely excited — she has a reputation for being one of the best professors you can have at York University, as well as being a distinguished author and researcher). In the middle of the front row is Stelarc who you’ll meet in more detail in part two of this article, and between them is José Luis Cordeiro who will be hosting TransVision 2004 in Caracas, Venezuela.

Transhumanism, at its simplest, is a way of thinking and being that embraces the idea that our experience as homo sapiens is just one small step in an ongoing evolution, and that we should take an active rather than passive role in “making ourselves better”. Transhumanists are a mix of philosophers, futurists, sci-fi buffs, and bona fide scientists advocating ideas such as uploading (the transfer of consciousness into computers), genetic enhancement, immortality, machine-human integration, and nanotechnology. Body modification culture lies on a related path and represents a real-world application of breaking the biological mold and transforming ourselves into something we perceive as “better” than what nature gave us.

TransVision, the yearly convention of the World Transhumanist Association, took place in Toronto, Canada for 2004 and BME was there thanks to an invitation from our friends over at BetterHumans. It took me a moment to actually figure out where it was being held, because nowhere on their website did it list an address or even the name of the building that was being used — but, after a bit of googling for the JRR McLeod Auditorium, we made our way to the University of Toronto Medical Sciences Building.

The conference had drawn speakers from all over the world — a sizable European and Scandinavian contingent, South Americans, and of course plenty of Canadians and Americans. It seemed to touch on every demographic from young fashionable cyberpunk kids, übergeeks, scientists, artists, and one seeming half-wit conspiracy nut that asked “how many methods of human improvement are there”, besides “chemical augmentation” (which he certainly seemed to be enjoying) at every talk he attended. One thing that surprised me was how empty the event was and how few people other than the speakers seemed to be there — many of the talks I would attend had less than twenty people sitting in the auditorium, with most of the seats empty.

After picking up our press passes, Phil Barbosa (who’d joined me to help film the event) and I went to the front row to wait for the opening talk by Steve Mann to begin. Steve Mann is the real deal. A genuine geek that looks every bit the part, Steve Mann has lived with wearable computing and camera technology since the mid 1970s and is a leading — and seed — researcher in these fields. He’s vehemently anti-corporation, is a political activist on surveillance issues, as well as being an environmentalist using guerrilla installations of solar cells and wind turbines.

Mann concentrated his talk on what he’s best known for: glogging, or “cyborg logging”, a form of literature (if that’s the right word) that predates but closely resembles blogging and moblogging and mandates that the glogger extend their body and consciousness into artificial and reconfigurable appendages. Using his wearable computing and media system, sometimes in collaboration with other cyborgs, he explores, documents, and shares his view of the world he sees. His inverse surveillance or sousveillance (“watching from below”) regularly brings him in conflict with those watching from above — he observes that those who run their own surveillance cameras are usually those most offended at his sousveillance of them in return. Mann went on to talk about “dusting”, a slightly improved version of an additive compositing technique that’s been in common use since the beginning of photography, which he seemed to think was important. This illustrated one of the pitfalls about becoming so engrossed in personalized technology while being heralded as the primogenitor — a difficulty in recognizing or taking seriously work done by other researchers.

As much as Steve Mann gave a largely brilliant talk, it also illustrated a fundamental problem in passing knowledge and ideas from hardcore geek culture to the mainstream: it’s not that charismatic (Reason magazine described Mann as “rather creepy” and spoke of him derisively in their event report). Steve displays a sense of humor that’s highly personal and a difficulty in communicating with other humans, which is genuinely ironic given the amazing tools he’s helped developed to facilitate these communications. His websites are ugly and primitive, the photos of him wearing his inventions are “unflattering” to say the least, and he uses common terms in ways that are awkward and unconventional (such as his insistence that Linux and other open source programs are not software, because wares are items of commerce — better tell that to the open source software movement). The best chefs understand that the way they present their dish greatly affects diners perception of it… Scientists need to embrace the reality of human interaction and start to include marketing as an important part of transhumanist dialog. Body modification for example is successful not just because it’s “right”, but also because it’s cool and accessible.

The title of Steve Mann’s talk had been “Glogging: Sousveillance, Cyborglogs, and the right to self-modification.” The right to self-modification is of course something that I’m very concerned about since it affects the readers of BME (and myself) on a daily basis, and is one of the key points where transhumanism and body modification intersect. Ultimately if we’re going to leap forward from these dirty ape fleshbag bodies of ours, we have to embrace the right of every individual to transform themselves in any way they see fit, be it a split tongue or be it a robotic tongue. Unfortunately, Mann hadn’t mentioned a word about it in the talk, which I found odd given that it was part of the title, so I asked him about it afterwards — given that in many parts of the Western world, even traditional “self-modification” like tattooing is illegal, was there any movement inside transhumanist circles to politically fight for the right to self-modification?

While Mann didn’t know of any such battle, he does have an interesting counter-attack to those who tell him he has to remove the electronic parts of his body — he says “sure, but only if you sign this form assuming liability if I’m injured due to not having them.” It’s a curious idea — if an augmented human is “more” than an unaugmented human, does that mean that in relative terms a normal human is handicapped? Is taking a cyborg’s electronics away the same as telling someone they can’t wear their glasses, or can’t ride on their electric wheelchair? Since we can always improve, where does one draw the line — and should one draw such a line at all? If we’re thinking along such paths, is not genetically improving your child a modern form of child abuse? Or will political correctness force us to define “human” as “stupid and limited, and that’s how we like it?”

Later in the conference I attended a talk by Dr. Rafal Smigrodski, a specialist in mitochondrial genome manipulation. In “how to buy new mitochondria for your old body” he describes what he believes could add a decade or more to people’s lifespans, as well as curing many mitochondrial disorders using a technique not so different from the Keith Richards urban legend in which he solves his heroin addiction by flying to Switzerland where all of his blood is removed and completely replaced with new, healthy, and unaddicted blood. Dr. Smigrodski touched on the right to self-modify issue as well, pointing out that he’s been forced to concentrate his research on those with diseases or otherwise improperly functioning physical forms — and that convincing governments that aging is a disease will be far from an easy thing, even though aging appears to be a terminal condition that we all suffer from. I think it was Nick Bostrom that would say later in his closing remarks that most people have a Stockholm Syndrome type relationship with aging, whereby they give artificial value to that which has imprisoned them.

From my point of view, the right to self-modify is something that transhumanist researchers should be embracing. It’s all well and good to develop technologies that ease the suffering from extremely rare disorders, and maybe that gives us “expendable” people to experiment on (it’s a terrible way to put it, but if we use the ill as fair game to do our early experiments on, that is what we’re doing), but until these technologies are available in unrestricted form to the general public, they’re not particularly transhumanist. Perhaps I’m speaking callously, but in my opinion, if we’re to move humanity forward, we should be concentrating on transforming the best of humanity into something even more, rather than trying to alleviate suffering in that tiny, tiny minority of people who are born with terminal or crippling diseases.

Aubrey de Grey as well gave a fascinating talk on “removing toxic aggregates that our cells can’t break down”, but he as well must face these same issues — how do you start using these technologies to enhance humans, rather than just fixing them when they break? I don’t want to keep repairing my old Ford Escort… I want an upgrade to a flying Lamborghini.

I’d come into the conference assuming that most transhumanists shared my own views: that we should be aggressively transforming humans into the things we dreamed of as children slumbering after spending the day reading science fiction, beings with far more power and options than we have as humans. However, there’s certainly no agreement inside transhumanism that this is the right goal. Mark Walker, editor of the Journal of Evolution and Technology and research fellow at Trinity College, spoke on the Genetic Virtue Program which he proposes is “the only hope on the horizon that humans might remove themselves from the slaughter bench of history.”

The basic idea is that since behavior is at least thirty to forty percent inherited (so you will act like your parents) and thus genetic in nature, that by using genetic manipulation we can, in time, breed a race of humans that are more compassionate and loving, and less aggressive, greedy, and prone to lying (and presumably sinning). While there is a certain truth to Walker’s proposals, the idea of using science to limit humans rather than expand them wasn’t really received that well by the audience. I pointed out that historically progress tends to be made by selfish, aggressive, and sometimes even “evil” people, and that breeding a society of well behaved losers might not be in our best interests as a species. One neurologist in the crowd pointed out that the ability to lie was an important part of an advanced mind, closely linked to the ability to consider different variations on the same idea, and that attempts to genetically force moral behavior might have to sacrifice intelligence in exchange — but Walker’s ideas certainly underscore the fact that there are a myriad of ways to move humanity forward (as well as many definitions of “forward”), and that transhumanism covers a very broad range of politics and faiths.

As is probably clear, I enjoy the hard science, and I believe that we must embrace the absolute right to use that science to better ourselves. To me, that’s the whole point — if all science does for us is fix people who are born “broken”, then we’re actually moving in the wrong direction. While I certainly hope that we can care for all people, if resources are going to be poured into improving humanity, I’d like to see it poured into improving the best humans, thereby moving us into the future. Because of this, I was looking forward to seeing Natasha Vita-More’s “posthuman prototypes debate their own design.”

When Natasha got on stage, more flash bulbs went off than at any other talk I’d been to. With zoom lenses fully erect, an army of transhumanist men showed they were still slaves to testosterone — Natasha lives in a transhumanist body herself with obviously “augmented” mammalian features and a clear attention to fitness and form. I don’t say this to be crass — the mass appeal of extreme cosmetic surgery is very relevant to transhumanist bodies and I was looking forward to hearing her thoughts on it. Unfortunately her talk was rubbish and full of sloppy thinking and inadequate research. She’d “interviewed” a number of fictional and non-fictional post humans, including her own imaginary creation “Primo”, Agent Smith from The Matrix, and Honda’s Asimo robot.

She “asked” these entities what they thought about themselves, humans, and so on, and in her answers made it clear that she had little comprehension of the technology involved, and was primarily interested in making her own sadly uninformed comments. Most obviously she claimed that Asimo was a primitive machine that could do no more than walk up and down stairs, a foolish statement to put it politely. Her commentary on the other technologies was equally ignorant, and her own “Primo” creation showed that she couldn’t even use the terminology correctly (ever get annoyed at the technobabble in Star Trek?) let alone illustrate it in a way that anyone can take that seriously — even if you’re just an “artist”, you still have the responsibility to understand the language you’re speaking. This saddened me, because Natasha is clearly a brilliant and creative women, but she disgraces herself when she speaks so foolishly.

Unfortunately Natasha was not the only person speaking this way at TransVision. I suppose that’s to be expected when you have a wide range of people commenting on such a diverse subject, but what disturbed me about it was that few inside transhumanism seem to have the courage to shout out “the emperor wears no clothes”, but instead seem to prefer a circle-jerk where everyone congratulates each other on how clever they are with little willingness to look at the thoughts critically — although they’ll galdly rip to shreds outsiders who criticize them.

In my opinion, transhumanism doesn’t need ill-informed people who go off on flights of “what if” fancy. You know what? All of us have been doing that since we were five years old. What transhumanism needs is transhumanists. Not people who talk about. People who do it. I have enormous respect for people like Steve Mann and Stelarc (or Todd Huffman with his magnetic vision) who are actually out there living transhuman lives and having transhumanist experiences, rather than just talking about them without any first-hand knowledge, as well as the scientists doing the foundation research that will make it possible. I am not convinced that the philosophers and artists are any different from science fiction authors — an important element in inspiring people to live as transhumanists, but no more than that.

As much as the conference was utterly unpromoted and almost unattended, there was an abundance of fascinating characters. Sitting next to me at several of the events was the boisterous and friendly Rudi Hoffman who was there selling life insurance for those seeking cryogenic suspension with Alcor — for about $40 a month you can buy an insurance policy ensuring that upon death you’ll be frozen a la Han Solo. Unfortunately the insurance doesn’t cover the cost of bringing you back to life — it’s hoped that future generations will do so for you. But still, your chances for reincarnation, as slim as they may be, are a lot better if you’re preserved in a vat of liquid nitrogen than if you’re rotting in a pine box buried in the ground.

Also sitting next to me — in the front row — for several of the talks was a tall, slender Asian man with a big bag of groceries. Oblivious to those around him, he prepared and ate several salads and fruit dishes, carefully weighing them and then entering them into a spreadsheet on his laptop as he ate, afterwards spending ten minutes loudly flossing his teeth. This seemed to me to be a strange thing to do, and by their strained glances at him, I think some of the speakers were debating whether or not they were being insulted. Later I discovered that he believed that in order to best achieve longevity one should adopt a paleolithic diet, since that’s what our bodies are presumably evolved to survive on.

Meeting José Luis Cordeiro, the host of TransVision 2005 (to be held in Caracas, Venezuela) was rewarding as well. Cordeiro has written extensively on both transhumanism and the socio-political future of Latin America, but even though his books sell well from Mexico southward, he’s had little luck reaching the North American market — as he opined in a seminar on writing transhumanist books (moderated by Simon Smith) information flows out of America, but rarely in. I believe that Cordeiro is exactly what transhumanism needs — an optimist (but a realist) with a technical background, and with a sense of humor and the charisma required to present far-out ideas to the general public.

All this said, I really must encourage readers to take advantage of events like TransVision when they happen in your area. Don’t underestimate the value of getting to meet world class thinkers — even the ones you disagree with — in person. Don’t underestimate the value of introducing yourself into dialogs you might otherwise not be able to have. As much as I didn’t think much of a few of the presenters, the ones I disagreed with the most are also the ones that got me thinking aggressively about where humanity is going and how we should take it there.

Finally, if I could say one thing to transhumanists in general, it is to follow Steve Mann and Stelarc’s example and make it real. Don’t just talk about far future fantasies. Taking the first step may not be as fantastical as masturbating over the year 3000, but it’s the only way that we can force transhuman evolution without being restricted by governments and corporations, who will act in the best interests of nationalism and capitalism, rather than humanity’s future. While it’s true that we’ll see the occasional Mr. Hyde as a result, I call out to Bruce Banner: it’s time to irradiate yourself.

Shannon Larratt

BME.com

BME/News and Modblog highlight only a small fraction of what BME has to offer. Take our free tour and subscribe to BME for access to over 3 million body modification related photos, videos, and stories.

BME/News and Modblog highlight only a small fraction of what BME has to offer. Take our free tour and subscribe to BME for access to over 3 million body modification related photos, videos, and stories.