Just for the record, I do not claim, nor have I ever claimed that I single-handedly started the modern body piercing movement. I was fortunate to be in the right place at the right time to focus and channel forces that were already at work in the world. Would the movement have happened without me? Possibly, but if it had, it probably wouldn’t look quite like it does today.

Body piercing has been around for countless millennia. However, in the early 1970’s it was practiced, in the Western world at least, largely by a handful of widely dispersed and closeted hardcore fetishists. At that point in my life I never really thought that there might be a lot of other people in the world who found piercing as erotic as I did.

In 1973, my first year in Los Angeles, I was pretty much immersed in Primal Therapy. I rented a small apartment in West Hollywood a short walk from the Primal Institute and kept pretty much to the neighborhood.

Towards the end of the year, a fellow patient named Diane told me about a small two-bedroom house that was for rent about a block away. I had seen it often enough on walks around the neighborhood. It dated from the teens when West Hollywood — then called Sherman — had been a whistle stop on the railroad between Los Angeles and Santa Monica. Aside from its ramshackle condition and the Christmas tree dying in a pot by the front steps, its most memorable feature was a concrete shrine in the front yard where a votive candle burned day and night to the Virgin Mary.

For decades an elderly Italian woman had occupied the house. I don’t recall if she died or had been put into a home, but the property had been sold. An eccentric old couple, Velma and Carl Henning were managing it. Mrs. Henning looked like Ma Kettle and was so stingy she would scrounge through the supermarket dumpster for food. Her husband was an old Nazi with a handlebar moustache who had migrated to the States after the war. While he may have left the vaterland behind, his racist viewpoints were still as fresh as ever, and he was only too happy to share them whether one was interested or not.

Once they took over, the Hennings made some changes to the property. They cleaned up the house and demolished the shrine in the front yard, leaving a pile of concrete rubble. A sheet of plywood was laid over the rotting boards on the front porch to keep people from falling through. Always looking for ways to make a little extra money, Mrs. Henning rented yard space next to the house to a hippie couple to park their old school bus home. Arrangements had been made for them to use the toilet, which was just inside the back door.

The old West Hollywood house shortly before it’s demolition.

|

Rent on the house was little more than I was paying for my tiny apartment, so I signed a lease on it and moved in. There was a certain squalid charm about the place, but there was much about it that made living there a challenge. Chief among its shortcomings was a total lack of insulation or heat. One always thinks of Southern California as a land of eternal warmth and sunshine, but my first winter in the old house shattered that illusion.

West Hollywood at the time was still unincorporated, but the community was already beginning to exhibit the signs of change that, in a few short years, would turn it into the cold, impersonal city it has become today. Many small charming homes that dotted the township were being torn down and replaced by ugly apartment buildings.

Diane and I took great pleasure in rummaging through the abandoned old homes before they were torn down. Frequently we’d return home with odds and ends and, occasionally, useful junk. Rifling through the trash piles at construction sites I scrounged enough insulation to keep some of the cold out of my house.

I had a large back yard with a rundown shed — once possibly a garage for a Model A — and a huge avocado tree that bore wonderful fruit in summer assuming the squirrels didn’t ruin it first. There was lots of space for a garden, and Diane and I attempted, with limited success, to grow a variety of vegetables and flowers. Not only was the soil poor and the snails and slugs abundant, but the yard was something of a cross between a dump and an archeological dig. One could scarcely turn a shovel of earth that didn’t contain some bit of junk, mostly old bottles and broken crockery.

Amongst the debris was an old enameled cast iron toilet tank. Possessed by some perverse ingenuity I turned it into a small wood burning stove, attaching a stove pipe which I ran outside through one of the living room windows. Fueled with wood scraps from construction sites, it provided a source of free heat. By some miracle I didn’t asphyxiate myself. The first time I built a fire in the stove I had to run for cover. As the cast iron heated up and expanded, bits of enamel began to fly like shrapnel.

The necessity to earn an income encouraged me to seek employment. My experience in picture framing lead to a job with a snooty frame shop in West Hollywood. Among their clientele were a number of well-known museums and celebrity artists. While the occasional treasure passed through our hands, most of what we handled was high priced crap masquerading as art. I realized that this was not a profession I wished to pursue as a lifetime career. But what did I want to do? I remember thinking at the time I’d like to have a profession where I could use my hands and what I worked with would be small and fit into them. I also thought it would be wonderful if it had a sexual dimension as well. Little did I realize what was soon to materialize in my life.

Diane came up with the idea that we should enroll in court reporting school. After all, it was a well paying profession with great job security. There likely would be a demand for court reporters well into the future.

So we signed up and started learning the fundamentals of stenotype. It didn’t take Diane long to lose interest and drop out. I stuck with it for almost a year, reaching a level where I could take about 120 words a minute and type up a transcript at about 100 words a minute. The beginning months had been filled transcribing innocuous clerical material along the lines of, “Dear Mr. Smith: Please send me ten cases of tea.” What kept me intrigued as long as it did was the very weirdness of stenotype itself — I remember seeing a license plate bearing the letters TPUBGU; in stenotype that spells, “fuck you.” But that could hold my interest just so long. When the teacher began dictating actual court material I realized just how deadly boring the life of a court reporter could be. I doubt many of them get to take down juicy Perry Mason cases.

But my stint at court reporting school was not a total loss. We were required to take and pass a comprehensive class in English grammar and punctuation. The class was well taught and unlike the boring classes I’d suffered through in high school, actually made sense. Little did I realize that it wouldn’t be long before what I’d learned would come in handy when I started a magazine about piercing.

For the first year of so, most of the friends I made were people from the Institute. The main exception was my friend Rod from Denver. He had been married for some years and had several grown children. Approaching middle age, he was no longer willing to deny the gay side of his nature. The year before I moved to LA, he packed a few essentials, said goodbye to wife and family, climbed on his Harley, and headed for California settling down in Los Angeles with a succession of male lovers. Soon after arriving he took a job as a bus driver.

I’ve often marveled at that thing we call fate. Is there really such a thing, and if not, how do we explain those amazing coincidences that happen in our lives?

Rod’s regular bus route was between Hollywood and downtown Los Angeles. One day an amiable long-haired gentleman boarded his bus, and taking a seat near the driver, struck up a conversation. The man’s name was Tom and he worked as a librarian at the downtown public library. Tom became a regular commuter on Rod’s bus, and one morning as they were chatting en route to downtown, a man with a pierced ear boarded the bus. The conversation turned to the subject of piercing and Rod said, “I have a friend with pierced nipples,” to which Tom replied, “I’d like to meet him.”

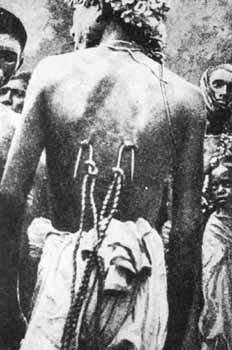

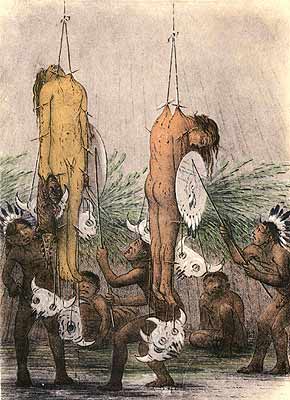

I must confess that I secretly hoped that Tom would be a sexy hunk, but instead I met a rather plain, round-faced, slightly heavy set man in need of dental work. Whatever he lacked in looks was offset, to some extent, by a sunny disposition and a passion for piercing. He shared with me a collection of letters and photographs from a number of fellow enthusiasts who, at the time, were unknown to me. Among these was one “Rollie Loomis” who would soon become known as Fakir Musafar. The photographs of him that Tom showed me were truly awesome. I’d never seen anything like them. They made me aware that there were many more piercing possibilities than I had ever dreamed of.

Another of Tom’s correspondents was a man named Doug Malloy. He was supposedly some well-traveled expert on the subject of piercing. Since he lived locally Tom arranged for us to get together one evening so I could meet him. We were to rendezvous at the public library where Tom worked and then go out for dinner.

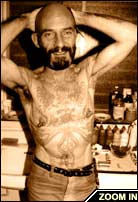

Doug Malloy (left) and Alan Oversby aka Mr. Sebastian (right).

|

Doug arrived with a guest, a man named Alan Oversby. Over dinner I learned that Doug had recently written a short autobiographical account of his piercing exploits called The Adventures of a Piercing Freak. A somewhat sleazy fetish publisher had purchased it and to add visual interest had included a number of photographs bearing no relation to the text.

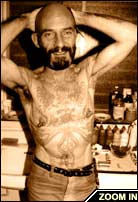

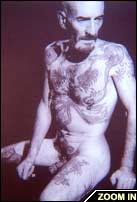

Alan showing his art work.

|

Alan, it turned out, was from England where he worked as a tattoo artist who also did some body piercing. His professional name was “Mr. Sebastian.” Doug had corresponded with him, and Alan had shown a great deal of interest in learning more about the art and technical aspects of piercing. Using the money from the sale of his book, Doug had paid for Alan to come to the States.

It was a pleasant evening. We parted company, and I heard nothing further from either Doug or Alan.

During my Primal Therapy experience I became a very good friend with another patient named Jim. After a couple of years at the Institute, he decided it was time to get on with his life and moved to San Francisco. Periodically I would fly up to spend a weekend with him. He would show me the sights. Sometimes we’d smoke a little grass and hit the gay nightspots.

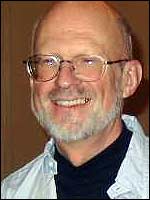

Eric. In a way he started it all.

On one of these outings a guy named Eric came on to me. We spent some time together, and though the chemistry wasn’t exactly ideal, we started to see each other on a regular basis, sometimes in San Francisco, sometimes in LA. Eric was very turned on by my nipple piercings and called me to see if I would pierce his nipples the next time he came to LA. While I was certainly willing, I realized that my pushpin-and-wine-bottle-cork method left a lot of room for improvement. I also knew from my brief meeting with Doug that earrings were not the right jewelry for the job. Since a more knowledgeable source was close by, it made sense to see if I could get a little guidance.

I called Tom and, after explaining the situation, asked if he would give me Doug’s phone number. This he did, and I gave Doug a call, asking if he would be willing to share some of his piercing techniques with me and tell me where I might be able to purchase appropriate jewelry. He couldn’t have been more accommodating. The techniques he’d developed over the years were at my disposal. All I needed to do was let him know when Eric would be in town and we’d set something up.

As for jewelry there weren’t many choices. Doug knew of a jeweler in San Diego who would make gold rings, but the guy was asking $200 apiece for them. This was much more than I was willing to pay. Having taken several jewelry making classes in New York, including one for professionals, I had a pretty good idea what it would take to make a pair of nipple rings, and $400 was way out of line. As I got to thinking about it, I realized that for a fraction of that amount of money I could buy the raw materials and the necessary tools as well.

The nipple retainer, my very first body piercing jewelry design.

|

Doug and I had several discussions about the best kind of jewelry to use for new nipple piercings. There was some question whether they would heal better with a curved ring or something that was straight. In the end we decided that maybe something straight would be the better choice. With that in mind I set out to design something appropriate. Thus came into being my first pieces of body piercing jewelry. I called them “nipple retainers.”

Consulting the Yellow Pages I discovered a lapidary shop in nearby Hollywood. They were able to supply enough gold wire for the project and the various tools I needed, all for under $50.

|

Early tools of the trade. The ear piercer was eventually consigned to history, but Pennington forceps are now a piercing staple.

|

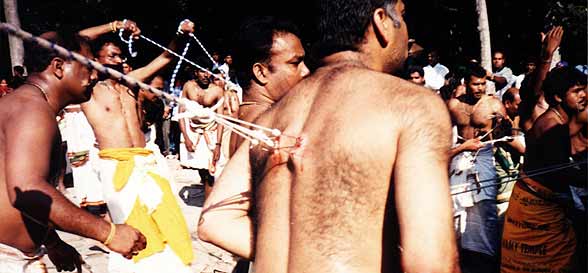

Once the jewelry was made, Eric arranged to come down to LA for the piercing. We set up a time for Doug to come over and supervise. He brought his “kit” of implements. These included a pair of Pennington forceps, now an industry standard but at that time something pretty exotic. There was also an assortment of heavy gauge hypodermic needles, the kind used on livestock, and what in the 1950’s had no doubt been a state-of-the-art ear-piercing gun. This latter contraption consisted of plunger on the end of which was a removable needle about 3/4” long. Over the needle fit a short metal sleeve called a canula. By pressing firmly on the plunger, the needle and canula were forced through the tissue and a fork-like stop on the opposite side. Once the pressure was released, a spring would retract the plunger pulling back the needle and, hopefully, leaving the canula in the tissue. The jewelry could then be inserted by butting it against the end of the canula and following it through the piercing.

My mother worked for twenty five years for an eye doctor, so I had gained some rudimentary awareness that sterilization of the instruments was in order. Fortunately I had a pressure cooker which I usually used for cooking, but it worked just fine as a stand-in for an autoclave. These were the days before AIDS, so we gave no thought to latex gloves. After all, even dentists and tattooists worked without them. Only doctors doing surgery wore them. We assumed that as long as our hands got a thorough washing, that was enough.

|

The piercing process may have been crude, but at least we got the jewelry insertion principle right.

|

Except for using the ear-piercing gun as part of the procedure, the piercing technique itself was much like it is today. The nipple was first cleaned. Since surgeons were using it in surgery, we had elected to use Betadine instead of alcohol. Next a dot was made on either side of the nipple where we wanted the opening of the piercing to be. A rubber band was wrapped several times around the handle of the Pennington forceps and adjusted for the right grip. The nipple was clamped into the forceps and the marks aligned in the same place on either side. Once the ear-piercing gun was placed in position, the needle and canula were forced through the nipple. As the needle retracted, the canula was left in place. After laying aside the gun, the forceps were removed and the jewelry inserted.

Though still crude by today’s standards, Doug’s technique worked amazingly well, and the piercing went smoothly. Eric returned to San Francisco happy.

Soon afterward Doug called me up and asked me to have lunch with him. He picked me up in his sports car, and we went to the Red Room, a little Swedish café in West Hollywood not far from the frame shop where I worked. Over lunch the conversation naturally turned to the subject of piercing. To my surprise Doug said he thought I should start a piercing business. I already knew how to make the jewelry. All that remained was for him to teach me what he knew about the various piercings and his techniques for doing them. I could start out working part time from home, and he would share his private mailing list of enthusiasts around the world as the basis for mail order. When I pointed out that I lacked the capital to launch such an endeavor, he told me he was prepared to lend me whatever it would take. He firmly believed that a need existed for such a business and told me that from the moment he first laid eyes on me at the library, he’d known that we were destined to do something together. This was it.

Presented with such a generous offer and the possibility of creating a career for myself doing something I loved was not something I could pass up. I said yes.

Next: In The Beginning There Was Gauntlet

| Jim Ward is is one of the cofounders of body piercing as a public phenomena in his role both as owner of the original piercing studio Gauntlet and the original body modification magazine PFIQ, both long before BME staff had even entered highschool. He currently works as a designer in Calfornia where he lives with his partner.

Copyright © 2003 BMEzine.com LLC. Requests to publish full, edited, or shortened versions must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published November 11th, 2003 by BMEzine.com LLC in Tweed, Ontario, Canada

|

|