Here’s Sui Otoko (see more in the Spring’s Sex Slave Milk bonus gallery in BME/HARD) playing with some very muscular beetles. Or should I say they’re playing with her? Working for her? Anyway, click to uncensor:

Author Archives: Shannon Larratt

Post navigation

Mark Mask in Brasil

Photo: George Zix, Sao Paulo.

(I’m continuing to test things; more later today).

Which side will win?

I’m continuing to fiddle with my anti-scraping script… Maybe it’ll work this time. If not, enjoy Jusn‘s Star Wars tattoo (on vacation in Hawaii) by Jim Valavanis at Highway Tattoo in Sonoma, CA.

BME Newsfeed for Sep 7, 2006

- 2006-09-07: MI: Some students opt for ‘ink’ [by deadly pale]

- 2006-09-07: CA: Jake La Botz debuts album at tattoo parlors across U.S. [by deadly pale]

- 2006-09-07: TX: More Americans are inking up but can tattoos cost you a job? [by deadly pale]

- 2006-09-07: USA: Jake La Botz and ‘Tattoo across America’ Tour [by deadly pale]

- 2006-09-07: UK: Tattooist tried to torch rival’s home [by rebekah]

Please note that links may expire. IAM members, please help out by submitting stories!

“Queer Trades To Live”

In 1901 The San Francisco Chronicle published an article (later reprinted August 25, 1901 in The Washington Post) discussing unusual jobs that people (who they called “celebrities”) could make a decent living at — this included widow-consoler, tail-biter (someone who amputates the tails off of dogs), prayer-seller, and tattoo artist. Here’s what they wrote about the option of becoming a tattoo artist — the profession hasn’t changed much, other than the fact that tattooing is no longer painless* and the pervasiveness of blood borne pathogens requires modern artists to focus more strongly on cross-contamination.

Oh yeah, and most of the time these days, tattoo artists are not called “the professor”. Well, if I ever start tattooing again, I’m going to try and re-popularize that nomenclature.

A Professional Tattoo Man.

He works in a little hole in the wall between a saloon and a shooting gallery. The front is plastered over with photographs showing some of his best work and with designs for the human body, each having its accompanying price. Plain initials he will put on your leg or arm for 25 cents, and he will add a decorative frill for a little more. An American flag costs $1.25 and a full spread eagle twice that sum. He will take the photograph of any friend and transfer a copy to the skin of a customer for $3.50, the process taking a half hour.

The professor does not work with the old-fashioned sailor needle, but with an electrical machine that looks and acts like the fiendish “buzzer” of a dentist. At the point is a battery of half a dozen tiny needles, which shoot like lightning back and forth when the power is applied, each leaving a tiny microscopic prick. When he has a customer the professor takes a stencil, marks out the design, and then follows the line with his buzzer, dipping it in the proper ink as he goes. This is for customers who patronize him openly in his office. For those who avoid publicity and want the work done at home he sends his Japanese assistant, who works by hand, after the old-fashioned method.

“The tattooing is perfectly harmless and is not painful at the time,” he says. “It swells and inflames afterward, but little more than an ordinary pin prick. We generally tattoo the ladies on the shoulder just below where a low-neck dress comes. I have tattooed lots of the toniest people in town; in fact, they are my best customers. People used to have a prejudice against tattooing; they are getting over that.“

I love the last paragraph — you could read the exact same thing (well, other than “toniest” which I had to look up to know what it meant) in a tattoo interview in 2006. It’s funny how much things stay the same, but through the eyes of the moment they always feel so fresh. Oh, and to put the pricing into context, $3.50 an hour in 1901 dollars is about $80-$150 an hour in today’s dollars.

* Until 1914, tattoo ink was often mixed with cocaine to make the process painless.

DIY Branding

Now, before you slag Todd for using found-object tools for branding, I’d like to state for the record that I have brands that are now about 15 years old, done with pieces of a tin can, and they’re as well defined and raised and even as anything I’ve seen done using more widely accepted tools.

Oh, and I’m not sure if I’ve accidentally reposted some things in today’s update. My apologies if that’s the case.

Three Artist Tattoo Collaboration

Katie sends in this three artist rib panel tattoo by Erich D., Anji Marth, and Reed at HPP Ink in Eugene, OR. Click through for a second picture if you’d like.

Raygun Tattoo

I don’t know if it beats out my favorite gun tattoo (Andyroo’s blackwork gun), but James‘s raygun is definitely a close contender. It was done by Sol Good in Seattle, WA.

Other gun tattoos on ModBlog: Robin, Ass Shots, and Six-Shooters.

Nice stretched lobe photo

I just thought this photo from candycanegirl was really nice:

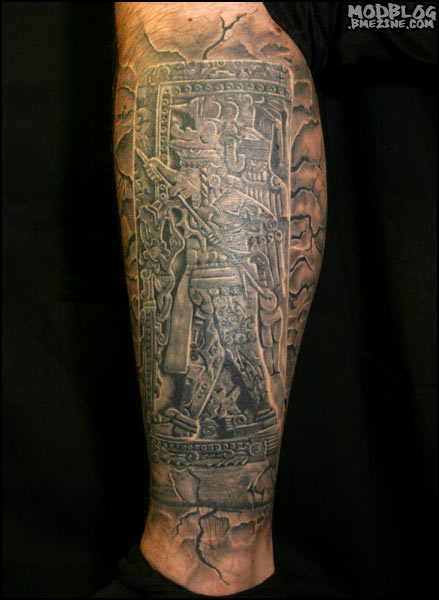

Tattooed Mayan

This tattoo, done in Russia (I’m sorry, I don’t know the artist’s name), is of a tattooed Mayan doing a bloodletting tongue piercing ceremony…