Our masters (the spirits) keep a zealous watch over us, and woe betide us afterwards if we do not satisfy them! We cannot quit it; we cannot cease to practise shamanic rites.

Randomly ask any amputee today about the nature of their “disfigurement” (ignoring all of the social idiums on couth), and expect one of several primary answers — assuming you haven’t pissed them off or trodden on some painful part of their life better left alone. Our first hypothetical example: A legless man in a wheelchair — mid 50’s — perhaps he lost them on a mine in Vietnam, his “mobility and vitality” stolen from him in his youth by the “enemy”... non-consentually. Next, an older man (yes, women can be amputees too) missing a forearm and a hand... his whole life haunted by the feeling that with both hands he is incomplete as a person until that appendage is sacrificed. Consumed with a deep, unnameable need to remove part of the anatomy considered essential — perhaps an “accident” with a Skilsaw — and now he is content... an indescribable inner part of himself somehow satiated. For our third example we turn back the hands of time (no pun intended)... about 30,000 years! The place is a dark cave in Paleolithic Europe. With the entire clan in attendance — spellbound — an elder shaman severs a digit from his hand. Does he hate himself? No. Does he have issues? No. The primitive mind and developing psyche of humanity is consumed wih offerings of magic, sacrifice, the spirit-world, and the animal kingdom, upon which he depends for survival.

New evidence has unearthed (in the same caves that housed the amputee art): a thumb phalanx, and other human finger bones found in association with shell pendants, stone beads, the perforated teeth of an Arctic fox, a Mammoth tusk boomerang (the oldest boomerang ever found), and other ritual objects. They date to more than 30,000 years ago. Pawel Valde-Nowak, the scientist who excavated the site believes that this proves that “fingers were amputated in a ceremonial context” and that amputee art gives “depictions of hands (with missing digits) a very particular symbolic meaning”. Even with our imaginary time-travel, early language, grammar, and syntax prevent the modern mind (if we could ask) from communication with the shaman in the cave. “Why?” we might inquire, yet the ritual context of this ancient amputation lets the scientific mind extrapolate, respect, and appreciate the ceremonial, even religious rite associated with the ancient amputation.

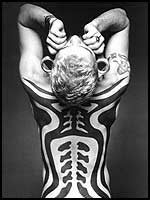

Amputation, drugs, religion, meditation or ritualized body adornment are means by which we may glimpse the divine, or, that which is greater than the sum of our “parts”. These vehicles of transcendental experience are doorways to an ancient state of mind. To borrow a quote from my book, “the ways by which we find release and transcendence as a species are varied, indeed.”

Blake Perlingieri is a body piercer of fifteen years, a museum curator, and a self-educated anthropologist. He is the author of A Brief History of the Evolution of Body Adornment in Western Culture and can be found online (and offline) at nomadmuseum.com. Copyright © 2003 BMEZINE.COM. Requests to republish must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published December 17th, 2003 by BMEZINE.COM in Tweed, Ontario, Canada. View all BME Cultural Corner columns | Return to BME/News |