by Frederick G. Volpicelli, CCP

In 1931, Tolkien wrote an essay about the somewhat peculiar hobby of devising private languages. He called it “A Secret Vice”. But in Tolkien’s case, the “vice” can hardly be called secret anymore.

What, really, is going on inside the head of a man who all his life is toying with enormous linguistic constructions, entire languages that have never existed outside his own notes? One thing that was important to Tolkien was that languages should be beautiful. Their sound should be pleasing. Tolkien tasted languages, and his taste was finely tuned. Latin, Spanish and Gothic were pleasing. Greek was great. Italian was wonderful. But French, often hailed as a beautiful language, gave him little pleasure, but heaven itself was called Welsh. He stated that the Elvish tongues were “intended to be definitely of a European kind in style and structure and to be specially pleasant.” While World War I was still raging, Tolkien’s linguistic constructions definitely became elvish languages. In 1916 he wrote that he had been working on his “nonsense fairy language — to its improvement. I often long to work at it and don’t let myself ’cause though I love it so it does seem such a mad hobby!” Mad or not, he was to give in to his longing and keep working on this hobby throughout his life. Exactly at this point, in 1916, while Tolkien was in the hospital having survived the Battle of Somme, the very first parts of his “mythology for England” were written — fragments of what would one day become the Silmarillion. At the same time, he wrote his first Elvish word-lists. One thing triggered the other: “The making of language and mythology are related functions,” he observed in A Secret Vice. “Your language construction will breed a mythology” Or again in a letter written many years later, shortly after the publication of Lord of the Rings: “The invention of languages is the foundation. The ‘stories’ were made rather to provide a world for the languages than the reverse. To me a name comes first and the story follows. Lord of the Rings is to me...largely an essay in ‘linguistic aesthetic’, as I sometimes say to people who ask me ‘what is it all about?’” Few people took this explanation seriously. “Nobody believes me when I say that my long book is an attempt to create a world in which a form of language agreeable to my personal aesthetic might seem real,” Tolkien complained. “But it is true.” The years passed by and the stories of the Silmarillion evolved, but it seems that the relevance of the original dictionaries soon dwindled: Frequent revisions inevitably rendered them obsolete. In the second half of the thirties, however, Tolkien made a list of some seven hundred Primitive Elvish “stems” and some of their derivatives in later languages. It was apparently this list, the so-called Etymologies, he was referring to when he started to write The Lord of the Rings.

Throughout his life he kept revising, revising, revising. In the words of his son, “The linguistic histories were...invented by an inventor, who was free to change these histories as he was free to change the story of the world in which they took place, and he did so abundantly... Moreover, the alterations in the history were not confined to features of ‘interior’ linguistic development: the ‘exterior’ conception of the languages and their relations underwent change, even profound change.”

How, then, do Tolkien’s languages fare today, when a quarter of a century has passed? Some of us have embarked on the study of Elvish, perhaps with somewhat the same attitude as people enjoying a well-made crossword puzzle: The very fact that no real Elvish grammars written by Tolkien have been published makes it a fascinating challenge to “break the code”. Many simply enjoy the Elvish languages as one might enjoy music, as elaborate and (according to the taste of many) gloriously successful experiments in euphony. During my 40-year study I never actually tried to pronounce Elvish. It wasn�t until the movies were released that the music of Tolkien�s language came through for me. For those of you who are interested you can find an online Elvish Pronunciation Guide [dcs.ed.ac.uk].

To further my ability to deal with Elvish I took a college course in phonetics. (My NYU advisor had fits with me. I was a math major, taking a minor in English Literature, with Greek and Roman mythology, art history, and phonetics as electives). With a solid background in phonetics I was able to transcribe English into Elvish. You first break down the English into pure phonetic constructs. There is a whole separate compendium of characters to describe how words are actually pronounced (far past what�s in the dictionary). The beauty of phonetics is that the same constructs apply basically to all languages. Tolkien used these sale constructs to build his elvish language. There are direct correlations between the constructs and the written elvish letters. So with a lot of study I was able to convert words into elvish script. Now back then, of course, it was all done by hand and mind. A long tedious process. I used to hand letter custom t-shirts for people as a way to pay the bills (somewhere along the way I took up the study of calligraphy). Fueled with copious amounts of drugs I got through college, picked up a Master�s degree in Computer Science, and started teaching. I was a High school math teacher, Assistant Professor of Computer Science, Visiting Lecturer, and now a network and Internet consultant. Along this 35-year odyssey, computers developed, and fonts came into being (it may not seem so, but True Type computer fonts are a very recent development).

The artical title at the top of the page, “ELVISH SPOKEN HERE,” is transcribed just above it into the Tengwar cursive form of Elvish. The intermediate phonetic construct is written “jRrdT 8qzY5$ 96RO”. The construct is then converted to the correct Elvish font. The form of Elvish as created by Tolkein is known as Tengwar. This is a family of written languages belonging to the elves. The common style is called Sindarin and is the language of the Grey-Elves (i.e. Rivendell), another style is Quenya belonging to the “High-Elves”. There are numerous written variations, with some in the cursive style above and some in a more Runic style (as is the Cirth language of the Dwarves). Frederick G. Volpicelli, CCP

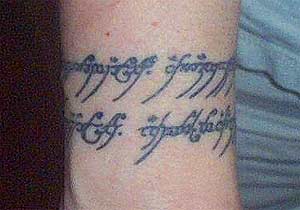

What follows is the phrase “Elvish Spoken Here” transcribed into Tengwar in different styles.

|

This brings us over to the technique used by Tolkien in devising his linguistic creations. How was it done? Christopher Tolkien, his son, describes his father’s strategy as a language-maker in one formidable sentence: “He did not, after all, ‘invent’ new words and names arbitrarily: in principle, he devised from within the historical structure, proceeding from the ‘bases’ or primitive stems, adding suffix or prefix or forming compounds, deciding (or, as he would have said, ‘finding out’) when the word came into the language, following it through the regular changes in form that it would thus have undergone, and observing the possibilities of formal or semantic influence from other words in the course of its history.” The result: “Such a word would then exist for him, and he would know it.”

This brings us over to the technique used by Tolkien in devising his linguistic creations. How was it done? Christopher Tolkien, his son, describes his father’s strategy as a language-maker in one formidable sentence: “He did not, after all, ‘invent’ new words and names arbitrarily: in principle, he devised from within the historical structure, proceeding from the ‘bases’ or primitive stems, adding suffix or prefix or forming compounds, deciding (or, as he would have said, ‘finding out’) when the word came into the language, following it through the regular changes in form that it would thus have undergone, and observing the possibilities of formal or semantic influence from other words in the course of its history.” The result: “Such a word would then exist for him, and he would know it.” Sindarin is a good example of changed ideas about the outer history of the languages. The scenario set out in the appendices to Lord of the Rings is that this is the language of the Sindar, the Grey-elves — the Elves that came to Beleriand from Cuiviénen, but did not go over the sea to Valinor. But in Tolkien’s pre-Lord of the Rings notes, Sindarin is called Noldorin, and before that Gnomish, for this was the language of the Noldor or “Gnomes”, the “Wise Elves”. It was developed in Valinor, while Quenya in the former scenario was the language of the Lindar, the first of the three clans of the Eldar (to complicate matters even further, the Lindar were later renamed and became the Vanyar, while Lindar became a name of the third clan, the Teleri). But then Tolkien must have realized that the Elves, immortal and all, would hardly develop radically different languages when they lived side by side in Valinor. So according to the revised scenario, both the Vanyar and the Noldor spoke Quenya with just minor dialectal differences, while the “Noldorin” language that Tolkien had already made was simply re-christened Sindarin, transferred from Valinor to Middle-earth and relocated to the mouths of the Grey-elves there. It was, of course, far more plausible that they had developed a language very different from Quenya, having been separated from their kin in Valinor for thousands of years. Christopher Tolkien comments, “So far-reaching was this reformation that the pre-existent linguistic structures themselves were moved into new historical relations and given new names”. The various “flavors” of Elvish in body face above will later connect directly to various writing styles Tolkien invented. It is interesting to note that as he invented these languages and allowed them to age and morph together he continually left the original constructs alone. His language, therefore, has dialects spanning hundreds of years.

Sindarin is a good example of changed ideas about the outer history of the languages. The scenario set out in the appendices to Lord of the Rings is that this is the language of the Sindar, the Grey-elves — the Elves that came to Beleriand from Cuiviénen, but did not go over the sea to Valinor. But in Tolkien’s pre-Lord of the Rings notes, Sindarin is called Noldorin, and before that Gnomish, for this was the language of the Noldor or “Gnomes”, the “Wise Elves”. It was developed in Valinor, while Quenya in the former scenario was the language of the Lindar, the first of the three clans of the Eldar (to complicate matters even further, the Lindar were later renamed and became the Vanyar, while Lindar became a name of the third clan, the Teleri). But then Tolkien must have realized that the Elves, immortal and all, would hardly develop radically different languages when they lived side by side in Valinor. So according to the revised scenario, both the Vanyar and the Noldor spoke Quenya with just minor dialectal differences, while the “Noldorin” language that Tolkien had already made was simply re-christened Sindarin, transferred from Valinor to Middle-earth and relocated to the mouths of the Grey-elves there. It was, of course, far more plausible that they had developed a language very different from Quenya, having been separated from their kin in Valinor for thousands of years. Christopher Tolkien comments, “So far-reaching was this reformation that the pre-existent linguistic structures themselves were moved into new historical relations and given new names”. The various “flavors” of Elvish in body face above will later connect directly to various writing styles Tolkien invented. It is interesting to note that as he invented these languages and allowed them to age and morph together he continually left the original constructs alone. His language, therefore, has dialects spanning hundreds of years. My own story started 40 years ago. I personally made a serious study of Elvish from 1964-1968 while attending the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University. It was a very complex game that allowed me to get lost in the Appendices of Lord of the Rings while surviving Calculus and Physics. In 1966 I switched from pure math to the then very new study of computers and proceeded to absorb my first computer language, Fortran II. Quickly added was Fortran IV (later to morph into Fortran 77 with BASIC as a subset), COBOL, SNOBOL, ALGOL, LISP, PL/1, and, of course, the very elemental assembly language (first for the Control Data 6600 mainframe, then 6502 processors). I don�t think I realized it then, but the study of elvish constructs prepared me for my initial forays into computer language. Tolkien�s language was perfectly created, few holes, strict rules, and logically bound. Just like computer languages (which didn�t exist when Tolkien invented Elvish).

My own story started 40 years ago. I personally made a serious study of Elvish from 1964-1968 while attending the Courant Institute of Mathematical Sciences at New York University. It was a very complex game that allowed me to get lost in the Appendices of Lord of the Rings while surviving Calculus and Physics. In 1966 I switched from pure math to the then very new study of computers and proceeded to absorb my first computer language, Fortran II. Quickly added was Fortran IV (later to morph into Fortran 77 with BASIC as a subset), COBOL, SNOBOL, ALGOL, LISP, PL/1, and, of course, the very elemental assembly language (first for the Control Data 6600 mainframe, then 6502 processors). I don�t think I realized it then, but the study of elvish constructs prepared me for my initial forays into computer language. Tolkien�s language was perfectly created, few holes, strict rules, and logically bound. Just like computer languages (which didn�t exist when Tolkien invented Elvish). Turns out that there a lot of other fanatics like myself out there! Computer tools have been developed to transcribe the root English to phonetic constructs. True Type Elvish Fonts are developed. Photoshop provides the art space. Now I can transcribe rather quickly. Late last year, with the movies being so popular, I offered BME members a free transcription of anything they want. I create a hi-res JPG in one of the many elvish fonts available.

Turns out that there a lot of other fanatics like myself out there! Computer tools have been developed to transcribe the root English to phonetic constructs. True Type Elvish Fonts are developed. Photoshop provides the art space. Now I can transcribe rather quickly. Late last year, with the movies being so popular, I offered BME members a free transcription of anything they want. I create a hi-res JPG in one of the many elvish fonts available.