A POSTCARD ARTICLE FROM ECUADOR

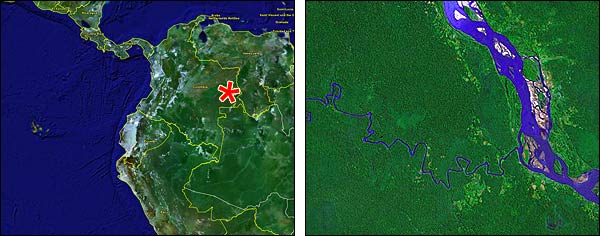

“Why do rich countries come here? People from the richest and most populated countries come to the poorest to take its resources, to take and negotiate, to live their life better and leave us even poorer. But we are richer than they because we have the resources and the forest, and our calm life is better than their life in the city. We must all be concerned because this is the heart of the world and here we can breathe... So we as Huaorani, we ask those city people: Why do you want oil? We don’t want oil.”Hi Shannon, Being a biologist who specializes in tropical species of reptiles and amphibians, I have been really lucky to get to travel a lot in the past few years — more recently to some of the less frequently traveled areas of South America. The most recent trip I have moved to Ecuador to work on conservation of amphibians. The first month, I lived up North in a national park called Yasuní. It is very close to the Ecuador and Colombian border sandwiched between the Napo and Tiputini rivers.

Yasuní National Park

We went to the nearest market looking to see if the ‘Huas’ were still hunting monkeys from the monkey plot, as well as looking if there were any monkey products or meat for sale. On the way we met an older man who looked some sixty years old or so but was probably no older than forty. He was wearing just a pair of white underwear (what we affectionately call ‘tightey-whiteys’ in the US), and had long black flowing hair, large stretched lobes, and his feet were oddly shaped. They were turned inwards and he had an enormous arch in them. I was later told that this is one of the ways to tell someone who hunts and harvests things from trees. It was fascinating how the body would adapt to that type of work. This man needed a ride to a neighboring town, and I was all too happy to have him along. The only problem was that he was of the generation which had not learned Spanish, so he spoke only Huaorani. By using gestures and the like, we were able to have a slight conversation during the hour ride. It was right about that time that I had also been reading Savages by Joe Kane. It had given me a good look into the life of the Huaorani. Their culture, from what I had learned from the book and from what I had seen, was so very different from our own. They literally live day to day, hour to hour. If given a ration of rice to last them a week, they will probably eat it all that day. Kane describes them gorging themselves to the extent they can hardly move and just sleeping it off. Conversely, they can also go days and days without eating, but doing intense physical exercise, and be fine.

Huaorani Blowgun

As I had previously mentioned, and probably the only reason you are reading this, the older generations have large stretched lobes. The original piercing of the ears is done by taking a large spine from the trunk of a tree. Those spines are kept in the ears for some time, and they are stretched slowly using pieces of wood. As they get larger and larger, new disks of wood are placed in the ears. As the stretchings mature, they are left unadorned with the lobes hanging. The younger generations have not taken on the same adornments — most of them choose instead Nike shirts and things purchased from street vendors or passed along to them.

Click photos to zoom in

I have the utmost respect for these people, their culture, and their abilities. Sincerely,

Justin Yeager

Online presentation copyright © 2005 Shannon Larratt, Justin Yeager, and BMEzine.com. Photos courtesy of Justin Yeager. Requests to republish must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published online July 30th, 2005 by BMEZINE.COM in La Paz, BCS, Mexico. |