Carl Vadivella Belle

Kavadi Blog Interview

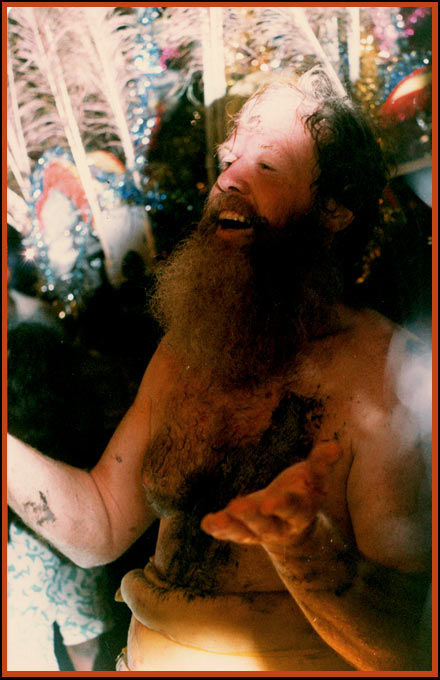

Searching for diverse kavadi and spear-related experiences around the world I came in contact with Carl Vadivella Belle, who lives in Australia. Carl first saw a Thaipusam in 1976 in Kuuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Impressed by this, Carl converted from non-practising Christian to Hindu, and in 1981 he experienced his first Thaipusam, and in 2007 his most recent. I was curious to know how a Western man could experience the whole ritual and recently had the opportunity to talk to him about it.

http://kavadinfo.blogspot.com/

E.K.: How did you take the first steps towards carrying a kavadi?

C.V.B.: I was posted to the Australian High Commission, Kuala Lumpur, in October 1976. At the time of my arrival in Malaysia, I had long broken with my own Christian upbringing, and had no religious beliefs. However, because my work entailed dealing with students, and because of the manner in which religion and ethnicity operated in Malaysia I soon discovered that if I were to understand anything about my students I would need to learn something about the major religious traditions of that country. As a consequence I undertook some studies into Islam, Buddhism, Taoism, Sikhism, and Hinduism. We also visited a large number of religious and cultural festivals. I first saw the major festival of Thaipusam at Batu Caves, Kuala Lumpur in January 1978, and was so overcome that I had to sit down; I felt that I would pass out. The reason was not the body piercings, but rather the intense vibrations I felt emanating from the devotees; it was totally unlike any other emotion I had ever experienced, and certainly different from anything in my own religious background. This was spirituality as pure ecstasy. Indeed, I commented to my wife, Wendy, that I could see myself engaging in this, but of course, later that day my “sceptical-scientific” Western background reasserted itself, and I dismissed my feelings as a psychological trick of the mind. However, I did follow a friend who took a kavadi in the Thaipusam festival of 1979, and again I felt overcome and strongly attracted to the ritual.

I returned to Australia in 1979, and felt culture shock. I felt that I had left for Australia prematurely, and that Malaysia held the answer to my queries. I had a number of psychic experiences after I returned to Australia, but I kept denying the validity of these experiences. The culmination came at a party I attended on 29 September 1979. I was talking to a group of scientists, who were enthusiasts for genetic engineering. I was horrified at the narrow world they envisaged, and the hatred or at least contempt for humanity which informed their arguments. Finally, one of these scientists turned to me, and stated “You are obviously speaking from a religious point of view. What religion are you?” Without time to think, I responded automatically, “I am a Hindu”, thus acknowledging for the first time, all that happened to me over the past twenty months.

That night I had a powerful vision. I saw waves of kavadi bearers at Batu Caves, humble in the face of the Divine, and I saw the arrogance of a particular strand of Western science, dismissive of fellow humans. As I pondered on this, I saw Lord Murugan, the God of Thaipusam appear in a brilliant blue light, and summon me to Batu Caves, and I knew I had been asked to bear a kavadi. I thus made a vow to take a kavadi on five occasions (2007 was my fifteenth kavadi!) and my first pilgrimage was in January 1981.

E.K.: Did you communicate with family and friends about this process?

C.V.B.: I obviously told my wife and children. My wife, Wendy (now Wendy Valli; we both took Hindu names) was supportive right from the beginning and has remained strongly so over all these years. I didn’t tell most people. I believe that religion is a private issue, and Hindus do not hold with aggressive conversions or in preaching to those who hold other views. However, the Australian press got hold of my appearance at Thaipusam in Malaysia and publicized this. My father (a real Christian) understood my motives, and my family were puzzled but basically accepting. But I did lose some friendships, and my participation in Thaipusam did damage my Australian Public Service career and ultimately forced me to leave the Public Service and to move from Canberra, the city in which I was based, to the more tolerant and accepting environment of South Australia. The sensationalist and irresponsible Australian press coverage, which continued over several kavadis, did not help in this process.

E.K.: Do you have a special diet or other restrictions before Thaipusam? How do these rituals affect your experience on the day of the main ritual?

C.V.B.: Those who take a kavadi must be in a state of ritual purity on Thaipusam day. This means that they must observe a range of restrictions for a set period, sometimes lasting up to 42 days before Thaipusam and for two days after Thaipusam when they undertake a special puja (prayer) which releases them from their restrictions. At the start of their “fasting”, devotees take a vow which means the following restrictions:

- A strictly vegetarian diet (no fish or eggs)

- Control of food intake (in general no more than one meal per day)

- Sleeping by yourself, on the floor (on a yellow cloth) in a clean environment

- Sexual abstinence

- No alcohol or nicotine

- No death within the immediate family for the past twelve months; if this has occurred you must postpone your kavadi

- Think only good thoughts, and refrain from bad language, anger, and entertainments which involve crudity, violence, or anti-social messages.

- A range of formal spiritual obligations.

This is a difficult process, but the idea is to step outside of daily routines to enter a form of “sacred” time; to live for a short time as a renunciate. At my first kavadi I fasted for 42 days, but now that I am a fulltime vegetarian I normally fast for thirty days prior to Thaipusam.

Fasting has a strange effect on your outlook. Hindus believe in three basic qualities or gunas which comprise the average human make-up. These are tamas (or darkness), rajas (the activating principle) and sattva (purity). In this age, the age of the Kali Yuga, (or age of destruction), the predominant quality is tamas. So the idea of fasting is to move the devotee from tamas through rajas to sattva in which the devotee will overcome pain and feel the sense and presence of the deity. Fasting reflects this transition. For the first few days of fasting many devotees feel confused, dazed, irritable, and generally at odds with the world. But after a few days, many feel a sense of energy, and see the world with a fresh clarity, and through a new perspective. The onset of the divine trance (arul) is the stage at which sattva arises, and in which pain is overcome. This is symbolized by the painless and bloodless insertion of vels (skewers) and hooks. This sequence has also been my own experience. The whole experience of fasting is part of the spiritual journey, and it essential that it be followed properly if the devotee is to gain the maximum benefit from his/her pilgrimage.

E.K.: Do you build the frame yourself?

C.V.B.: No. As I have to travel from Australia to Malaysia for Thaipusam, this would be impossible. Also I am not especially gifted at making things, so I cannot imagine a kavadi that I had constructed — it would be unique! I normally rent a pre-made kavadi from the temple where I start the most intense part of my pilgrimage.

E.K.: How much time does it take before you start walking and dancing?

C.V.B.: Normally, I go to the temple the night before I am due to take a kavadi. In the morning there are a number of rituals to be gone through, and this means that it is a couple of hours before we actually leave the temple to go to the Caves.

These include a trial trance the night before Thaipusam, the tying of the yellow thread to signify the state of ritual purity, some prayer rituals in the morning before the trance state, taking the kavadis out and ritually purifying them, tying milk pots to the kavadis, taking the ritual bath — all of these have to be done before you can think of trance and fitting the kavadi. The individual must be in a full state of readiness and purity, and the kavadi must be blessed before the final rituals can be begun.

E.K.: How deep do the spears go in, and what is their size?

C.V.B.: I normally take two vels, each of about nine inches in length, one of which goes through the tongue and the other through the cheeks. I also take 108 hooks which are placed in the torso. The vel through the tongue signifies silence (mauna) which indicates that you have relinquished the gift of speech to concentrate on the Divine; the hooks indicate the transience of the fleshly body, and the fact that you have entrusted your own welfare to Murugan.

Some devotees take larger spears which may be up to two metres in length. These are also found in India, and are a recognized form of kavadi worship.

E.K.: What is the composition of the ash which is used in the ritual?

C.V.B.: The sacred ash — vibhuti — is made of burned cow’s dung. In the Hindu tradition all of the cow’s products are sacred. Burning is an act of purification. The burning of the dung forms a fine white ash which is used for a variety of ritual purposes. Vibhuti is regarded as “cooling”, and also has recognized medicinal qualities.

E.K.: Does every kavadi bearer represent a temple or is it also an individual?

C.V.B.: The kavadi is a ritual burden born by the devotee, but it is constructed to represent a shrine in which the deity is carried. This is especially obvious with the larger kavadis (the �mayil’ or peacock kavadis) but is also seen in the smaller �paal’ or milk kavadis. The kavadi bearer may take a kavadi to assist other people (I took a kavadi for my mother-in-law in 1983, for my grandson in 2004, and for my wife in 2005), but in actual fact the kavadi is taken by an individual and signifies a relationship between devotee and deity.

E.K.: How big is the group of people you are in, and the number of kavadi bearers in this group?

C.V.B.: I have taken fifteen kavadis, thirteen of which have been at Batu Caves (1981,1982, 1983, 1985, 1987, 1988, 1989, 1992, 1995, 2000, 2004, 2005, 2007), one in Penang (1997), and one in Palani, South India. In general, the number of kavadi bearers taken at Batu Caves has consisted of about thirty people, comprising a cross section of society, and including a number of tertiary educated people, a mixture of men and women, and a spread of age groups. (The idea that only uneducated people bear kavadis, an idea which seems to have some belief among certain Western academics and journalists, is totally incorrect.) With those who assist the kavadi worshippers, the number of people who leave the temple in our group is probably about 120 people.

I should add that it is difficult, if not impossible, to bear a kavadi on your own. You need people to provide protection from the crowd, to guide your progress, to give you water, and to massage your legs. These are people upon whom you must rely. They too, are fellow devotees.

E.K.: Are there any stops in between for religious acts, and if so, what are these?

C.V.B.: The main stops are for rest between bursts of dancing, for water, and for the massage of legs. One of the supporting group will take a stool upon which the kavadi worshipper will sit from time to time. On the way devotees should acknowledge the temples and shrines which he/she passes.

E.K.: Do you always start at the same point?

C.V.B.: At Batu Caves, I have always started at a temple (the Sri Maha Mariamman Temple) in the Indian Settlement near the Caves. The pujari in this temple always performs all of the necessary rituals properly, cares about the welfare of his devotees, and provides proper spiritual advice.

E.K.: What is the distance you walk to the Caves?

C.V.B.: Probably about four kilometres, but given the size of the crowd this takes a considerable amount of time to cover. In Penang the distance was nine kilometres, and in South India the foot pilgrimage covered 120 kilometres between the place of origin (Palakkad, in Kerala) and the final destination of Palani.

E.K.: What do the 272 steps to the Caves do to you?

C.V.B.: I find that when you reach the steps you feel a powerful pull to ascend. You feel a sense of spiritual anticipation which urges you on, and a surge of energy to go up the steps to fulfil your vow.

Climbing the steps represents part of the cosmic journey of Lord Murugan, but it also symbolizes ascending the charkas, or the main spiritual centres, which lead from ignorance to enlightenment. It is a highly emotional part of the pilgrimage.

E.K.: Is being in the Caves the final highlight?

C.V.B.: It is a major highlight. When you reach the Caves and dance before the deity, you have completed your pledge to Him, and you are in a state where you can now offer your physical burden (the kavadi) and your psychic burden to Him. But you also exchange energies with the deity, and understand that He is with you always. It is a moment of powerful transformation and profound awareness.

E.K.: Can you describe your mental state during the whole procedure?

C.V.B.: Awe. This has deepened over the years, and even now, after my fifteenth kavadi, I feel a sense of overpowering joy. In 1983, when I took a kavadi — my third — for my mother-in-law, who was “hopelessly” ill with cancer (“hopelessly” according to Western doctors), I felt a sense of peace, and love and tranquillity which was overwhelming, which could never be described in words, and which changed my entire spiritual perspective. This lead to my decision to become a full vegetarian, to take a Hindu name (Vadivella), and to intensify my own spiritual disciplines. I have found over the years that this process has been repeated; that the love I feel is Divine, and the awe I feel is beyond words. But I also feel a sense of keen awareness which makes me receptive to far more subtle and deeper layers of consciousness, and this has had a huge impact upon my outlook.

The trance state is quite a strange phenomenon. The first stage of trance is often intense, and this is when the hooks and vels are inserted. But the later stage is a form of greatly heightened consciousness, a sort of super-awareness, and allows the passage of feelings, thoughts, processes and reflections which seem to arise from a much more profound force. This feeling is that of Divine Grace.

E.K.: What is the role of women in Thaipusam? Does your wife bear a kavadi with spears or hooks as well?

C.V.B.: Women do not generally take the larger kavadis, but there is no reason why they shouldn’t. There are a large number of women who take vels, and a smaller number who take spears and the larger kavadis. Many women bear milk pots (kudam), but I have seen women in India who take large spears and mayil kavadis. My wife, Wendy Valli, has taken three paal kavadis, as has my elder daughter.

E.K.: What happens to your state of mind after Thaipusam?

C.V.B.: The Australian novelist, Thomas Kenneally, talks of the “scalding sight of God which disrupts the senses and re-arranges them on the higher level”. I think this is the best description of how I feel after taking a kavadi. When I first took a kavadi in 1981, I was a person who remained deeply influenced by a corrosive form of Western scepticism, and I was unaware of how personally destructive this was upon my psyche and upon my relationships with those around me. Each Thaipusam has provided me with a series of subtle “messages” which are guides to life, and which have resulted in challenges in spiritual terms. These insights have shown me the sort of creative awareness that is possible to attain as a spiritually functioning human being, and the major challenge has been to try to absorb these insights into my daily life back in Australia. I think that in many respects I am a better, more thoughtful person, than I once was, and I now find the world a meaningful place, filled with magic and wonder. I try to apply the lessons — humility, awe, peace, love, tenderness, respect for diversity, honesty to self and others — that Thaipusam has taught me. Each Thaipusam my feelings of gratitude deepen, and make me more determined to grasp the full lessons of this wondrous gift called Life.

E.K.: How do you react and interact with the growing number of tourists?

C.V.B.: At first I was quite upset by the intrusions of tourists, and the way in which they would take photographs. But now I am far more understanding — the photo taking is an occupational hazard! — and I try to ignore anything which might detract from my concentration on the Divine. Many tourists are intensely curious; they have never seen anything like Thaipusam, and are often deeply moved by the displays of devotion that they witness. I am often approached by tourists wanting to know what the Festival is all about, and genuinely interested in what they have seen.

On the other hand I am disturbed by some who do not respect the sanctity of the Festival, who see it as a spectacle rather than an occasion for deep piety, or who make value judgements about the behaviour of other people. I would like to see the Malaysian Hindu authorities prepare some sort of leaflet which could be provided to tourists which explains Batu Caves and the festival of Thaipusam.

Click here to comment on or discuss this interview

This interview is courtesy of and was conducted by Ego Kornus (iam:Ego Kornus) of KavadiBlog. For bibliographical purposes it was first published here on April 3rd, 2007.