From Exhibitions to Entertainers. PART I “The love of beauty in its multiple forms is the noblest gift of the human cerebrum.”The modern Western perception of tattooing has been indelibly marked by its cultural association with the sideshow and its historical predecessor the traveling exhibit. Tattooing as an art form cut its teeth and developed in the West in great part due to the desire for and profit to be had by exhibiting tattooed people. At many circuses and carnivals one could not only see a tattooed marvel but also receive a permanent souvenir from the traveling tattoo artist on the lot. For years, tattoo artists commonly spent most of their time on the road with such shows, possibly also serving as its banner painter, and then wintering at a street shop location. A great example of such an artist, and an inspirational tale in its own right, is Stoney St. Clair whose life and work was documented in what is often considered a seminal work in the history of tattooing: Stoney Knows How (BOOK, VHS).

In AD 325 Constantine, whose name would later be used by a tattooed attraction in a sort of poetic justice, banned tattooing in the Roman Empire. In AD 787 Pope Hadrian I issued a papal edict against tattooing. Of course, this did not stop the crusaders sent by later popes to wage war for the holy land from getting tattooed while there. However, for the most part these and other similar laws issued forth reflected a general Western prejudice that had developed in the culture against tattooing. Many alleged “experts” considered tattooing to be a sure sign of people being uncivilized and particularly savage. And it was with just such “savage” peoples that exhibitions of tattooing began to gain prominence. In 1691, Giolo (or Prince Giolo) was taken by William Dampier in settlement of a debt. Dampier fixed upon the idea of exhibiting the tattooed Prince. The marketing for Giolo created a sensation in England, but the exhibition was ultimately doomed as Giolo came down with small pox and died shortly after arriving from the Philippines. Despite the exhibition not meeting expectations, the successful marketing drew attention and many people realized the potential profit in exhibiting native peoples and particularly those with tattoos. In 1774 a South Seas islander from Tahiti named Omai returned to London aboard a ship from one of Captain Cook’s expeditions. Omai had only minor tattooing, mainly on his hands, but the fact that he was tattooed was a major part of his marketing and often exaggerated. Playing the role of the �noble savage’ Omai was incredibly well received and successfully toured most of England, including a royal audience. In 1776 he returned home. With the success of these exhibits it was only a matter of time before Westerners themselves would hit upon becoming the attractions. Many sailors made efforts to exhibit their �souvenir’ tattoos but the standard for non-native exhibits would be set by a man named Jean Baptiste Cabri. Cabri was discovered in 1804 living among the natives in the Marquesan Islands by George Langsdorff. Cabri, a French deserter, had �gone native’ and been extensively tattooed while living on the islands. Returning to Russia with Langsdorff, Cabri not only exhibited his tattooing but also told exaggerated tales of his life among the natives, effectively moving into performance and creating the archetype that would be followed by tattooed people for centuries to come. With good initial success he was able to successfully tour Russia and much of Europe. However, by 1818 his notoriety had declined and he had died in his native France. After Cabri came Rutherford in 1828. John Rutherford, the first extensively tattooed English exhibit, returned to Bristol after having left for New Zealand in 1816. Rutherford was heavily covered in Maori tattoos and spun fanciful tales of shipwreck, abduction, and living with the natives. Rutherford was able to better capture the imaginations of his audiences than Cabri and further developed the basic elements and progression of the tales that would be mimicked by other tattooed people for more than a hundred years.

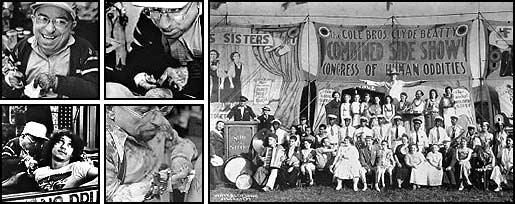

L-R: Giolo, Omai, Cabri, and Rutherford.

In 1873, O’Connel was succeeded by Prince Constantine (like the pope) in Barnum’s show. Constantine was a Greek man also known as Alexandrinos Constentenus aka Djordgi Konstantinus aka George Constantine and Captain Constentenus. He was very likely the most successful exhibit to date and for some time, commanded a salary of $1000 a week while also making good sales on his own book of adventures. This success was most likely due not only to his talent for spinning yarns but even more so for the quality and extensive nature of his tattooing. Constantine was covered with finely detailed Burmese style tattoo work. He is also notable for probably being the first person to completely tattoo their body with the specific goal of becoming an exhibition in mind. In the years to come many would follow his model. And, future exhibits were not the only ones he would inspire � it is said that the legendary tattoo artist Charlie Wagner was so struck upon seeing Constantine that he set out to learn to tattoo. This resulted in his finding an apprenticeship with James O’Reilly, who patented the first electric tattoo machine. With Constantine we enter into what might be called the golden age of the tattooed exhibits. A time when hundreds of people got tattooed and made their living as part of traveling shows and museums. Also, the time in which we see the tattooed women come to the stage and even eclipse the men. This era, the decline of the traveling shows, and the return of the tattooed exhibit as performer in the modern sideshow renaissance will form the second installment of this two part column.

Selected Sources and Suggested reading: Much of the original research and work for this column was also used for the BME Encyclopedia which contains a number of entries related to and expanding upon the information presented here.

View all columns by Erik Sprague | Return to BME/News |