|

Raven and Daemon Rowanchilde are the owners and founders of Toronto's Urban Primitive Design Studio, a way of thinking and a bodyart studio embodying a tribal consciousness for modern information times. Together they provide clients with a more meaningful bodyart experience than many studios are able to provide. Their comprehensive online home gives their full contact information, and is the source of the photographs used in this interview. |

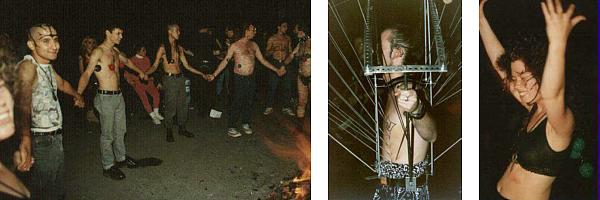

Also at that time, Fakir Musafar had been actively involved in his own explorations of pain rituals. Initially Fakir's focus was to simply explore techniques used by other cultures to attain ecstatic states of consciousness. These early explorations appealed to Daemon and I.

From a physical standpoint, the G.C. significantly reduces the risk of infection with proper knowledge of pre and post suture preparations. The G.C. must also be prepared to deal with the possibility fainting or falling dancers. Psychological concerns present more potential problems. People have spontaneously relived memories of childhood abuse during a ball dance. A few of the people that I interviewed for my online book talked about such experiences. The G.C. has to be aware that when someone experiences a painful memory, they may: a) need to stop the ritual immediately b) decide (with gentle encouragement) to continue with the ritual to work through the trauma, and c) require an empathetic listener during the download after the ritual.

BME:

How do these rituals relate to BDSM? Are people who find meaning in a ball

dance usually into "alternative lifestyles", or can it be meaningful for

people without prior experience?

RAVEN:

Both. People with no prior SM experience had the advantage of no

pre-conceptions or expectations that can sometime colour the experience.

On the other hand, SM folk have the advantage of familiarity to work

through the pain and push their limits. Many people assume that SM folk

are more inclined to these rituals, but this is not generally the case. A

lot of SM folk want SM to be accepted by the mainstream. The erotic

platform of "kinky sex" was easier to consume and digest by the mainstream.

Spiritual ritual involving pain, however, are considered so far "out there"

that they resist being appropriated as fashion. I say, "resist" because,

as we later found out, the power of the commodification machine is

extremely powerful and this threatened to turn rituals that were very

meaningful to many people into a fad.

The most blatant example is an article in the (second) premiere issue of In the Flesh that featured a young man named Devin Murfin hanging from flesh hooks. He claimed he was doing an O-kee-pa ceremony and that he was planning a "gang hang" which he planned to videotape and then sell the tapes.

Murfin hasn't a clue what an O-kee-pa ceremony is. There is a four hundred year old history surrounding the O-kee-pa (sometimes referred to as the Sundance) that is culture-specific to the Plains Indians. The ceremony is very elaborate and involves an entire year of preparation and the participation of the entire group. I was very fortunate to have participated in a peyote ceremony with Cheyenne and Arapaho people in Oklahoma. Later, my Cheyenne friends invited me to attend a Sundance ceremony. The Cheyenne perform the Sundance every summer. The ceremony allows them to renew and revitalize their culture. This is particularly important when we consider the attempts at cultural genocide they have endured.

Unfortunately, Murfin hurts this renewal process with his blatant appropriation and commodification of the ceremony. Sparrow and I wrote a very long letter to the editors of In the Flesh discussing our concerns. They published our letter and promptly dismissed us using the same lame arguments that have justified cultural genocide for hundreds of years.

BME:

Your one-year-book, "Transformation in the Urban Jungle" discussed some of

these issues -- What is this title referring to?

BME:

Your one-year-book, "Transformation in the Urban Jungle" discussed some of

these issues -- What is this title referring to?

RAVEN:

I wrote the book in response to the growing media misrepresentation of

people exploring spiritual rituals involving pain. I also wanted to

address the issue of cultural appropriation in a way that reflected the

attitudes and concerns of the people that I interviewed. Transformation

in the Urban Jungle refers to the healing component of spiritual rituals

involving pain. I wrote the book in an academic style to demonstrate to

readers that a large body of theoretical literature supports some of the

ideas in the book. I also wanted to challenge some of the long-standing

theoretical notions in the psychiatric community regarding

"self-mutilation". We turned the book launch into a ritual. On the Winter

Solstice, I gathered a group of twenty close friends and acquaintances to

participate in a piercing ceremony. I thanked everyone for attending and

asked that the focus of the ceremony be that the book enlighten both

participants and non participants of such rituals and promote

understanding. My friend Peter Dawson lead a short meditation and had

everyone bless a blue stone for me to hold when Maribelle did my Aphrodite

piercing (aka Christina). Sparrow launched the book onto BME just as

Maribelle pushed the needle through freehand. I screamed in a way that I

hadn't done even when Jim Ward pierced my clitoris. The room went silent.

It was a moment that I could only describe as epiphany. I burst into tears.

Since BME published the book over a year ago, I've had scores of people

emailing their thanks. The book also generated considerable academic

interest; in addition to graduate students exploring body modification for

their theses, local psychologists have initiated new research that

re-examines the idea that self-injurious behaviour may actually have a

therapeutic effect.

BME:

Some people have objected that events such as Kavadi, ball dances, and

other rituals that borrow from the religious and spirital ceremonies of

other cultures, and that this "theft" is offensive to the original culture.

As someone who has organized these events, how would you respond to this?

RAVEN:

Those are valid objections. Daemon and I were very conscious of

informing participants that we were simply exploring tools or techniques

for transformation, much the same way that tattooing, piercing,

scarification or branding can be tools for transformation. We never

attached any culture-specific meaning/s. We didn't dictate what the

participants should think or feel; the ceremonies were very individual

experiences. We did provide a pre-ritual workshop outlining methods,

addressing questions and concerns and providing practical breathing,

chanting, movement exercises to facilitate a more powerful and integrated

experiences. Overall, participants had very positive experiences.

DAEMON: We're exploring the past not because we want to return to the past; that's impossible. Our intention is to draw inspiration from the past and use the insights that we gain to inform the present and future. One example that comes to mind, is my recent experimental archaeology project with Dr. Julian Siggers. Julian works for the Discovery Channel. When I tattooed Julian several years ago, we talked about our mutual interest in indigenous body art and formed a strong friendship over time. Julian wanted to do a television piece on the Ice Man. Julian hypothesized that a sharp, pointed instrument found in a leather pouch attached to the Ice Man's clothing, may have been used for tattooing the designs on the Ice Man's body. As part of the presentation for Discovery Canada, Julian duplicated the Ice Man's tool using different materials: caribou antler, cow bone and chert. Julian didn't tell me which tool was the exact replica of the one found on the Ice Man. On camera, I hand tattooed Julian with each of the tools. The one that worked the best was the cow bone and I used that to complete his tattoo. After I confirmed that the cow bone worked the best, Julian informed me that the instrument found on the Ice Man was made of cow bone.

BME:

What does someone need to be careful of to be respectful to other cultures

when borrowing elements of their rituals?

RAVEN:

Honour the source of your inspiration in some way during the

ritual. Be clear that you are not claiming access to culture-specific

rituals or their meanings.

DAEMON: And if possible, ask.

BME:

Tell me a bit about your involvement with North American native groups

seeking to revive traditional ritual and body art.

RAVEN:

During the course of researching and writing my book, I met two

Native women who had very interesting tattoo designs on their arms and

face. Initially, they wanted to contact Daemon and I because they were

interested in the work we were doing with transformation rituals. After I

interviewed them for the book, we discussed our mutual interest in

traditional body art forms. They asked me if I had any sources that

weren't Europeanized woodcuts a la Theodore De Bry, etc. Unfortunately,

most of the pictoral sources of traditional Native body art is a

fabrication of the European imagination. Many of the representations were

based on the descriptions of European travellers which were then

re-interpreted by European artists who had never seen the people. What

little documented information we have of Native Canadian tattoos was

written by the Jesuits. I spent an entire day at the U of T library

pouring over volumes of the Jesuit Relations looking for decent

descriptions of tattoos. A motor vehicle accident curtailed my research

activities, but I understand that similar research (perhaps more

appropriately) is being undertaken by others in the Native community.

BME:

What role does your own pagan background and belief structure play in all

of this?

RAVEN:

My pagan spirituality informs everything that I experience.

BME:

In the first issue of "Body Play" there is a photo of you getting branding

by Fakir -- Was this your first experience with branding?

BME:

In the first issue of "Body Play" there is a photo of you getting branding

by Fakir -- Was this your first experience with branding?

BME:

How did you learn? If someone wants to learn, how should they go about that?

RAVEN:

Source as much information as you possibly can. Then... practice,

practice, practice.

BME:

Does ritual play an important role in branding?

RAVEN:

Branding, perhaps more so than tattooing or piercing, lends itself more to

ritual experience. I believe that branding, by virtue of olfactory

stimulation and intensity of sensation, can invoke ancestral memories.

Branding also has a profound history of therapeutic and spiritual

application.

BME:

To mark your marriage (tell me if you'd prefer another term), you share

tattoos -- Tell me a bit about the role that body art plays in your

relationship.

RAVEN:

Daemon and I got handfasted in 1989. We wanted to permanently mark

our spiritual committment to one another with ankle tattoos.

DAEMON: Everything that we do, are and will be gets expressed somehow, somewhere in the body.

BME:

How has your personal involvement with ritual and spiritually

transformative body art affected your own life?

RAVEN:

Body art has affected both of us in a very profound way. I

detailed some of my personal experiences in UPTUJ, including getting my

clitoris pierced in a sexual reclamation ritual.

DAEMON: My personal involvement with ritual and spiritually transformative body art has marked points of transition, e.g. my palang piercing literally punched me into a new level of being. It gave me more courage and confidence to make changes in my life. My other piercings, tattoos and brandings also helped me transform psychological programs that held back my spiritual growth.

BME:

Is that why you try to share these experiences with others and help them to

achieve them?

BOTH:

Exactly.

During the years that followed, I put many hours into tattooing and painting. While working on my clients I became much more aware of the process of transformation and the experiences that this process often evoked. These experiences ranged from a simple euphoric afterglow that lasted for a couple of weeks, to a full blown cathartic release that shook the very foundation of their being. I started paying closer attention to the factors that led to these experiences. In the years that followed, I devoted all the time I had to both perfecting my skill as an artist and researching/ exploring the most effective ways to set the ground for a true and spontaneous transformation. I believe these two elements must be both present and in balance to allow a full "tattoo experience" to take place.

In terms of style, I took precision and definition further than it had been previously explored in black tribal design. I sometimes spent twice as long on a piece as someone else, but the quality, flow and crispness of the lines compensated for any extra discomfort and expense. I am presently exploring the marriage of black daemonic tribal with gray watershaded patterning that reflects the energy and vitality of the particular piece and the individual wearing it. This not only further integrates the art with the person, it becomes a personal energetic signature or fingerprint of that person.

BME:

What's the most important thing a person should consider when

getting/planning a tattoo?

DAEMON:

A person should realize that the tattoo is not just being placed

on your body; it is becoming a part of you, an extension of yourself.

BME:

What do you do to help provide that?

DAEMON:

I divide it into three parts:

1) Pre-Tattoo Experience - a full and formal consultation prior to being tattooed, to allow the artist and the client the time to get to know each other and to arrive at the best possible design and placement.

2) "Set And Setting" - creating an atmosphere that will provide the most effective environment and allow for an unrehearsed,spontaneous and open experience. This is further enhanced by allowing the client their input into the choice of music, incense,candles and the people that they wish present for their experience.

3) Post-Tattoo Experience - Including after care, healing and reflection.

BME:

You've said that pain is an important part of getting tattooed. What role

does the ritual of tattooing play, and what role does the end aesthetic

result play? Dependingon the situation, would you "make" the tattoo hurt

more for some people? (You may want to reword that question)

DAEMON:

The aesthetic is as important as the experience. It is a permanent marker

of the experience and when it is executed beautifully, it remains a

positive reminder for the rest of the person's life. As far as the pain

element, tattooing, especially with larger work, is an rite of endurance.

I find that the most powerful experiences occur with tattoos that require

six hours or more to complete.

BME:

What do you think of many people who are starting to treat scarification as

a purely visual event, with no respect for the underlying spiritual event?

What do you think they're missing?

RAVEN:

It is inevitable, especially since the techniques have improved the

overall visual quality, that scarification has become represented more as

an art or fashion form. I hesitate to get dogmatic about the spiritual

component of scarification. While I believe that acknowledgement of the

spiritual allows for a richer experience, it is not for everyone, nor

should anyone insist that it be strictly a spiritual practice.

DAEMON: They're just two different schools of thought which at times do overlap to form a whole new level of experience.