|

||

Body Play: State of Grace or Sickness? Part I: A New Culture is Born

|

||

In body modification, the spirit and body dance together in a rhythmic balance.

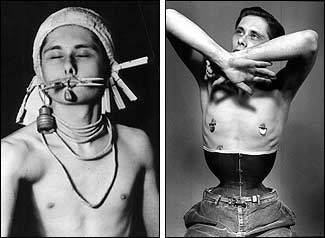

Early Experiments by Fakir Left: Pierced septum (1948), Right: Nineteen inch waist (1959)

For years I haunted libraries, searched archives, and listened intently to the tales of Native American elders were I grew up in South Dakota. I was looking for any trace of sanction for what I felt and practiced in secret. In other cultures I did find acceptance, reasons, and traditions honoring this urge to modify the body. In fact, the mental and emotional states associated with the act (ecstasy, trance, disconnection and disassociation) were frequently considered "States of Grace", not perversion or sickness. I ended my isolation when a wise and understanding mentor encouraged me to "go public" with what I had been doing in secret for so many years. He arranged a showing at the only place where I might find a receptive audience: the first International Tattoo Convention held in Reno, Nevada in 1977. There I "came out of the closet" and showed it all: body piercings, contortions, large blackwork tattoos (novel in 1977), disconnection from body sensation while on beds of blades and spikes. The highly tattooed and pierced audience ate it up. They understood and honored in me what had also moved them to mark and pierce their own bodies. From that moment on, I felt we started making our own new culture and social sanctions.

Left: Reno 1977; Fakir pulls a tattooed belly dancer across the Holiday Inn ballroom with his new deep chest piercings attached to a valet cart. Right: Reno 1977; Fakir lays on a bed of nails and Sailor Sid then breaks stone blocks on his back with a sledgehammer.

Whether we were Native Americans returning to traditional ways, or urban aboriginals responding to some inner universal archetype, one thing was clear — we had all rejected the Western cultural biases about ownership and use of the body. To us, our bodies belonged to us! We had rejected the strong Judeo-Christian programming and emotional conditioning we had all been subjected to. Our bodies did not belong to some distant God sitting on a throne; or to that God's priest or spokesperson; or to a father, mother or spouse; or to the state or its monarch, ruler or dictator; or to social institutions of the military, educational, correctional or medical establishment. And the kind of language used to describe our behavior ("self-mutilation") was in itself a negative and prejudicial form of control and domination. At first, these newer views about the body and what it could be used for were only expressed or practiced in the budding subcultures of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s — in hippie, punk, radical sex, gay, sadomasochistic, tattooing and pierced body circles. My own connection with these subcultures began as far back as 1955 when I started to share body piercing and other body rites with other individuals and various cultural sub-groups. I needed a meaningful name to call our now socialized (versus isolated) practices. To me it had always been "play", so I coined the term "Body Play". To me, Body Play is the deliberate and ritualized modification of the body whether permanent or temporary. I felt it as a deep-rooted, universal urge that transcends time and cultural boundaries. As a behavior, Body Play is either accepted, condoned and made a part of the culture — or it is seen as a threat to established social order and institutions and forbidden or made unlawful.

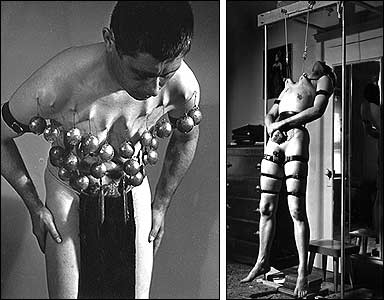

More of Fakir's Early Experiments Left: Wearing lead (1962), Right: O-Kee-Pa (1963)

In the 1970s, an eccentric millionaire in Los Angeles brought a number of "body players" together. His name was Doug Malloy and I first met him in 1972 after he had seen some photos of my early experiments dating back to 1944. We used to meet monthly in the back of Los Angeles restaurants for what we called "T&P (tattoo & piercing) Parties". The numbers were small, never more than ten to fourteen persons, all we could gather in those days. We shared experiences, did "show-and-tell" and often arranged to meet again later in the day to help each other implement various piercings and bodymods. Over a course of several years, we developed and defined what would eventually become the lexicon of contemporary body piercings: types of piercings, techniques to make them and tools. At one meeting in 1975 I recall we tried to list everyone we knew in Western society who had pierced nipples. There were only seven, all males, except one woman who had been pierced in 1965. None of us in that group could conceive that we would, within a few years, have pierced hundreds of nipples, and that many of those we pierced would later also pierce hundreds more. By the late l980s the sight of pierced nipples — thousands of them — would be commonplace at all large subculture gatherings like Folsom Street Fair in San Francisco. By the late 1980s, other forms of body modification and socialized body rituals were also emerging from the shadows of American subculture: tribal tattoos, cutting, branding, trance dancing, suspensions and body sculpting. In many ways, I felt responsible for encouraging some of it. In a quiet way in l983 I proposed production of a book on body modification and extreme body rites to ReSearch Publications of San Francisco. They began by taking twenty-seven hours of interviews with me. Along with this edited text, I provided about seventy photos of myself; self-portraits I had taken during my thirty years of secret experimentation. To round out the book, the publishers added other individuals who were also pioneers in modern body liberation. I suggested the title: "Modern Primitives" (a term I had coined in 1978 for an article in PFIQ magazine to describe myself and a handful of other "atavists" I knew). The net result was a book of unprecedented popularity and influence in the subcultures. Since its release in 1989, this book has gone through many reprints and sold tens of thousands of copies. After fourteen years in print, it is still being sold. As a result of this one book, thousands of people, mostly young, were prompted to question established notions of what they could do with their body — what was ritual not sickness, what was physical enhancement not mutilation. The Modern Primitives Movement was born!

Yours for safe inner journeying, NEXT IN PART II: The New Culture Matures

Fakir Musafar is the undisputed father of the Modern Primitives movement and through his work over the past 50 years with PFIQ, Gauntlet, Body Play, and more, he has been one of the key figures in bringing body modification out of the closet in an enlightened and aware fashion. For much more information on Fakir and the subjects discussed in this column, be sure to check out his website at www.bodyplay.com. While you're there you should consider whipping out your PayPal account and getting yourself a signed copy of his amazing book, SPIRIT AND FLESH (now).

Copyright © 2003 BMEZINE.COM. Requests to republish must be confirmed in writing. For bibliographical purposes this article was first published July 4th, 2003 by BMEZINE.COM in Tweed, Ontario, Canada. View all columns by Fakir Musafar | Return to BME/News | ||