AN INTERVIEW WITH

PHILIP BARBOSA

“I don’t paint nature, I am nature.”

- Jackson Pollock

The first time I met Phil Barbosa, I almost didn’t.

It was the winter of 2002, I had a backpack full of beer, and I was wandering the streets of Toronto’s east end, trying to find a party. Phil had issued an open invitation to his house on this particular Friday night, and I figured it was time I got out and met some people from the BME community. Granted, I was hardly a social butterfly — the chances of me actually striking up a conversation with a complete stranger were only slightly worse than the chances of me arriving by spaceship — but hey, I thought, it’s a party! Worst-case scenario, I take up my usual position on the wall, polish off a six-pack, and call it a night.

As luck would have it, I got absolutely lost. Not only was I not going to know anybody, but now in the event that I actually made it to the party, I would be instantly demoted from “fashionably late new guy” to “schmuck who couldn’t even find the place, then sat silently in the corner creeping everybody out all night”. After circling the neighborhood more times than I’d care to admit, I finally stumbled upon what I hoped to be the right home, rang the doorbell, and was greeted by a man who resembled Phil Barbosa — I wasn’t quite sure yet, as I was still somewhat blinded by shame and nervousness. Phil, however, was a gentleman; he wouldn’t have known me from Adam had I not introduced myself, but he greeted me like an old friend nonetheless and invited me in.

The party, as it turned out, consisted of four people at the time — including me. I was still partially frozen and couldn’t tell if this was better or worse, though everybody seemed nice enough. Phil, especially, made an effort to make me feel welcome, making what seemed to be a deliberate effort to “buddy up” with me throughout the evening to make sure I didn’t get left out due to my overwhelming lack of social skills.

For many people, Phil makes a similar first impression; he’s remarkably friendly, doesn’t have a prejudiced bone in his body, and has an uncanny ability to make people feel comfortable in their surroundings. As a professional photographer and a facilitator of suspensions, Phil puts these traits to use every single day. I recently caught up with Phil about his career behind the camera, his work with BME, and Ascension, his new art exhibit that marries two of his greatest loves — photography and suspension. * * *

BME: |

When did you first develop an interest in photography? What started it all?

|

PB: |

I started back in high school, taking a high school photo course just as a way to fill up the time and get an art credit. I wasn’t very good at it at first, but I really liked it, and I ended up photographing a lot of my friends who were in bands when they were rehearsing or playing shows — just normal things you do when you’re hanging out with your friends when you’re not in school — but things just spawned from there.

Eventually though, I got a job at a [photography] studio for catalogues. It was just a summer job, but I actually really enjoyed the work; I started off as a shipper/receiver, but then one day they asked me if I could paint [walls], and I said, “Sure! I can work a paint roller.” So there was that, and from there I started working as a photo assistant, and afterwards I went on to college. I guess all I’ve ever really known is photography.

|

BME: |

And from college you moved into shooting the wedding and portrait circuit — how successful have you been in that field?

|

PB: |

I’ve been moderately successful, but it’s up and down. With weddings and portraits, you’re only as busy as what the industry dictates as far as how much people want to spend that year. Recently, it’s become that in the wedding and portrait industry — at least in Toronto — people aren’t spending what they used to on higher quality work. Often with wedding photography, people just assume that a picture is a picture is a picture, and if they can pay $500 to have somebody there with a camera, then that’s fine — but that’s really hurting people like me who are trying to produce really high-quality work from start to finish. I’ve had to turn away a lot of clients who come in and say, “Well, I only have this much money, and I want you to shoot my wedding, and I want you there for 12 hours”, and I say, “Okay, well that’s fine, but I want $2,500” or whatever it’ll cost me to be able to do it properly — and then they turn around and say, “Oh, well my uncle’s got a digital camera, I think he can do it for $500.” You know, if you want a nice car, you pay for it — unfortunately that’s not always the way people think in this business. I mean, if someone walks into a Mercedes dealership and says, “I don’t really want to spend that much money on that brand new car there, but so-and-so over at the Toyota dealership offered me one for $20,000”, how can you compete with that? I’ve been moderately successful, but it’s up and down. With weddings and portraits, you’re only as busy as what the industry dictates as far as how much people want to spend that year. Recently, it’s become that in the wedding and portrait industry — at least in Toronto — people aren’t spending what they used to on higher quality work. Often with wedding photography, people just assume that a picture is a picture is a picture, and if they can pay $500 to have somebody there with a camera, then that’s fine — but that’s really hurting people like me who are trying to produce really high-quality work from start to finish. I’ve had to turn away a lot of clients who come in and say, “Well, I only have this much money, and I want you to shoot my wedding, and I want you there for 12 hours”, and I say, “Okay, well that’s fine, but I want $2,500” or whatever it’ll cost me to be able to do it properly — and then they turn around and say, “Oh, well my uncle’s got a digital camera, I think he can do it for $500.” You know, if you want a nice car, you pay for it — unfortunately that’s not always the way people think in this business. I mean, if someone walks into a Mercedes dealership and says, “I don’t really want to spend that much money on that brand new car there, but so-and-so over at the Toyota dealership offered me one for $20,000”, how can you compete with that?

It’s how the industry’s going right now, and a lot of it, unfortunately, has to do with the media and what people perceive as what acceptable quality is. And when you compare it to when photographers in, say, the 50s had a really hard time capturing images and getting what they wanted, people just don’t care as much now — the mindset is, “get it out as fast as you can, it doesn’t matter if it’s in focus or whatever as long as you’ve got a reasonable idea of what the image was.” That said, there are a few people who are willing to pay a bit more money and will keep me fed, which is nice to see. Some people do understand that if you’re paying for a service, you get what you pay for.

|

BME: |

When did you discover BME?

|

PB: |

“I was not only able to gain the trust of some pretty secretive individuals, but I was able to get them to twist their nut sack in a knot for me... repeatedly.”

|

I first found the site when it was still bme.freeq.com, back when I was 18 or so and first started college and discovered the Internet. Actually, I guess I discovered the Internet in high school, but when I was in high school we only had one computer in the library that had it, and the librarian would sit and look over your shoulder [while you used it]. So, even though I had a PA piercing at the time, I couldn’t really look it up online, you know, log onto a search engine and type in “genital piercings”. But, when I was in college they had these giant computer labs, and we were told that we should get an email address through the college and go and use these things — they’re open till midnight so go have fun — get on chat rooms and explore whatever you need to. So when I walked into the computer lab, I sat down and immediately typed in “body piercing”, found BME — which, at the time, was really small — and read it cover to cover, so to speak. And after that I checked it every day, so whenever there was a new cover it was a big exciting thing for me. Then I remember when BME Hard was created and became a paid portion of the site and how upset I was — the first year of college I didn’t have a credit card so I didn’t have a way to pay. I mean, I had photographs of my own genital piercings that I’d taken [that I could have submitted], but the labs were still monitored to a point, so I couldn’t feasibly put pictures of my own genitals on a flatbed scanner and send them.

|

BME: |

How did you begin a working career with BME?

|

PB: |

Phil and Shannon Larratt after ModCon ’99 |

I was just on BME one day, and I saw this announcement about this private convention called ModCon — there were just little bits of information, and to be considered for a private invite you had to email Shannon Larratt. So, I emailed Shannon saying, “Well, here’s my deal, I’ve got X amount of genital piercings, I’ve done my own meatotomy, and I’d like to go to your little party and meet other people who look like this”, and I got an email back from him saying I was on the short-list for attendance. He’d mentioned there’d be photographs taken as well, so shortly after, I emailed him and said, “Hey, I’m a photography student, if you need help, I could provide lights, I could provide assistance to you”, that sort of thing, and he replied asking if I’d like to photograph the event! I sent him some crappy portraits I’d done in college just to show that I actually understood how lighting works and how the camera works, and then I got a message back saying, “I’d like you to photograph this for me. I’ll pay you a little bit of money.”

So I shot ModCon for four years, and it turned into me not just being the photographer, but I became a co-coordinator for it — just a general runner person — and one of the core staff every year.

|

BME: |

And then you ended up being the photographer for what became the ModCon book. Did that have a real effect on your career?

|

PB: |

It was pretty cool, but it hasn’t particularly affected my real career; the average wedding planner hasn’t heard of ModCon, and hasn’t heard that I’d photographed the ModCon book — I don’t really know how well it would go over. It’s two sides of a career that I don’t really associate all the time. It has, however, launched a lot of interest in me — online, mostly. I have met people randomly that recognize my name from purchasing the book, which is kind of neat. It’s never really paid off as this amazing thing to launch my career or anything like that, but I think that’s mostly because I never really used it to; I was more worried about trying to make a career for myself out of stuff that everybody else could be shown.

And there are guys who can photograph a penis, but there are only a few people who can convince anyone to do anything — and I think that’s really evident in a lot of the ModCon stuff. I was not only able to gain the trust of some pretty secretive individuals, but I was able to get them to twist their nut sack in a knot for me... repeatedly. But the first generation of the ModCon book didn’t really get me too much attention, though the second one got me a little more attention in the art-type world that I’m sort of gearing myself towards nowadays. I’m trying get away from wedding and portraits so much, and now I’m using this as sort of a catalyst to get myself some more attention.

|

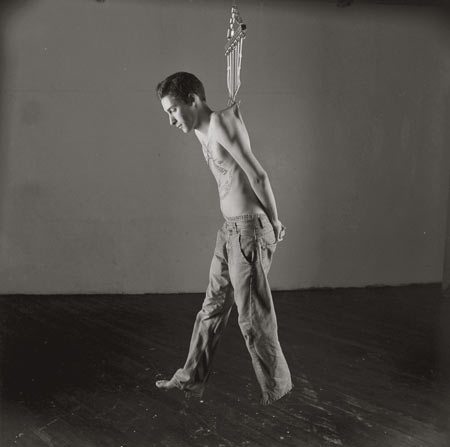

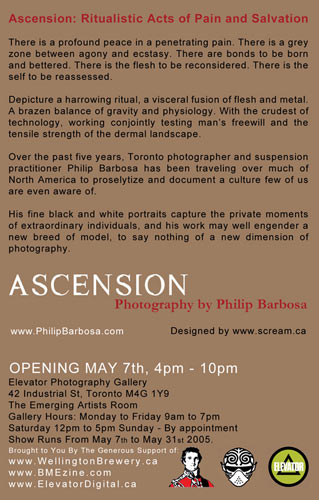

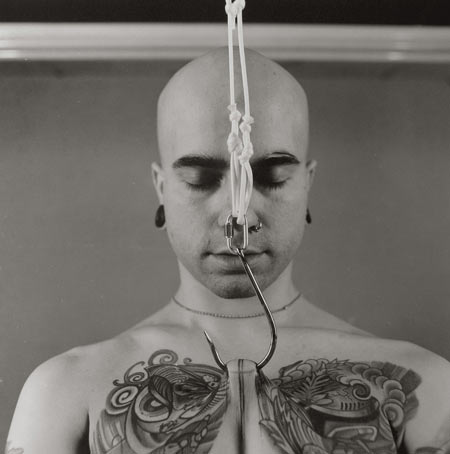

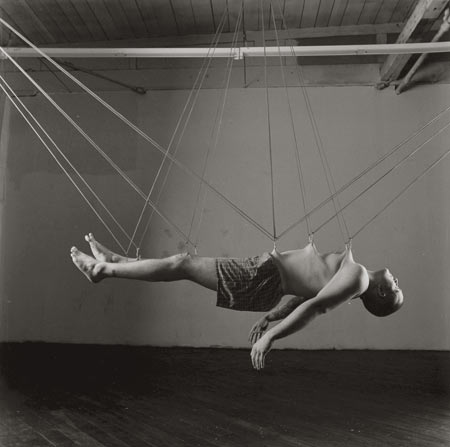

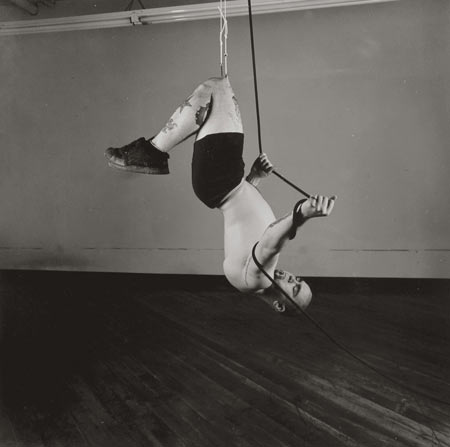

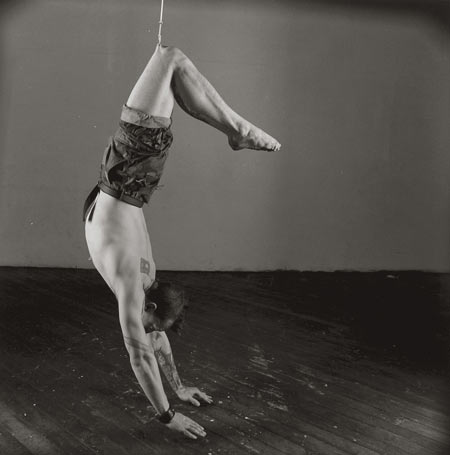

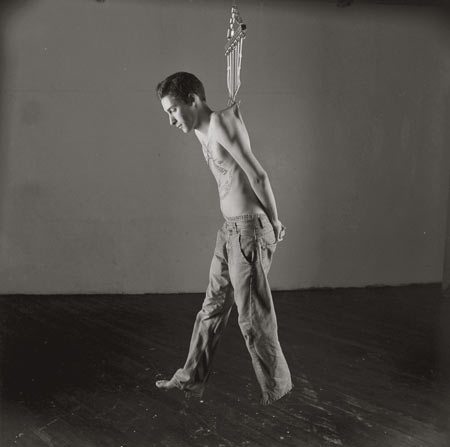

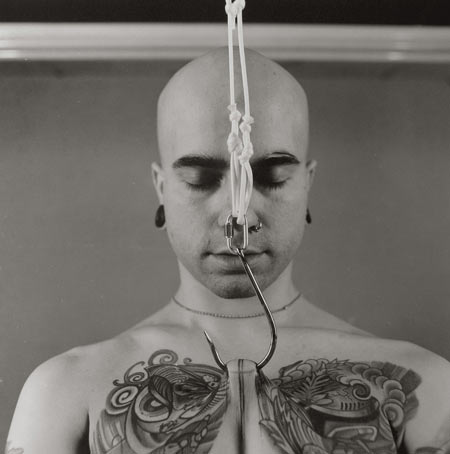

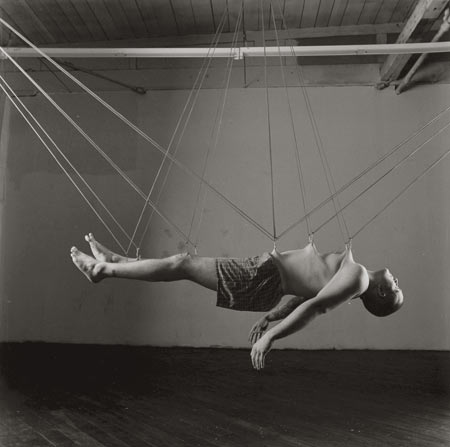

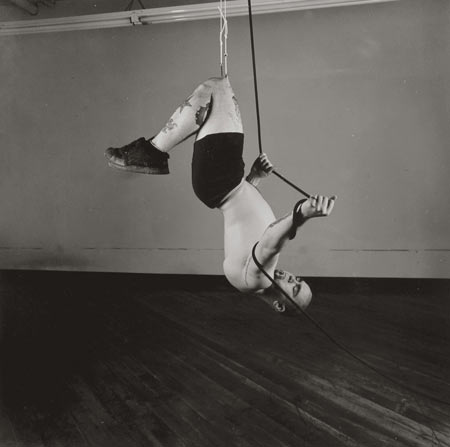

From Phil Barbosa’s Ascension

BME: |

Now, looking at the ModCon book, when one is doing this type of photography, it’s very easy to glorify the work itself in a really over-the-top kind of way, but you don’t seem to go that route so much — it’s more about the people who have the work than the work itself, it seems.

|

PB: |

“You’re sculpting their body into something with light and shadow and exposure, and you’re turning them into something more than what they were when they were just standing there right in front of you.”

|

Yeah, that was a big thing with Shannon and me in the beginning. During our first few meetings before ModCon, I remember going to Future’s Bakery down on Queen St. West [in Toronto], and he told me that he wanted these close-up photographs of genitals... and that was it. There was quite a bit of a difference between how he wanted to photograph things and how I wanted to photograph things.

He wanted a book full of genital piercings, and I wanted to produce a book, produce an interactive CD, produce an art show, so I was looking at the big picture — and I didn’t think that everyone wanted to look at a book full of pierced genitals. We’d all seen Modern Primitives, we’d all seen the stories of the guy with the butterfly penis or the guy whose penis was cut in half, and it had all been done before — what happened to the rest of the guy? When you read that article, there wasn’t the rest of a person there — there was a bit of text about the guy, and a penis... and another penis... and a guy with chains in his penis. Personally, I wanted somebody to be able to look into this and look at the photographs and have them tell this whole huge story — and I thought it was going to tell more of a story if you had a person attached to the penis, so to speak. Otherwise, to me, it’s like you’re just photographing a piece of meat as opposed to a whole person. And when I spoke to these people I met at ModCon — at least the older guys, who I have so much respect for — there was a whole story to everything they’d ever done, and their desires, and everything else, and you could really start to see that. When you look at a technical, medical photograph, there’s no story behind it; you look at those pictures and you think, “Oh, that’s neat, I wonder how they do it?” But, then you look at a photograph of the person and you think, hey, he looks like he could be a mailman or whatever, and you start to wonder what’s going on in that guy’s head that made him do that — what desires did he have that made him want to do something so extreme to his body? And you realize that there’s something so amazing about his free will and the way that his brain works — that he allowed his desires to go that far and decided, “I can’t live unless this desire is fulfilled.”

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

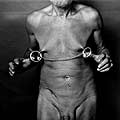

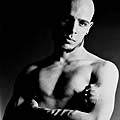

| Portraits by Phil Barbosa from ModCon |

|

BME: |

What do you try to get out of your subjects when you’re photographing them?

|

PB: |

Mostly I just want to make them look and feel like people. At this point, most of the guys that I photograph with the more outward modifications are out there to shock the world and show the world what they’ve got — and most of them normally don’t feel quite so human. If they’ve ever been photographed by anyone else, you know they’ve been treated really different, so I try to approach it with a little bit of humor, and a little bit of general compassion about what they’re doing with their bodies. I’ll usually ask a lot of questions and try to get to know people, and really try to make them feel pretty — you have to make someone feel good about themselves when you’re photographing them. Once you have that trust, you have control, and that’s the whole thing — then you can tell them to do things and get them to start manipulating their body, and you start to create something that’s not just a picture of the person — it’s almost like you’ve created a sculpture. You’re sculpting their body into something with light and shadow and exposure, and you’re turning them into something more than what they were when they were just standing there right in front of you.

|

BME: |

Let’s talk about your show, Ascension. How did this come about?

|

PB: |

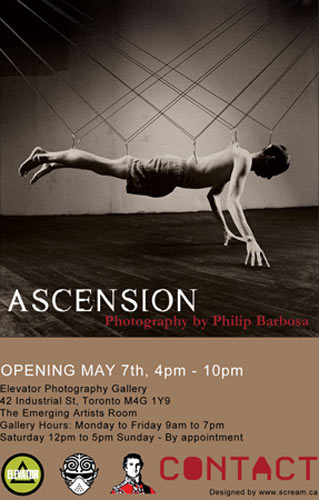

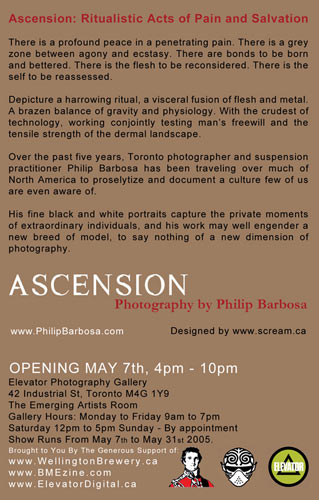

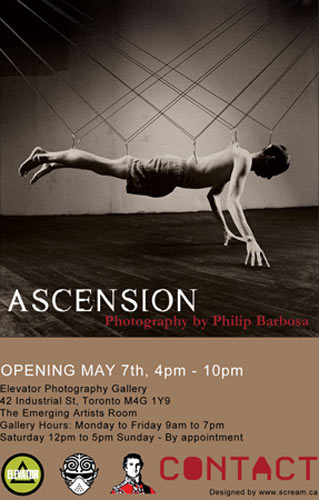

Ascension is part of the Toronto Contact Photography festival, which, for the month of May, is this big promotion of photographic art all over Toronto, and just about every gallery in the city promotes the idea of showing photography. There are openings almost every night of the week, it brings in a lot of international artists, and this year I was lucky enough to actually get my stuff into the festival and have a show in a proper gallery. I’ve done some smaller group shows, but this is my first one on my own. Fortunately for me, the way this one works is that I’m in the Emerging Artists room — a smaller gallery — and there’s a big gallery with a much larger opening for a gentleman named Hasnain Dattu, a big name in international fashion photography — he’s been advertising to Toronto’s elite advertising and marketing clients, collectors, and media people — and every single person has to walk through my show to walk into his.

This is a project I’ve been working on for years and years; it’s fine-art black and white portraits of people that I’ve worked with doing suspensions for at least the last five years. It’s another thing where I wanted to approach it and make it look pretty — I’ve worked with suspension and I know the whole feel of it. To me, if you’re going to do a suspension, it shouldn’t be something that’s just on your list between your transdermals and your branding — it should be something fantastic. And the visuals I tried to create, I tried to make them something truly as fantastic as what everybody felt that they were going through when they were doing the suspension.

|

|  |

BME: |

Being so proficient in suspension yourself — you’re a founding member of iWasCured and a regular SusCon staff member, among other things — what do you get out of watching them, and what do you enjoy about shooting them?

|

PB: |

Admittedly, I have a bit of a problem when I’m photographing someone I’ve known for so many years and telling them to do things; still, it’s a lot of fun shooting and lighting them. I’m really big on lighting — if you’re a photographer or you call yourself a photographer and you don’t know anything about lighting, then as a photographer, you’re not really worth anything. And I’m sure I’ll get a lot of really bad mail for saying that, but I think it’s not just about saying, “I’ve captured a good moment.” I come from a background of being a studio photographer, so I don’t just capture moments — I make them. I create; I don’t just say, “Oh, that was a moment captured in time, that was the decisive moment” — it was just a moment in time where you took a photograph and saw everything. There was a guy in the 20s, a press photographer, who was notorious for getting to the scenes of crimes before the cops were there and making the crime-scene look more interesting — that’s what I try to do. I get off on it that way.

Suspension itself, I enjoy facilitating the experience, just being there — because it’s a life-changing experience for most people. And if there’s that moment where it’s somebody’s first suspension and they really get something from it — that moment where their head is completely turned all the way around — it’s such a huge thing. They’ve gone into shock, they’ve overcome pain, they’ve overcome all these different things, they’ve overcome this extreme fear, because the first time leaving the ground is pretty scary — but once you do it your head spins completely around. The only thing I can think of comparing it to is skydiving, and from talking to guys who skydive and how when they’ve done it, their heads spun completely around. If I skydived, I’d probably be the guy who shot videos when everybody was jumping just so I could be three feet from everyone when they had that moment — you know, that person who was a librarian or a businessperson who’d never done anything crazy in his or her life is like, “I’m going to skydive.” And believe me, I know people who saw suspension like that too; people who’d never really been tattooed and had very few connections with the community, but they heard about suspension and thought, “Okay, this is something I have to do” — and I like being there when that person’s head spins around, because I get to witness one of the most fantastic things ever.

|

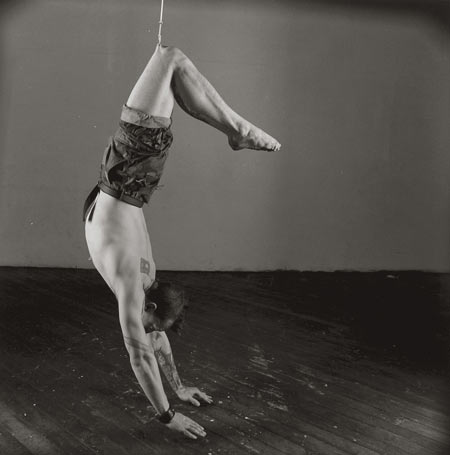

From Phil Barbosa’s Ascension

BME: |

Now, the people who are actually going to be seeing the show, by and large, will have never seen anything like this before — at least on this kind of scale. What kind of reactions are you expecting or hoping to get from your audience?

|

PB: |

Well that’s the fun part! But I hope I get well received, and in the grand scheme of things, this is an art show, so one hopes that maybe somebody cares enough to buy one of your prints. Mostly, if somebody outside of the community bought one of my prints I think I’d be flabbergasted — the fact that it would mean that someone who’s never seen this before appreciates the print enough that they want to put it in their collection. There are collectors out there who buy Joel Peter Witkin’s stuff — and that’s a guy that’s so popular that he’s fueled by people who want to buy art — and if I’m ever compared to him or held in the same regard as him, I’d be incredibly flattered. Maybe that’s a little bit of what I’m after. My biggest fear, though, is just having people dismiss it, and walking out of the room and go, “Ahh! Yecch!” and ignoring it. Most of what I’m hoping for is that everyone takes a really hard look at everyone that I photographed, because everyone that I photographed is a peer and a friend — they’re blood to me — and I want everyone to take a really good look and see inside of each person’s experience.

As well, I can be a businessman and say, the truth is, there’s been a lot of advertising and a lot of people have been invited to this show, and maybe this will spin off and it’ll be a catalyst in my commercial and editorial career, shooting for magazines and advertising and that sort of thing. Or, it could be that I become a collectible, which is what I’m really hoping for. One of my biggest concerns right now is that my prints will just turn into Christmas presents for everyone.

|

BME: |

How natural was it to choose suspension as the subject for your first major show?

|

PB: |

“I didn’t want to have anybody that was totally nude, because then I’d hear, ‘Hey, did you see the penis?’ and that sort of thing — ‘Did you see the guy with the penis hanging from hooks?’”

|

It’s something I’ve been working on for a long time; I started shooting it about three years ago, and it was more that I just wanted to document it — I figured that I’d start seeing what I could turn this into. I’d never actually photographed a suspension before and I actually thought, “I do suspension, I don’t photograph it; I don’t do it just to take pictures of it, I do it because it makes me feel good.” Which is not to say that I didn’t have lots of opportunities to photograph it, but there were few and far between that I ever did take. More often that not, I ended up setting it up for other people to take photographs rather than me taking them myself, and then one day a light went off in my head that said, “You know what, you’ve actually got to start making this look pretty.”

I was looking at other peoples’ documentation of suspension and I wasn’t thrilled with it — it’s not that I wasn’t happy with it, but I just wasn’t overly impressed, so I thought, “I think I can do better than this.” So I started doing it, I started documenting it, and eventually I started getting this body of work together, and I thought, “Well, I have to turn this into a show.” I basically brought this all to Bob Carnie — the one who printed and is in charge of my show — and told him what I wanted to do, and he said, “Okay, I’ll help you, but come back when you have thirty more people photographed.” At the time I only had ten people photographed, but he told me that we were going to launch this, we were going to make a big show and a big deal out of it — that because it was so much a part of me, this was what I should be doing as a show because it was what I knew.

My first show is based on suspension because it’s what I’ve been working towards turning into a big art show for so long, and the eventual plan as well is to keep shooting them — to never stop, and to keep producing and working on different themes other than just the Rhode Island SusCons, trying some experimentation, trying to meet some new people, and maybe turning it into a book or something once I have a few hundred subjects in my library.

|

From Phil Barbosa’s Ascension

BME: |

Was the whole show shot in Rhode Island?

|

PB: |

Yeah, all of Ascension was shot in Rhode Island over three SusCons, and it’s almost all been shot in the same three rooms I think. The overall look is pretty much the same though — I had one unifying theme, so I picked one style of lighting that I thought worked really well. I picked that lighting, primarily, because with suspension you have peaks and valleys that come out of peoples’ bodies, but it’s not like you’re just lighting somebody’s body — you want to light it for the whole feel and the different textures that are created when you pierce the skin and suspend someone. The entire landscape of their body is transformed, so I thought I had to make the lighting really accentuate everything — not so much that it made it look scary, but so that it made it look right. I wanted to capture all those elements, but still have it be relatively soft lighting so that everything still looked nice — I didn’t want someone to come look at it and go “AH! That looks like it hurt!” because the lighting is so hard, sharp and intense. But again, that’s my thing: The lighting and exposure. If you’re not doing it right, the images aren’t really worth anything.

|

BME: |

Well, looking at your work, as far as images of people hanging from hooks go, they really look as gentle as possible.

|

PB: |

Well so are the people that are hanging, right? They’re not bad people; [other photographers may have] just wanted to make them out to be big and horrible, and I could have easily done that — that would have been a really easy card to play — but I don’t think I could have had anyone walk into the gallery and, when they took a look at the walls, feel compelled to view them for more than ten seconds. I didn’t want my opening to end with people screaming and covered in red wine because they were convulsing from looking at the images; I wanted a sense of compassion, and I wanted people seeing the pictures to think to themselves, “Oh, this person looks like they’ve gone somewhere else” — well maybe they have, but I want you to go with them too, not just look at it.

|

BME: |

How satisfying was it to be able to integrate two of your biggest passions — photography and suspension — into a single body of work?

|

PB: |

It’s fulfilling, but there’s always a lot of stress when you’re working. Every time I go to work at a SusCon there’s a bit of stress, and every time I have to produce a big shoot there’s a lot of stress. But for me, when you do marry the two together, it really does give me a sense of self-satisfaction, and some of the great people that I’ve worked with made it even better — having worked with expert riggers like Evan, Emrys, Oliver — especially Oliver, the guy is unbelievable in the way he can visualize rope and rigging and everything and create these moments. That, taken in conjunction with the photographs themselves, gave me such a huge sense of self-satisfaction because it made it really start to seem like it was more than just a guy hanging from hooks, and that really became evident when the show was printed. A couple days ago I was at the framer getting everything flattened and pressed, and as [the prints] were coming out of the hot-press, I was looking at these things and it was just incredibly satisfying; I was thinking, “You know, this is my first show, and this is fiber-based paper, and this is my photography, and these are people that I helped suspend”, so I had my hand in everything right down to the end of this show — I’ve taken on the task of learning how to do framing so I can have my hands stuck in that portion of it as well. So combining the two is very satisfying, but mostly it’s all come at the end when I could see the finished product.

|

From Phil Barbosa’s Ascension

BME: |

What’s the format of the art itself?

|

PB: |

There are 20 prints, all 16" by 20", fiber-based, printed slightly dark — all based on the ideas of Bob Carnie, the master printer who sat with me for a lot of hours and volunteered his time, which is usually $60/hour for art show consultations, for free. He was just really into this project and wanted to be a part of it and sat there and said, “This is going to be printed dark like this and we’re going to tone it like this and do it like that”, and just gave me his thirty years of experience. And it was quite something — Bob’s an amazing man, and he’s definitely one of those people who never takes any bullshit from anyone, he doesn’t talk bullshit, and it was just one of those things where if he said something, that was it.

| |

“He did all the printing and proofing for every run of ModCon shooting, and I became known as the guy who’d come in once a year with a pile of film — because the rest of the time it’d be one or two rolls from people here and there — and Bob always remembered my name. I’d walk in and he’d say, “Mister Barbosa! You have more of that weird shit for me today?” or, “Got any more of those naked men with the weird genitals?” — but what I found out after was that Bob never processed any of the stuff himself, he always had one of his high school co-op students do it! Which is even funnier, because one of them still works there right now, and he’ll never let me live down the fact that he was 16 years old and printing contact sheets of many adult penises.”

- Phil Barbosa, on Bob Carnie of Elevator Studios

|

|

|

I wanted everything simple though — I wanted standard museum mattes, cotton color, and standard black frames — I wanted everything to look very simple and very elegant. I had people telling me I should have had them hanging from the ceiling on stretched frames with rings and hooks and all sorts of ridiculousness — and if it was a decoration piece or I had them hanging in a goth bar or something like that, then sure, maybe. But I’m trying to be considered a serious artist, and I’m trying to bring this into a different light — I don’t want everyone to look at them and cringe. I want people to see this and I want them to react, and however they react is fine, but I want at least half of the people to go in there and look at this and just seem like they’re looking at something really pretty — like they’re seeing more than just a person hanging; they’re seeing emotion and they’re seeing life and they’re seeing that moment I mentioned, where you see someone’s head turn completely around. I want them to walk out of the gallery with that same feeling, that their heads have been turned completely around, and that they’ve been affected by seeing my work — the same way someone’s affected by a suspension.

|

BME: |

How many shots did you narrow down your top 20 from? What were your criteria for inclusion in the show?

|

PB: |

I had about 40 people photographed, and the stuff that got edited first were things weren’t exactly the right lighting or were out of focus, or just didn’t have particularly the right feel — if anyone looked like they were in any kind of agony where you could see it in their face — too much wincing, tearing up too much — I took them out of the show immediately, which cut it down to about 30 people. From there, all the nudity and all the women got pared out. Now, before anybody jumps on me because I took nudity out and because I took women out, it was a conscious decision on my part, primarily because I didn’t have enough women photographed, and what would happen if I did a 20-print show and I only had two women out of 20 people in the gallery? One or two things: If you have a woman doing a suicide suspension, for example, if she has no top on, it does unfortunately turn into a sexual thing, and when someone comes in and sees a half-naked woman, it’s going to turn into, “Did you see the tits on her?” — and that’s all I’m going to hear. Not from everybody, mind you, but there is going to be a certain contingent that is going to react that way to nudity. What I’d also end up hearing is, “Oh, that poor girl, I can’t believe somebody would hurt that woman like that.” So I didn’t have enough women to balance out the show — I was hoping to have had more women, but it didn’t happen. That said, I think the next goal is to start doing a show that is either all women or has a strong incorporation of females into it.

But again, I didn’t want to have anybody that was totally nude, because then I’d hear, “Hey, did you see the penis?” and that sort of thing; “Did you see the guy with the penis hanging from hooks?” — because I’d only have one or two guys suspending naked, and no one would ever be able to leave that alone. I tried to keep everything as clean as possible — yes, most of the guys are in their boxers, but it’s what everyone felt comfortable in. When you’re shooting at SusCon, you can’t really tell everybody what to do as far as how it’s done and how everything is set up, but for future shows I’m going to be shooting more towards, “This is the goal, I need help, this is how I want everything to look.”

|

BME: |

What work and planning went into actually producing content for Ascension?

|

PB: |

A lot of traveling back and forth from Providence, and if it wasn’t for Frank Meglio (IAM:frank_prov), Emrys Yetz (IAM:along those lines), all the guys from Rites of Passage and iHung, the few remaining members of TSD, Mayhem, everyone who was involved — I don’t think I ever would have been able to do this. Especially Frank, because Frank has been the equalizing force in making sure that I got there, in making sure that I was documenting this experience, and in making sure that everyone knew that I was the most important camera in the place and to not get in my way. Working as staff at the SusCons has helped a lot too though, because Frank really takes care of his staff, but as far as planning? Packing gear as small as I could and lying to the border guys about where we’re going and what we’re doing. But once we were there, most of the planning in the early stages was just figuring out how I wanted to light these and how I wanted to set them up, and making sure that everything was consistent right across the board.

|

From Phil Barbosa’s Ascension

BME: |

What about planning the actual exhibit?

|

PB: |

Well fortunately for me, Bob Carnie also owns Elevator, so getting space at the gallery came pretty simple; originally when I talked to him about getting a show, I told him I was going to shop it around to some of the more “bad boy” galleries in Toronto and see if somebody was interested, and he pretty specifically told me that he was offended that I hadn’t asked him already to go into his gallery, and he followed that up immediately by offering me a spot in the Contact space for the entire month. I got that spot over many other people, and I was really fortunate to be invited. But as far as planning goes, it’s just a lot of work mostly trying to get the media’s attention and getting them to my show.

|

BME: |

What will make Ascension a success for you?

|

PB: |

A big party, lots of happy people, a couple of red dots on the wall — red dots indicate a sold print — and maybe some emails from people saying, “I really liked your show.” The biggest thing for me is to get positive feedback from people, in hopes that eventually I might start to get recognized more and eventually might be able to make more of a living as an artist. I realize, that it’ll be a long road before everything starts to happen — but I think Ascension being a success is mostly based around people remembering my show. Like everything in photography, you’re only as good as the last thing you did, and if I leave a good impression on everyone who walks in the building, they’ll never forget it — and then I’ve definitely done something good. I want to leave one hell of an impression on people, and I know that if I get a lot of fan mail in the end, or I get a lot of signatures in my little notebook, then I’ll know that the show was a success. And not just the show as in the opening, but also the show itself.

The other way it’ll be successful is if I get people coming back to look at the work after the opening — people that went to the opening that had to come back a second time and see it without a crowd because they wanted to really look in and see into it.

* * *

|

A recent acquisition from the illustrious, high-profile world of low-budget

sporting-goods photography, Jordan Ginsberg is a Toronto native. Born

affiliated to the Levi tribe, Jordan renounced his religion shortly before

his Bar Mitzvah but still believes he is entitled to a role in the liberal

Jew-run media and sees BME as an ideal stepping stone. Votes left, throws

right.

Article copyright © 2005 BMEZINE.COM. First published April 20th, 2005 in La Paz, BCS, Mexico. Requests to reprint must be confirmed in writing.

|

I’ve been moderately successful, but it’s up and down. With weddings and portraits, you’re only as busy as what the industry dictates as far as how much people want to spend that year. Recently, it’s become that in the wedding and portrait industry — at least in Toronto — people aren’t spending what they used to on higher quality work. Often with wedding photography, people just assume that a picture is a picture is a picture, and if they can pay $500 to have somebody there with a camera, then that’s fine — but that’s really hurting people like me who are trying to produce really high-quality work from start to finish. I’ve had to turn away a lot of clients who come in and say, “Well, I only have this much money, and I want you to shoot my wedding, and I want you there for 12 hours”, and I say, “Okay, well that’s fine, but I want $2,500” or whatever it’ll cost me to be able to do it properly — and then they turn around and say, “Oh, well my uncle’s got a digital camera, I think he can do it for $500.” You know, if you want a nice car, you pay for it — unfortunately that’s not always the way people think in this business. I mean, if someone walks into a Mercedes dealership and says, “I don’t really want to spend that much money on that brand new car there, but so-and-so over at the Toyota dealership offered me one for $20,000”, how can you compete with that?

I’ve been moderately successful, but it’s up and down. With weddings and portraits, you’re only as busy as what the industry dictates as far as how much people want to spend that year. Recently, it’s become that in the wedding and portrait industry — at least in Toronto — people aren’t spending what they used to on higher quality work. Often with wedding photography, people just assume that a picture is a picture is a picture, and if they can pay $500 to have somebody there with a camera, then that’s fine — but that’s really hurting people like me who are trying to produce really high-quality work from start to finish. I’ve had to turn away a lot of clients who come in and say, “Well, I only have this much money, and I want you to shoot my wedding, and I want you there for 12 hours”, and I say, “Okay, well that’s fine, but I want $2,500” or whatever it’ll cost me to be able to do it properly — and then they turn around and say, “Oh, well my uncle’s got a digital camera, I think he can do it for $500.” You know, if you want a nice car, you pay for it — unfortunately that’s not always the way people think in this business. I mean, if someone walks into a Mercedes dealership and says, “I don’t really want to spend that much money on that brand new car there, but so-and-so over at the Toyota dealership offered me one for $20,000”, how can you compete with that?