People are angry at Rob Spence. It’s April Fools’ Day, and his prank of choice was to make a morning post on Facebook that a battery exploded in his eye and that he was in the emergency room awaiting…well, whatever sort of treatment such an accident requires. But he’s quick to shift the blame.

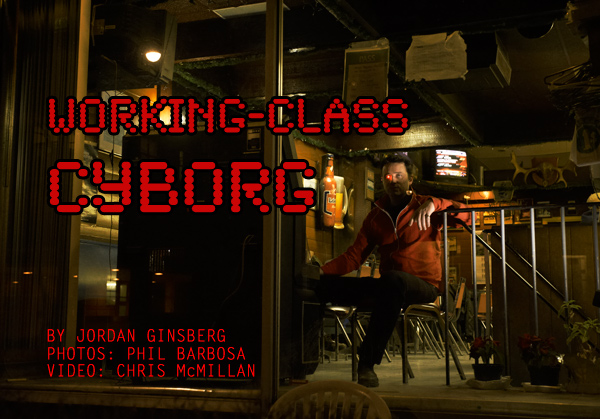

“That was your idea,” he scolds Kosta Grammatis, the brilliant 23-year-old aviation electronics engineer who’s been living in his home office for the last two months. Kosta laughs him off and goes back to his dinner. We’re sitting in Harry’s (along with BME photographer Phil Barbosa), a bar near Rob’s home in Toronto’s Parkdale neighborhood. Less than an hour ago, we were in Kosta’s makeshift bedroom while he assembled a prosthetic eye for Rob—a clear, rounded silicone case housing a small red LED light—to give us an idea of the technology with which they’re experimenting. To be fair, his April Fools’ joke seems entirely plausible.

When Rob was 13, his right eye was damaged in a shooting accident on a family member’s farm. Six separate surgeries were performed over the years to repair the eye’s vision, but each time it regressed, and the eye grew larger, turned white, and became increasingly disfigured and painful. “I’ve had a doctor stick a needle straight into my eye about 10 times,” Rob says, “and I was thankful for it. Like, ‘Please stick the fucking needle in my eye.’” Several years ago, the ophthalmologist father of a friend of his told him he had to prepare to let go of his eye, and after a year and a half of deliberation and anxiety, he decided it was the right move. “It’s a hard thing to let go of a part of your body,” he admits, “but it was time for that garbage to go.” Three years ago, he finally had it removed. Now, Rob, 36, a filmmaker and videographer, wants to make good use of the vacant lot in his face: He’s trying to build a miniature video camera to wear as a prosthetic eye in the empty socket.

This is where Kosta came into the picture. He contacted Rob after hearing about his project and realizing, hey, he was more than qualified to run point on this. (Or, at least, he was no less qualified than Rob.) The two met in San Francisco while Rob was there visiting his father—Kosta, at the time, was squatting in a coop warehouse—and found they shared a similar vision. Kosta came to Canada and took up residence in the back room of Rob’s house, and the two have been teammates since, trying to devise a working prototype. The main difference between their operation and a proper lab, of course, is funding; that is, they have none.

Rob is broke, he says. His credit cards are maxed out. He borrowed $500 from his little sister earlier in the day. Plus, you know, he’s trying to build the world’s first miniature prosthetic eye camera, and now he’s pissed off a whole lot of people with this April Fools’ stunt. Now, thinking about the LED he was just wearing in his eye, he realizes the whole joke could have thoroughly backfired. “Imagine if the battery really had blown up in my eye tonight after I’d cried wolf on Facebook?” he says. He remembers, though, that his brother-in-law had a good point. “Do people think if I’d really blown my eye apart, and I was sitting in the emergency room, that I’d be talking about it on Facebook? It’s come to the point where people feel like sitting in the E.R. with my eye bleeding profusely is a perfectly reasonable time to update my Facebook status.”

Except, if anyone were to do such a thing, Rob would be a prime candidate. Ever since the initial accident, he’s developed a talent for drawing attention to himself. “When you’re a kid,” he says, “and you have a dramatic accident, it’s like the origin of a super hero. When I came home from the hospital, I’d turn to my little siblings and say, ‘My eye really hurts, can you get me a glass of lemonade?’ And they would actually fuckin’ get it for me.”

The Tiny Tim act only lasted so long, though, and, with his current project in mind, he realizes investors won’t be refilling his glass if all he has to offer is a sympathetic story. This is the part of the job Kosta calls “skepticism management.” According to Rob, the typical engineer mindset is that a person should build a prototype of an invention first, be modest about what he’s created, and then start showing it off to people. Not him. He’d rather create excitement for the project among the people working on it, the people expecting and, ideally, the people financing it.

“I’m all about the sizzle before steak,” he says, grinning, “because sizzle can buy you steak.”

Kosta perks up at this. “We shouldn’t even be building anything,” he says. “You don’t even need me.” Kosta is equal parts easy-going, sun-kissed southern Californian and genius scientist; it’s a disarming combination. And, to be sure, Rob does need him. The pair have two working prototypes for Rob’s camera-eye, success Rob attributes largely to Kosta, due to both his technical skills and his ability to seek out the right people to do the jobs they can’t. Thus far, they’ve built devices that create wireless NTSC signals—the sort of standard wireless signal a television uses—and are now working on getting this to work in sync with a miniature camera and a battery, all attached to a printed circuit board, all of which has to fit inside a prosthetic eye.

What about what we saw earlier in the evening, though? Rob sporting a glowing red light in his eye? Does that count for anything?

“Oh,” he says, taking a draw off his scotch, “that’s just bullshit for press like you.”

“Yeah,” Kosta adds, “that’s just for your entertainment.” Right. Sizzle before the steak and all that. And all of a sudden, they’ve just driven a truck through the fourth wall. It’s an admittedly respectable sort of transparency: Phil and I thought we’d captured something unique for our article (which we had), and Rob and Kosta thought they’d done due diligence in drumming up some more attention for themselves (which they had). They’re not approaching this project like seasoned veterans of the scientific community: They’re trying to make a breakthrough on a shoestring budget.

“Can you write, like, ‘Rob and Kosta looked emaciated, as if they hadn’t eaten for days’?” Kosta asks, laughing.

“Hey!” Rob says, pointing a finger at Kosta. “You look emaciated. I look fuckin’ fine.”

In the search for funding, they scared off National Geographic by requesting $75,000; apparently, the publication thought they could achieve their goal with closer to $10,000. This is a common experience, Rob says, and one that betrays a sort of myopia. He compares it to Alexander Graham Bell’s first success building a telephone: “How much more money do you think he needed to build a robust version that worked all the time?” Even as far as video devices go, he thinks he’s being reasonable. “People tell me I’m crazy if I want a hundred grand to build the eye,” he says, “but the standard high-definition camera they shoot with on T.V. is worth about $120,000 to buy. How much do you think it cost to develop?”

So in the meantime it’s bullshit red lights for guys like me, but even stunts like that can be beneficial—that’s the sort of sizzle that earns them credibility with the cyborg culture. This, it seems, is something of a concession for Rob. Support is welcome regardless of the source, he says, but this is a segment of society with a bit of an identity crisis. Lots of people have fake eyes, so what’s the difference between a cyborg and someone who just has a prosthetic?

|

“Someone with a wooden leg is not a cyborg,” he says, “they’re a pirate. Meanwhile, I have a fucking eye patch on…but if I take off my eye patch and you see a red light, then I tap into the cyborg culture that you know and love.” This, it seems, is the extent of the difference. “That’s really what a cyborg is. A fake eye with a red light in it is different from a fake eye.”

And therein lies the problem with the amorphous definition of “cyborg.” Clothing, he says, technically makes you a cyborg, because it enhances a human’s ability to live in the world as a naked animal; the same goes for glasses, pacemakers, breast implants and any other invention people use every day that’s been welcomed into the mainstream. “It’s adding shit to our bodies within the context of popular culture,” Rob says, that makes a person a cyborg.

“That’s why we went for the Terminator eye,” Kosta admits. “It’s quickly identifiable.” But the truth, he says, whether or not he’s just trying to sell me sizzle, is that once funding comes through, the possibilities for Rob’s eye are endless. He talks about an idea for installing a laser in the socket that he could bounce off mirrors and panes of glass, and with the right piece of technology, the reverberations off those surfaces could be translated to hear what people are saying in the rooms in which said glass could be found. “We could make you a bionic eye-ear! We could have a little transmitter that transmits audio into your ear.”

Rob belches in response. One of his dreams is to be able to screen movies from his eye. “What I want to do eventually,” he says, “is walk around always shooting Breakfast At Tiffany’s onto a wall, because chicks love it. And Dukes Of Hazzard, because guys love that. That’s why I’m mutilating myself and letting Kosta stick batteries in my face—because mostly, I want people to love me.”

He’s joking, but there’s a kernel of truth there. As much as Rob doesn’t deign to treat the loss of his eye with much seriousness, he admits to the difficulties in adjusting to life after the surgery. “You don’t feel quite right,” he says, “you don’t feel like you’re as attractive as you used to be, you feel like you’re not quite the man you were. It might sound stupid, it’s not like I lost a leg or something, but you don’t feel quite as confident as you used to.

“But,” he says, “if you start to feel like you can actually be cooler by replacing the shit you lost with something better than other people have access to, then that’s when you start to feel pretty good about yourself.”

“There are already scientists working on connecting [prosthetic eyes] to the optic nerve,” Kosta says, “so imagine if, all of a sudden, having a night-vision eye was possible and available to people who were missing an eye? Wouldn’t you be like, ‘Fuck, I want a night-vision eye’?”

And so is presented a modern predicament. For years, it seemed like the ostensible purpose of prosthetic limbs was to as closely resemble the original appendage as possible. Recently, however, this has been uprooted by a focus on mimicking the function of the missing part (and, in some cases, exceeding the original’s capabilities), with aesthetics becoming a secondary concern. Now, these two paths are converging; limbs and organs that look “normal,” but that carry possibilities far beyond what the human body can accomplish in its natural form.

Rob foresees a disturbing trend. “One day,” he says, “I might have a grandkid that will actually want to remove an eye voluntarily, and I would tell that kid not to do that. But, I know that kid would just say to me, ‘Well, grandpa, you did it!’” For him, there is a significant difference between him augmenting himself because he lost something, and a person purposely chopping off a limb with the intention of “upgrading” it. He worries that what he’s doing, playing the role of “Eyeborg” and whatnot, will make people think that he thinks it’s cool to remove parts of their bodies. “Which,” he says, “it’s not at all.

“But,” he admits, “I’m open to the idea that that’s where things are going.” He goes on: “I think the main point is, how can our kids shock us? My kid could be a gay punk rocker and I’d be like, so? I don’t give a fuck. Gay punk rocker—big deal! The way they’re going to shock us is, ‘Dad, I’m gonna get a new fuckin’ hand.’ And we’re going to say, ‘Well, I’m not sure you should be doing that.’ But we’ll be the worst offenders, because we’re all in the movement. We won’t like it. Even though we’re already buying into it, we won’t like it.” It’s the duality of the conscientious cyborg: How do you balance a desire to improve your own life—and find someone to give you hundreds of thousands of dollars to do so—with not wanting to set a precedent for future activities of which you already disapprove?

But maybe this is all just so much navel-gazing without grant money in hand. Until funding comes through to ensure Rob will be able to cement his legacy as Grandpa Hypocrite, there’s still the matter of living his life as a one-eyed man—which is not without certain high points.

“When he sees other people with eye patches, they give each other high-fives,” Kosta says, laughing. This reminds Rob of Steve Fonyo (“Terry Fox light,” as he calls him), a Canadian who lost a leg and, in the spirit of Terry Fox, ran across Canada; unlike Terry Fox, however, he made it the entire way.

“Except,” Rob says, “he was a drunk, and so was his father driving the van. They made it the whole way across and he never died, but he never gets any credit. And I did an interview with him, and I asked him, ‘So, Steve, did you get laid? When you were running across Canada with your one leg, did you get laid?’

“And he goes, ‘Oh yeah.’ And then, after a pause, ‘Big time.’”

Rob isn’t quite as shameless, but he’s got what seems like a go-to maneuver nonetheless. “When you’re at a party and you’re wearing an eye patch, girls are thinking, ‘Are you vulnerable? Or are you mysterious? Or are you a bad boy? Or are you all three of those things?’” he says, cracking up the table and breaking into a snort-laugh of his own. “They’re curious, so all I do is say, ‘Well, I’m curious about what your boobs look like. This is my raw fuckin’ naked eye here, it’s vulnerable for me and I don’t feel so great about it. So, maybe it would make me feel better if you showed me your breasts.’ And inevitably, it’s a fairly good deal.”

Kosta, the sidekick, is picking up life lessons. “You have to have some kind of emotional experience,” he theorizes, “because they’re going to have a unique emotional experience.”

“That’s the thing,” Rob says. “If you’ve got an eye out, and you show someone the flesh inside, it’s almost like you’ve got a pussy in your head. That’s what it feels like. They always want to see it. ‘Pull your patch aside and show me what’s in there.’ And when I do, it’s the same look as a 13-year-old boy who wants to see a pussy for the first time.”

All photos © Philip Barbosa / BMEzine.com 2009. Video is coming soon!

Visit the Eyeborg project online at EyeborgBlog.com. Rob can be found here, and Kosta can be found here.

Please consider buying a membership to BME so we can continue bringing you articles like this one.