(Editor’s note: This article will be published in the summer 2012 issue of The Point, the publication of the Association of Professional Piercers. James Weber the article’s author, have given BME permission to publish this article for the continued education of professionals and body art enthusiasts. Enjoy.)

Late last February a rather curious news story made the rounds on Facebook and other social media sites and pop culture blogs. Various publications1 reported on an article2 about a project from Georgia Tech, one that enables a person with quadriplegia to control a wheelchair through the movement of the tongue by moving around a magnet worn in a tongue piercing. Piercers everywhere were sharing, reposting, and reblogging the article in a variety of places—including on my Facebook timeline. Fortunately, this was not news to me, as I’ve had the unique opportunity to be involved with the project as a consultant for several years. But after a dozen piercers forwarded me the article I realized it was time to write about my experience with the clinical trials of the Tongue Drive System.

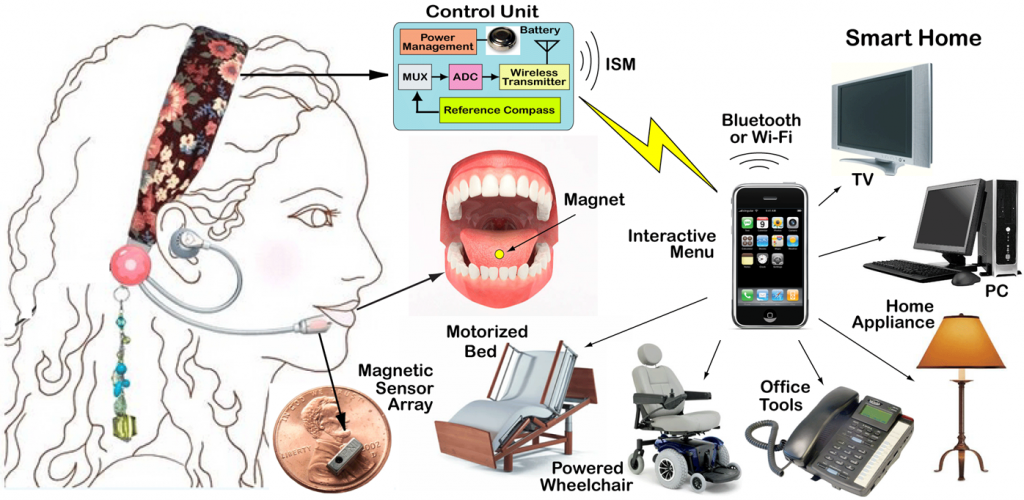

In late October of 2009 I was contacted by Dr. Maysam Ghovanloo, Associate Professor at the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology. Over the phone he explained the project that he was working on, titled in the research protocol Development and Translational Assessment of a Tongue-Based Assistive Neuro-Technology for Individuals with Severe Neurological Disorders. Simply, this is a system that allows persons with quadriplegia to perform a variety of computer-aided tasks—including operating their wheelchairs—by changing the position of a small magnet inside their mouths. The magnet’s changing position is monitored by a headpiece that looks like a double-sided, hands-free phone headset.

His team had, at that point, experimented with different ways to attach the magnet to the tongue with varying degrees of success. Adhesives were only effective for very short periods, and the idea of permanently implanting a magnet into the tongue was not considered a workable alternative.3 This left a third option suggested by Dr. Anne Laumann: attaching a magnet to the tongue with a tongue piercing.

He then came to the reason for his call: he asked if I would be interested in being involved in the clinical trials as a member of the Data Safety Monitoring Board. As I listened to him describe the details of my involvement, I thought about the incredible places my life as a piercer—and my job as an APP Board member—have brought me. I enthusiastically and without hesitation said “Yes!”

(Note: The article is pretty lengthy, so we’ve put a break here to same some space. Click the Read More button to continue)

For those not familiar with clinical trials (and I was not when I initially agreed to be involved with the study), the Data Safety Monitoring Board (or DSMB, alternately called a Data Monitoring Committee) is a group of experts, independent of the study researchers, who monitor test-subject safety during a clinical trial. The DSMB does this by reviewing the study protocol and evaluating the study data, and will often make recommendations to those in charge of the study concerning the continuation, modification, or termination of the trial. The inclusion of a DSMB is required in studies involving human participants as specified by the Common Rule,4 which is the baseline standard of ethics by which any government-funded research in the United States must abide. (The clinical trial is sponsored jointly by both the National Science Foundation and the National Institute of Health, but nearly all academic institutions hold their researchers to these statements of rights regardless of funding.)5

I was excited to be part of the project, and the following May I received the full details of the study. The clinical trial was to be performed in three phases, with three sets of participants. The first involved ten able-bodied individuals with existing tongue piercings. These participants were to test the hardware and software created by his team and to quantify the ability of those participants to operate the wheelchair with the specially-designed post6 in their tongue piercing. The second group consisted of ten able-bodied volunteers without tongue piercings. These participants were to be pierced, given time to let the piercings heal, and then monitored operating the Tongue Drive System. The third group of participants was to be a selection of thirty people with quadriplegia—without existing tongue piercings—who were to be pierced and then monitored while the piercing healed. Afterward, they were to be evaluated on their ability to operate a computer and navigate an electric wheelchair through an obstacle course using the magnetic tongue jewelry.

The study was to be conducted in two different locations: in Atlanta, at the Georgia Institute of Technology and the Shepherd Center; and in Chicago, on the Northwestern Medical Center Campus and at the Rehabilitation Institute of Chicago, with half of the participants in each phase of the study coming from each location. (Five from each city for the first two phases, fifteen from each for the last.) Drs. Maysam Ghovanloo and Michael Jones were to oversee the trials in Atlanta, and Drs. Anne Laumann and Elliot Roth were to oversee the trials in Chicago.

The DSMB charter specified the eight people who had been drafted to be part of the DSMB: The board chair is a professor of rehabilitation science and technology; one member is a director of a rehabilitation engineering research center; one a professor of rehabilitation medicine. There are two M.D.s: one a neurologist; one an associate professor of dermatology; two biostatisticians (one acting as study administrator); and me. Also included in the documents sent was the full study protocol. This document outlined the finer points of the study, including the protocol for tongue piercings to be performed by the doctors involved with the study. The email also specified the possible times of the first meeting of the DSMB, to be conducted via conference call.

As I participated in the conference call several weeks later it was hard not to feel I was out of my element. While I routinely lecture at several local universities, it’s been quite a while since I’ve been in academia. But I soon realized I was not there for my academic credentials but for my position and experience—and as a de facto authority on piercing. This I could do.

During that first meeting I expressed the concerns I had about the piercing protocol, specifically about physicians performing the piercings—physicians with little or no experience doing so. “Do any of the members on the research team have prior piercing experience?” I wrote. “Even though it is not a complicated procedure, it is better for doctors who are involved in this task to have prior experience with tongue piercing.”

I was told that the physician overseeing the piercings in Atlanta had performed at least thirty tongue piercings in his private practice. And although Dr. Laumann—who was responsible for the tongue piercings in Chicago—had no prior piercing experience, she had conducted extensive research on piercing and tattooing7 and had often observed professional piercers at work. (Furthermore, she is considered an expert among dermatologists in the field of piercing and tattooing.) While my concerns were addressed, I do remember feeling hesitant at the close of that meeting.

The second DSMB meeting was held six months later, in December of 2010. At this time the results of the first and second phases of the clinical trial were to be discussed. Before the meeting I was given information about the second study group and about the tongue piercing method performed at the Chicago location—and including images from both locations. From the images provided, I was concerned that the piercings performed by the physicians looked as if they were done by first-year piercing apprentices—which, in a way, they were.

Of the twenty-one study participants who received a tongue piercing, five were noted as complaining about the placement of the piercing, and three piercings resulted in embedded jewelry. Based on the photos I guessed this was because either the piercing had been placed too far back on the tongue or the length for initial jewelry was improper—or both. I pointed out to the committee this left only about 60% of the subjects who were both comfortable with the placement of the piercing (at least enough to not state the contrary to researchers) and who did not have problems with embedded jewelry. I stated I thought this was far too small a percentage to ensure the well-being of each research participant. Even though it was outside my role as a DSMB member, I further stated the results of the study may be affected by the improperly placed piercings, as more than a few of the study participants had taken out their jewelry and dropped out of the study within a few days of being pierced, saying they were either unhappy with the placement or found the position of the piercing uncomfortable.8

I went on to express concerns about the piercing protocols and to question whether piercers could perform these procedures instead of physicians. Unfortunately, I was told the parameters of the study, and the rules at the medical centers where the piercings were being performed, did not allow non-medical professionals to perform the piercing procedures.9

Despite my concerns, my suggestions and criticisms were well-received. Dr. Ghovanloo agreed to re-evaluate the piercing protocol and I offered him whatever help he needed. Most importantly, I got the impression the two doctors performing the piercings were somewhat humbled by the experience. While there was no doubt that these physicians have anatomical knowledge and surgical experience that far surpasses mine, they were quickly realizing this didn’t make them proficient piercers.

Several months after that conference call, I had the opportunity to finally meet Dr. Ghovanloo in person. The quarterly meeting of the APP’s board of directors was scheduled in Atlanta in February of 2010, and Dr. Ghovanloo arranged for me to meet some of the trial staff at the Shepherd Center. I had the sense he was excited as well, and he also arranged for the physician doing the piercings during the clinical trials in Atlanta to be there: Dr. Arthur Simon. As I was at a board meeting with Elayne Angel (the APP’s then-Medical Liaison, current President, and resident expert on tongue piercings), I asked about having her attend as well. He readily agreed.

When Elayne and I arrived we were greeted by Shepherd staff member and study coordinator Erica Sutton, and we were soon led to our meeting with Dr. Ghovanloo and Dr. Simon. Compared to the necessary formality of the DSMB meetings, it was a friendly and relaxed meeting. Dr. Ghovanloo and his colleagues were somewhat starstruck by Elayne (she often does that to people) especially since her book, The Piercing Bible, was used so extensively in drafting the trial piercing protocols.

As we talked about the clinical trials, it was hard to not be affected by Dr. Ghovanloo’s enthusiasm for the project. We spoke at length about the issues the doctors encountered when performing the piercings. Doctor Simon in particular was humbled after his experience. “How do you hold those little balls to screw on?” he asked at one point during the several hours we met, a little exasperated and only half joking. I can’t speak for Elayne, but I left with an immense respect for Dr. Ghovanloo, his staff, and the whole project. I also left with the impression that they had a lot more knowledge of—and a little more respect for—what we do as well.

Since that time, stage three of the clinical trials has already taken place. I’ve been informed by Dr. Ghovanloo that the third and final meeting of the DSMB will be scheduled in the coming weeks. In fact, trials are being planned using a new prototype that allows users to wear a dental retainer on the roof of their mouth embedded with sensors to control the system (instead of the headset),10 with the signals from these sensors wirelessly transmitted to an iPod or iPhone. Software installed on the iPod then determines the relative position of the magnet with respect to the array of sensors in real time, and this information is used to control the movements of a computer cursor or a powered wheelchair.

I’m looking forward to hearing when the project is out of the trial phase and more widely available to all who can use it. When that happens, I’m sure I’ll be hearing from Dr. Ghovanloo—and seeing the news again posted on Facebook.

More information about the current trials can be found on the Shepherd Center’s web site: http://www.shepherdcentermagazine.org/q3_11/#/feature2/

Links:

1 http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-02/21/tongue-drive-system, http://news.discovery.com/tech/tongue-drives-wheelchair-120222.html#mkcpgn=rssnws1, http://boingboing.net/2012/02/24/tongue-piercing-steers-wheelch.html

2 http://www.gatech.edu/newsroom/release.html?nid=110351

3 Unlike implants under the skin, the tongue has no “pockets” in which to encase a foreign object, and there was also concern about the need to remove the magnet for surgeries and MRIs.

4 http://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/humansubjects/commonrule/index.html

5 The history of research ethics in the country is simultaneously fascinating and shameful. Most of the modern rules now in place concerning clinical trials in the U.S. are as a result of the public outcry over the Tuskegee Syphilis Experiment, a study that ran for four decades, from 1932 and 1972, in Tuskegee, Alabama. This clinical trial was conducted by the U.S. Public Health Service and was set up to study untreated syphilis in poor, rural black men who thought they were receiving free health care from the U.S. government. The study was terminated only after an article in the New York Times brought it to the attention of the public. More information about the history of research ethics can be found here: http://research.unlv.edu/ORI-HSR/history-ethics.htm

6 In one of my early conversations with Dr. Ghovanloo I gave him the name of several manufacturers who I thought would be willing and/or able to make the jewelry needed for the trials. Barry Blanchard from Anatometal came through by manufacturing special barbells with a magnet encased in a laser-welded titanium ball fixed on top. Blue Mountain Steel also donated the barbells and piercing supplies for the initial piercings.

7 Dr. Laumann has co-written several published papers on body piercing and tattooing. The most recent is titled, “Body Piercing: Complications and Prevention of Health Risks.”

8 Dr. Ghovanloo and the other physicians had suggestions for the reasons for the high dropout rate among healthy subjects. In response to an early draft of this article, he wrote, “We simply lost contact with a few subjects after piercing, and cannot say for sure what their motivation was in participating in the trial and consequently dropping out after receiving the piercing.” Dr. Laumann, commenting on the Chicago site, wrote, “We prescreened thirty-two volunteers. Ten of these were screened and consented. Three of these were ineligible due to a short lingual frenulum, or ‘tongue web.’ This would have made the use of the TDS impracticable and for research it would have been considered inappropriate to cut the lingual frenulum. We pierced seven subjects and—you are correct—our first subject dropped out related to embedding of the jewelry and pain on the first day. After that we were careful to measure the thickness of the tongue and insert a barbell that allowed for 6.35 mm (1/4 inch) of swelling. Otherwise drop-outs came much later during the TDS testing phase related to scheduling and unrelated medical issues. One of the subjects, a piercer herself, was particularly pleased with the procedure, the tract placement and the appearance.”

9 Though the protocols did not allow the procedure to be conducted by non-medical personnel, Gigi Gits, from Kolo, was present during one of the phase-two health subject’s piercings and Bethra Szumski, from Virtue and Vice, was able to offer advice at the first phase-three piercing session in Atlanta.

10 Dr. Laumann: “The problem with headgear is that it needs to be removed at night, which means that the disabled individual cannot do anything in the morning until the headset is replaced and the TDS recalibrated. With secure intra-oral sensors, recalibration will not be necessary in the morning, nor will the sensors slip during use, which gives the wearer a great degree of independence. Of course, a dental retainer takes up space in the mouth and this may be difficult with a barbell in place.”

Help out the youngest member of the BME family. Get a limited edition 2012 BME Classic Logo t-shirt. Read all the details here.