CLASH: This is Omo Valley |

The urge to create, the urge to photograph, comes in part from the deep desire to live with more integrity, to live more in peace with the world, and possibly to help others to do the same.– Wynn Bullock

Recently BME had the opportunity to attend the opening of Liam Sharp‘s gallery show CLASH, being hosted at the Alliance-Francaise at 24 Spadina Road in Toronto (a two minute walk north from Spadina Station for TTC riders) — the show will continue there every day until January 10th.

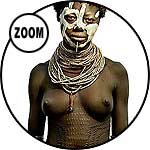

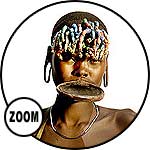

The show featured photographs from his very recent trip to inner Ethiopia where he had the opportunity to photograph members of the Hamer tribe and others around the Omo valley that still practice ancient forms of body modification. We managed to pull Liam aside for a few minutes at the show and talk to him about his experiences.

BME: The thing that really surprised me is that you could still photograph activities like the big lip stretching — when I see it in books, it seems like it was disappearing forty years ago, but these are young people with these modifications. Was it hard to find them?

Liam: The reality is that there are very few areas still doing these things. It’s more and more difficult. I was just talking to someone that lived in Africa and he said that twenty, forty years ago you could just go outside the city and there’d be tribal peoples…

But even now, one thing you have to remember is that these cultures, these countries, are still extremely tribal. In fact, their governments are biassed in terms of tribes…

BME: As in for them, or against them?

Liam: Well both… The politicians represent certain tribes, so they’re slanted one way or another. That’s why there are coups and all these political problems — because the politicians really only protect the tribes they’re from. The tribes are identities or countries in and of themselves.

BME: With their own languages…?

Liam: They have their own languages a lot of the time, and also there are traditions you can see. There are three predominant tribes in this particular show — I visited about seven in all, and there are maybe fifteen in that one area. The Omo Valley region might be two hundred and fifty square kilometers. It’s not a huge area.

BME: How large are the individual tribes?

Liam: The Hamer tribe is about ten thousand people.

BME: So large enough that you never have to leave… you can stay inside the tribe, marry inside the tribe, and so on.

Liam: I think that’s how it’s done. I was photographing a guy from the Hamer tribe, the guy with the grip on the gun —

BME: I assume those are their guns? You didn’t ask them to pose with them?

Liam: No, no, of course not.

So I told him we’re going to this village in Oromati, and he said, “there’s no way I’m going there, if I step foot in that village, I’m dead!” since the Oromo are fighting the Hamer. The territories are extremely well defined, and they’re all kind of land-locked within those territories.

BME: They’re agricultural peoples?

Liam: Yes, very agricultural. But the terrain is extremely arid… I will never eat fried goat meat again — that’s all I was fed out there! Cows and goats, that’s it.

BME: How did you get there?

Liam: I was really kind of shit scared going on this trip… I sort of chickened out, but it’s important to do it this way and I always do it this way, which is to hire a local guide. I hired a truck with a guy — you can’t get there otherwise. The great thing about the guide is that he’s been in that area, and he knows the people, so he can smooth things over…

BME: Is that what he does? Just brings Westerners in?

Liam: That’s what he does… but in the whole time I was there I saw maybe five Westerners. So I’m not the only one, but there are very few… The others were there just to go I think, not to take photos other than just a few clips. That was one of the problems I think — their expectation that I would just take a few snapshots.

BME: How did they feel about professional photos being taken? Why did they think you were there?

Liam: That was always a big problem because my guide was always very suspicious of me. “Why are you taking these pictures? You’re going to make money from these pictures?”

And the fact is, as you can see, it’s not about the money. For me it was about going there and documenting these people, these tribal people, the way they live, and the way they are right now. But they didn’t like it. They wanted money — that’s what it was. I had to pay them three Birr, which is about forty-five cents Canadian per image [ed note: Liam took about 5,000 photos while on this trip]. Every time I clicked the camera, I had to pay. We had a suitcase full of money and my guide would just be paying it out.

BME: Isn’t that a bit dangerous?

Liam: It is… but it’s perfectly fine. You know why? Because paying money takes everything off the table. I’m going there and I’m giving them money and it’s an exchange. I’m taking their picture and they’re getting money. So it’s OK. That’s not a problem.

There was a situation when I was in the Omorati area, and photographed an older person, and the person collapsed

Are we going to get out of this situation, I was wondering? My guide said that if the old man had died, they’d have assumed the flash of the camera killed him — that this process, which they don’t understand, has killed this person. As soon as it moves to “you killed one of us” then very soon after it becomes “why don’t we kill you?” It’s very simple.

Luckily we ran over, and I supported him, and he was OK — but we got the hell out of there real quick!

They don’t particularly like the photographers. I really rode on the coattails of the relationship of my guide with the chiefs. As soon as that started to wear thin (which happened very quickly) I had to get out of there.

BME: Did you stay with the tribes, or just sort of roll into town, do your thing, and roll out?

Liam: We had a process — eventually it became repetitive and I was worried about that. What would happen is we would come into town, talk to the chief, and pay him off. As my guide was paying off the chief, I’d set up the backgrounds, set up the lights, and then he would tell everyone we were shooting and this is what the price was, and all that. Then I would just point to people in the crowd, and they’d come and I’d shoot them. One, two, three frames, and then the next person.

BME: They were OK with that?

Liam: They were OK, but it didn’t take long before they realized this was more than someone just taking pictures. They wanted to know what we were doing, what they were for — there was a big suspicion. I’m getting it here at the gallery too — questioning why I would want to portray Africa like this.

BME: One of the overwhelming comments I’ve heard walking around the show tonight is stuff like “oh, how disgusting they look” and “that one is even more mutilated than that one!” Does it seem strange to you that someone would come to your show and then say things like that?

Liam: No, not at all… That’s the biggest problem I’m had with going to places like this in the world. Westerners always look from this perspective, and that doesn’t respect these tribal peoples’ perspective. The fact is these people aren’t Canadian, they’re not living in this environment, and they don’t have the same culture. You can’t expect them to have our values and conduct themselves — or want to conduct themselves — like we do.

People are always asking me, “how could you take a picture of someone with a gun, how could you do this?”

The fact is that is how they are. That’s their culture, and that’s how they want to be! It’s just as ludicrous for them to wear clothes!

BME: You didn’t ask them to take their clothes off and paint their faces like that?

Liam: NO!!!! None of that is acting… That’s exactly —

THAT’S — HOW — THEY — WERE!

That’s it. That’s how they were.

\

|

Earlier we’d been joined by Roseanne Bailey, an African-Canadian woman, also a photographer who had lived and worked in Africa for some time. She expressed deep and very valid concerns that perhaps Liam was producing some kind of “savage erotica” akin to early exploitation films — and that by decontextualizing his subjects he might actually be doing them a disservice (basically a nice way of accusing him of being a racist and perpetuating the sins of colonialism because of his show).

|

BME/News and Modblog highlight only a small fraction of what BME has to offer. Take our free tour and subscribe to BME for access to over 3 million body modification related photos, videos, and stories.

BME/News and Modblog highlight only a small fraction of what BME has to offer. Take our free tour and subscribe to BME for access to over 3 million body modification related photos, videos, and stories.