|

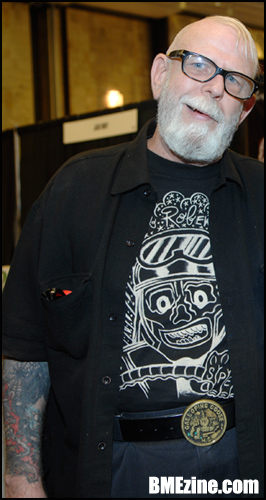

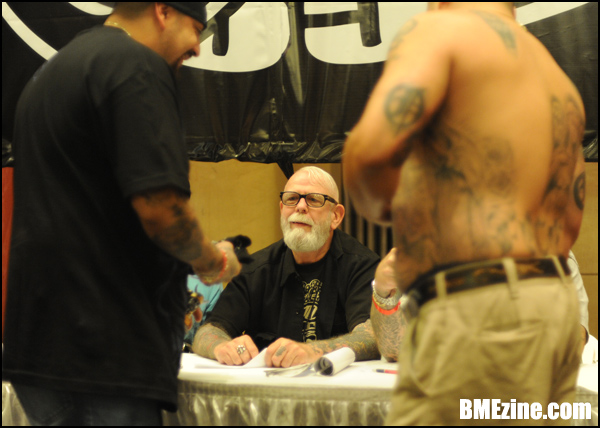

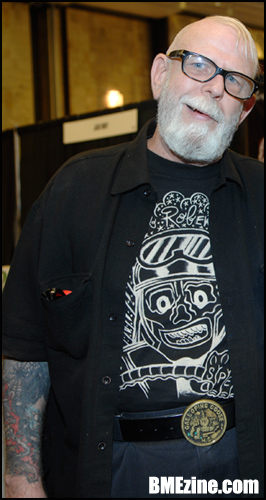

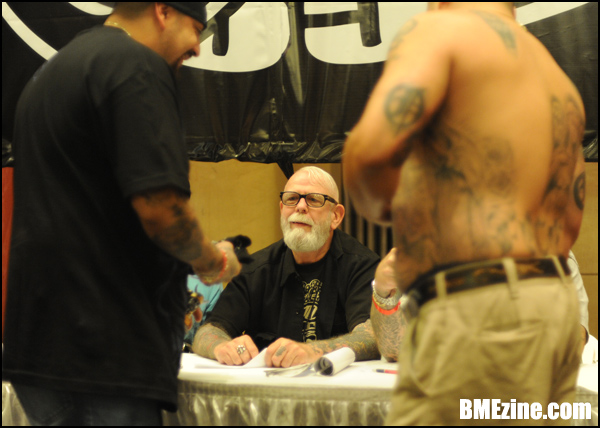

Last month, while in Los Angeles for BME’s Tattoo Hollywood convention, I was given, above all else, one specific task: to interview Bob Roberts, the owner of L.A.’s Spotlight Tattoo, whose art gallery opening that week I wrote about here. There was, of course, an element of danger. “He can be very intimidating,” people cautioned me. “Be careful what you say around him.” Though ostensibly well-meaning, these warnings were unnecessary. When we sat down to talk on Sunday afternoon as the convention was winding down, Bob struck me as a cross between Jeff Bridges’s The Dude from The Big Lebowski and John Goodman’s Walter Sobchak from The Big Lebowski: an old hippie, content with his status and the life he’s lived…who occasionally gets very, very fired up about things. (Voice-wise, though? He’s The Dude.) Drawing from his nearly 40 years of experience, we talked about his humble beginnings, shitty artists he’s known, blow job etiquette in 1970s New York, various people who deserve to have their thumbs cut off and much more. Here’s our entire conversation, edited in parts only for clarity.

BME: OK, let’s start with some procedural questions and then once we’re warmed up I’ll try to make you cry.

Bob Roberts: Alright. Can you hear me? Test, test. Is the needle going on there?

BME: We’re ready to go. So where are you from originally?

BR: Los Angeles, California.

BME: And what brought you to tattooing in the first place?

BR: Well, it’s a long story. My dad had a store at Eighth and Broadway, and he used to take me with him to work on the weekends. When I got old enough to run around, first I would go by this pawn shop that had switchblade knives that would start at one inch and would go until they were maybe over six feet. Then, they had a lot of tattoo shops, so I used to go into all of them until I’d get thrown out, and I just always loved it, man. I saw all these people getting tattooed and from a young age it just nailed me to the wall.

Later on, I was in rock and roll bands for a long time—I played the saxophone—and I was painting a lot of flash and I wanted to find a job, and I thought I could be good at [tattooing]; I loved drawing the designs. So I went to a few shops and went, “Hey! Where can I get some ink and some guns?” And they just told me to get the fuck outta there.

So, I was living in Laurel Canyon, and I was driving down the hill one day and I saw a friend of mine hitchhiking, and he had this girl with him named Truly, and she had a fringed leather jacket on with a really nice Japanese dragon done in Indian beads on there. So I inquired! I said, “Man, that’s a nice dragon, it looks like a tattoo design.” She said it was, so I asked if she did it herself. She said, “Yeah, and I’m a tattoo artist too.” This is 1973, by the way. I told her I was looking into getting some equipment and machine, and she told me she had a whole outfit she could sell me. So, I bought some machines and some flash (that I still have) and a power-pack, and that’s really how I got started.

Shortly after that, I started going down to The Pike and got my first three tattoos—my first shop tattoos—by Bob Shaw, and I told him I was interested in working there. I’d bring him stuff that I’d drawn and I’d get tattooed by him, so he gave me the ultimate challenge: bring some people in that’ll let you put a tattoo on them. Well, I was in a rock and roll band at the time and these guys knew I could draw, so I told them to come to The Pike with me to get some free tattoos—I was bringing two carloads of guys a week down there. And I did alright, you know? I guess they figured, “Well, I guess this means we have to give this asshole a job.” And they did!

BME: At what point did you branch out on your own?

BR: Well, after working for [Bob] Shaw and [Colonel] Todd, I first worked at a shop in Santa Ana where I had the honor of taking over the great Bert Grimm‘s chair, and me and Bobby Shaw worked there. I worked at The Pike for close to four years, and eventually, for the only time in 37 years, I quit tattooing for four months before going back to it after I got a job with Cliff Raven. From there, I went to work with Ed Hardy for three-and-a-half years, and then I went to New York City and opened my first shop there. It was a fifth floor walkup, where I tattooed in one half and lived in the other; that was the first Spotlight Tattoo. Then I moved back here after I got kicked out of New York.

BME: You got kicked out of New York?

BR: You know, in New York City they sell buildings like they sell houses out here [in Los Angeles]. I never knew that. I was living in a place there, and the next thing I knew my lease was up and I was going, “What the fuck, man?” I was paying $550 a month for a loft, but the guy who owned that building sold the building I was in and nine other buildings to someone else.

So, tattooing was still illegal at that time in New York City, and I wasn’t gonna live and work in the same place again, and I couldn’t afford to open a shop on the street and then get a separate place to live—plus, I was burned out on New York, so I came back here, and I went out every day for six fuckin’ months trying to find a store. On Melrose, you couldn’t rent an outhouse for less than $8,000. It’s a little different now, but back then it was in its heyday. Finally, I found a little garage next to where I am now and stayed there for nine-and-a-half years, and then I moved next door into the shop I’ve got now.

BME: So when you started tattooing, did you consciously decide what your style was going to be?

BR: No! I did what I had to do wherever I was. I broke in on biker stuff at The Pike—you’d do Harley wings every night, you’d do reapers, you’d do eagles, you’d do roses, marijuana leaves, you’d do at least one to four Hot Stuffs [devil designs] every night. All that kinda stuff, man. You work at The Pike, you’d tattoo 15 people every night, five nights a week. We had three people on the night shift and three people on the day shift, and everybody tattooed 15 people—at least 75 people a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year. I still don’t know how I did it.

So then I went on and started seeing some of Ed Hardy’s work and some Japanese work and I wanted to learn how to do that. I tried to do whatever I could—this was 1976—and I could already do the other stuff pretty well. Then I came up to work for Ed and things started changing. All of a sudden, people thought all the old American traditionalism was no good because the line was too big, you know what I mean? All the old-timers thought, “Well, that shit ain’t gonna last.” We joked and said, “Oh, this is the new thing that’s gonna replace everything?” And we were all wrong. We got on a big high horse about it, and I tried New School-style for a bit until I realized, American-style? You can’t do that way, man. It doesn’t hold up—it’s only good for certain things. But when I opened my own shop, I had to do everything that walked in the door to pay the rent. One day it’s a reaper, one day it’s a portrait, tribal, Celtic, portrait, all this different crap—I had to make a living. Some of it I was good at, some of it I wasn’t, but I did the best job I could.

But I was always best at American traditional, the stuff I did at The Pike, and I got into a comfort zone where I could take that stuff and do my own thing with it, which was really hard for me to do with the Japanese-style stuff. I worked on Japanese stuff up until a couple years ago and I just stopped doing it, it was getting too far out of my reach.

BME: How long did it take you before you realized you wanted to make a career out of this?

BR: I knew right away, I just didn’t know if I could do it. Back then, working with these old timers, you didn’t know what went into mixing ink, you didn’t know anything. Eventually, they had me in there whenever I had a day off making needles, and all the other younger artists would get mad. “Well, how come they’re showing this fuckin’ guy this stuff?” They didn’t want to teach everybody that. If they saw you painting flash? They’d look at you like, “What the fuck are you doing this for? We’ve got all the designs you need. What, are you thinking about opening a shop down the street?” Oh, they were serious! You’d ask them about mixing colors and they’d tell you, “You don’t need to know that. What, you planning on opening up? What do you need to know that for? We’ve got everything for you right here.” That’s how it was.

Somebody comes in and goes, “Oh, I want this custom—” and they’d stop them right there. They didn’t draw nothin’! If it wasn’t on the wall, they didn’t get it. They’d fire you if they saw you doing it, because they didn’t give a fuck about anything like that. If you sat there and drew for half an hour, all they saw was $200 walking out the door. If you wanted to put something custom in, you went and drew it at home, and then you had the client come back. You didn’t fuck around. Names, that’s the only thing you drew on, and you just picked up a pen and went, “Jane. J-A-N-E.” Twenty seconds. Five bucks. There was none of this fancy stuff The cheapest thing was a name, and then you’d have Hot Stuff for $12.50, eagles would start at $17.50—see, Todd said if you put the 50 cents on there, you’d get tips, he worked it all out—and go up to $36.50. I think the biggest thing they had was a peacock with grapes, and that was the most expensive tattoo, which was $101.50. We shaved their arms with straightedge razors—that’s how you could tell the men from the boys. The boys would all use their fuckin’ safety razors. If you used a safety razor at The Pike, they’d fuckin’ throw you out of there! You couldn’t fuck around with that. That took too long. Then you’d put Vaseline on their arm, and then you had an Acetate stencil that you’d use black charcoal powder on. You’d smooth it out and touch that onto their arm, and the powder would stick to the Vaseline. You had to work your way from the bottom up so you didn’t wipe the stencil off.

BME: So when you’re looking at a tattoo, whether it’s one that you’ve done or one by someone else, what makes you think, “Now that’s a good tattoo”?

BR: If it’s done right, man. First I look at the design, then I look at application, then I look at if the artist has overdone it or underdone it or done just enough. You don’t have to fuckin’ add 50 million extra rows of rosettes—no superfluous flummery, no extra bullshit. It just takes away from it.

BME: Do you feel like a lot of people overdo it these days?

BR: Yeah. The New School got all fucked up, man. They make it all limp and add all that extra shit in there—who needs it? I don’t like it. It just takes away. You’re working by the hour so you just go, “Hey, let’s add another two hours on there.” For what? For nothing. Doesn’t look good, doesn’t work.

BME: Do you think artists’ approaches have changed from when you started?

BR: People ask me stuff like that about “then and now” and where stuff is going and what do I think the new thing is going to be, but there’s something people don’t realize. If you’re a photographer, the important thing is what you’re taking a picture of, not you—if I want to be an artist, I can go buy brushes and I can go buy paper and make art. But, if I want to be a tattoo artist and nobody’s coming to get a tattoo from me, I’m not a tattoo artist. So, the future and where things are going and the approach, it’s not up to us, man. We’re secondary. The important thing is the person getting the tattoo, not me. Where’s it going? It’s going where they want it to go!

If we draw all the traditional stuff that we like and we think, “Hey, this is the shit, man!” and nobody wants it, it’s worthless. It’s taken this amount of time for people to realize that that stuff [traditional tattoos] is really what it’s all about. It’s gone all the way around with all this other garbage, and now it’s come back to where people starting to recognize that stuff again. But still, the bottom line is, somebody wants Celtic on their arm, somebody wants tribal, they should have it. They want some fucked up New School thing with 80 million colors, they should have it. I can’t tell somebody what they should get and what they shouldn’t get. I can tell them what I’m gonna do and what my capabilities are, and if you want to fuck your arm up you’ve got every right to fuck it up, but it ain’t gonna get fucked up in my place.

BME: When have you refused to do a tattoo?

BR: When I didn’t like the drawing, if I thought it was boring. I’ve had a lot of people who’ve stayed up for three days on speed and did this fuckin’ drawing they want to use to cover up five tattoos, some big fucked up treble clef, and they come in and say, “OK, here’s what I want,” like I’m a fuckin’ secretary and I’m taking dictation over here. And I go, “OK, why don’t you let me redraw this, I’ll fix it up so it looks right,” and I get, “Oh no no no, I want it just like this.” And I go, “You know what, you should have it just like you want it, and I’ll tell you what, there are five more shops down the street and you should go down there.” “Oh no,” they say, “but I want you to do it.” I say, “Well, I’m not gonna do it like this.” And I’ve had a lot of people walk out really mad at me. I’ve gotten in fights and all kinds of shit about it, but usually they come back and they thank me a couple of years later.

You’ve gotta know what to say to people, man. You can go up on Hollywood Boulevard where they’re all “experts” on every style under the sun—they’re “experts”! And once you pay them, they don’t give a flat fuck what you’ve got on your arm. They’ll sit you down, take your money and just fuck you up.

BME: So you think it should be the artist’s job to talk someone out of a design?

BR: Well, sure it should. Half these artists don’t give a fuck. Everybody’s getting tattooed now, and half of these people, they don’t give a fuck, so they go to artists that don’t give a fuck. Then, eight years later, they walk into a shop and they see what a good tattoo looks like, and they didn’t even realize they had a bunch of garbage on them. It’s sad, man, the way these people think. You go to the gas station and you get gas, you go to any liquor store and you get a pack of Camels—well, here’s a tattoo shop, you should be able to get a tattoo here! And all they’re doing is gettin’ fucked up. They got all these health department regulations and this kinda regulation and that kinda regulation—you have to be more than 150 yards away from a school and all this stuff—but on the other hand, they let some fuckin’ horrible artists just sit there and make money. That’s the sad part: so many people innocently walk in, and it ain’t rocket science, but I’ve seen just horrible stuff.

BME: What do you make of more and more young people are getting their hands and necks and faces tattooed without having substantial work done on the rest of their bodies first?

BR: Well, that’s the way it was a long time ago, but now you can’t control it. You’re an idiot if you try to, because they’re gonna get it. But on the positive side, you look around now and, Jesus, there are just so many really good artists. The degree of workmanship has just exploded in the last 10 years. There are guys who’ve been tattooing for three years and their stuff is just absolutely beautiful—a whole lot better than I probably will ever be.

BME: Do you like the convention atmosphere?

BR: Yeah, I like conventions…as long as I don’t have to work them, I like them. [Laughs] I just bring my prints and sell those. I worked at conventions for years and years and years, and then I wouldn’t do it for a while and then I’d go work at one and I’d get home and think, “Christ, what the fuck am I doing this for?” I’d work at all these conventions and I didn’t even have the money to go to them, so I had to go there and work the whole fuckin’ time. Plus, they wanna set me up in a phone booth, shine some real bright lights in my face and go, “Alright, Bob, now play us some hot jazz.” Or, “I got a spot left for Bob Roberts, I’ve been saving it just for you, right on my ass here,” the worst skin in the fuckin’ world, about the size of a postage stamp, so I’m gonna stand on my head at ten-thirty in the fuckin’ morning with a hangover and tattoo this guy on his ass because I promised him I would do it and I forgot to ask where he wanted it.

BME: Does it bother you when people want a tattoo from you just because you’re “Bob Roberts”? They’ve never seen your portfolio, they don’t know your work, but they know you’re Bob Roberts and they want a Bob Roberts tattoo.

BR: Nah, that doesn’t bother me. If they’ve got nice legs especially, it doesn’t bother me. [Laughs] I’m just like anybody else. I have to make a living. Some of these guys get so opinionated, smelling their own fuckin’ shit and backing themselves so far into a corner they can’t see their own asses—”I don’t like this” and “That’s no good,” “No blood and guts,” you censor yourself so much that you can’t swing your own fuckin’ ax. Like I said, I used to have to do everything. Now? I’ve got six other guys in there. If I think somebody can do it better than me, I’ll give it to them. People will come out of my shop with the best tattoo they can get, I don’t give a fuck who does it. Spotlight’s full of good people, and some of the worst work I ever did was when I was working by myself. Now? I’ve got hell-hounds on my chairs. I got these young fucks in there like Norm and Grant and Bryan Burke, and these guys are fuckin’ fantastic. I feel like I’m dying out over here! Throw me a fuckin’ lifesaver, you know? But it’s great, because this way I don’t have to do the stuff I don’t want to.

BME: How often do you tattoo these days?

BR: I’m down to three days a week now—down from six days a week, 14 hours a day. Now I do three days, and I can do one or two tattoos a day.

BME: And when you bring a new artist into Spotlight, what do you look for?

BR: Well, first thing, I look at their photo book, and if the guy’s got a pretty good selection, he’s good at a lot of different styles, I’ll give the guy a job. But then I’ll tell him, “You’ve gotta be more than good to be here. You can’t be a shithead, either.” The work may look good, but if he doesn’t fit in, he’s not gonna stay here. I don’t like firing anybody, but I tell them, “If you’ve got a problem with it now, there’s the door. Leave, pack your stuff and we’ll still be friends, because if I have to fire you…”

BME: Have you had many unceremonious firings over the years?

BR: Yeah. I just had to get rid of a really good artist who I found out was stealing from me. I treat my guys pretty good, man. I give them a good percentage and all that, and this guy was really a fuck. He’s lucky he just got fired. Fifteen years ago I’d have cut his fuckin’ thumbs off.

BME: What do you think of the nostalgia for the era when tattooing still seemed more “dangerous,” when it was still underground and illegal in New York and other places?

BR: I’ll tell you what, man, of all the things in New York City when I was there…you’d have a 24-hour Go Put Your Money Through A Hole And Take Your Dope spot with lines down the street and they didn’t do anything about that, but with tattooing, the minute it became illegal, nobody wanted to do it there. When I was there, there was me, there was Bruce Martin (who didn’t really do much tattooing), there was a guy named Don Singer who maybe put one on occasionally, there was Tom Devita…and that’s about all I can think of. There might have been some others—there was Mike Perfetto in Brooklyn, but he wasn’t right in Manhattan. In Brooklyn, I can’t remember if it was legal or illegal. But I mean, nobody ever bothered me. Of all the things that were illegal that went on in New York City, I mean, you could get your dick sucked down around the block for five bucks every day. You could get six girls if you wanted to spend $30 and pay five bucks a blow job, one right after the other. I’m not kiddin’, man. Nobody bothered these people, this stuff just went on. Whatever you did in your loft in New York City, if nobody complained, they didn’t bother you. And even if somebody did complain, if you weren’t chopping people’s arms off and grinding ‘em up into little bits—if there were no blood stains or torsos, the police just left you alone. I don’t know how it is now, but that’s the way it was then. So as far as any nostalgia, I don’t think there was enough of it going on then [for there to be real nostalgia].

BME: So it’s a kind of manufactured nostalgia?

BR: I think so, man. But hey, over the years, I got to be an opinionated kinda fuck, you know? And that sort of thing doesn’t matter. Like I say, the bottom line is, people put importance in tattoo artists and guys that have been around a long time, and now there are more good artists than there have ever been—they’re state of the art, they’re flying out of the roof—but still, it comes down to what people are gonna get. That’s the most important thing. Without them, we ain’t tattoo artists. You see these lovely young girls who don’t even look like they’re old enough to get in the shop and they’ve got a neck tattoo, they’ve got the back of their hand, they’ve got a dagger down the front of their chest and a skull that’s eroded and burned and spider webs—the girl’s 19 years old, for Christ’s sake. I take my hat off to them. If anybody came to me when I was 18 or 19 and said, “Hey, come on Bob, we’re gonna go to the tattoo shop and get great big fuckin’ daggers from our necks to our belly buttons,” that sort of thing was nonexistent.

BME: It’s funny, because it’s not uncommon to hear people take that as a sign of younger people being too impetuous and not thinking things through.

BR: No, listen, they’ve thought it through. It’s a saving grace. It dictates what you’re gonna be able to do in your life. God, if you get a bunch of fuckin’ tattoos like that, you’ll never be able to work in a bank, you’ll never be able to work for the FBI, and maybe people think, “Well, good, maybe that’s what I should do, then. It might save me from destroying myself.” And it does. It changes the way you look at yourself and it changes the way everybody else looks at you and reacts to you for the rest of your life.

BME: For better or worse.

BR: But see, for you guys it’s commonplace now. I remember when I got this tattoo on my forearm, what, 39 years ago? After, I went to see some friends of mine, and they were scared to fuckin’ look at me. I’m not kidding. They were genuinely fuckin’ scared of it. It wasn’t like it is now—it wasn’t popular. People didn’t do that, not the crowd of people I hung around with. They didn’t get tattoos, especially not big fuckin’ skulls on their arms.

BME: What kind of people were you friends with back then?

BR: Well, I was a hippie, and this was sort of when I was making the transition from hippie to being a musician and thinking about doing tattoos. Actually, I’d been a musician for a while and I couldn’t support myself. I always wanted tattoos and I was thinking about learning how to be a tattoo artist, toying with that idea, but also, I was just getting into getting tattooed back then. I had to think about it for a long time. The first tattoo I got was in downtown L.A., and I was working for my dad and there was a tattoo shop around there, and I just drove by the place every day for two weeks, say to myself, “There’s the tattoo shop, gonna go in?” And I’d just keep driving. It got to where I’d go to bed at night and I couldn’t sleep because I wanted a tattoo so bad, but I was afraid to get it. So finally I snuck over there when my dad couldn’t see me and I got three dots on my leg—75 cents. I never knew I’d have this many tattoos or that it’d be my profession for life or any of it. I think it came after me more than I went after trying to be a tattoo artist. I put forth all that energy trying to get machines and all that, but I didn’t really think of it as a learning experience. I was cocky. I’d go into shops and go, “Well, I can draw better than that.” And I could. Just give me a machine, you know? Just give me some guns and some ink.

Every day though, I thank my lucky stars that I broke in with Bob Shaw, Col. Todd—that foundation has helped me through it all. People who don’t get to break in at a shop like that, where they don’t get to learn how to shade a panther, they don’t learn how to do a pair of Harley wings, they don’t have that foundation, I can see it in their work that they don’t know how to do that stuff. Or they fuckin’ New School it all up, just make it a bunch of limp fuckin’ crap and I look at it and say, “Oh, I see…can you do a real one?” [Laughs]

BME: Who are some of your favorite artists right now?

BR: Well, my son Charlie for one. All the guys at Spotlight, Bryan and Steve and Norm, I love Bert Krak and Steve Boltz, Richard Stell, Tim Hendricks, Jack Rudy…

BME: And with how popular tattooing has gotten, do you think it’s going to stay or come and go in waves?

BR: I thought it was gonna be done 15 fuckin’ years ago. “Look at this, it’s gotta go downhill, it’s peaked out.”

BME: Could you have ever imagined there’d be a time with television shows about tattooing?

BR: No. Hey, listen, when I started out, I couldn’t even imagine that there’d be tattoo magazines. Now you can go to the newsstand and pick up five magazines and you’ve got a global view of what’s going on at this very moment. Me, if I wanted to find a fuckin’ dragon, I went to the library for eight hours and then went to the 25-cent Xerox machine, copied a dragon and traced it and made sure nobody was looking at me.

I remember I used to ride my motorcycle cross-country every year and I used to like to stop in the small towns where they had that good old country home cookin’, and I’d ride up on my bike and everyone would be scared of me—within 10 minutes I’d see the local sheriff—and they didn’t bother me, but they just wanted to make sure I was just getting something to eat and getting gas and was going to keep going. [Laughs] Now, I haven’t done it in a while, but the last few times I did it, I stopped in the same places and now the waitresses would say, “Oh, those are great tattoos!” They’d get the busboys and the dishwashers and everybody would be out front showing off their tattoos—this is in the very same towns! It’s everywhere. Every little town across the United States has a tattoo shop now.

BME: Is that a positive thing, though? Or do you think they should weed out some of the lesser shops?

BR: Well, that’s what we were saying, the health departments want to make sure everything’s sterile, you got a foot pedal and hot water and sinks and you wash everything down with hydrochloric acid and all that crap, but I’ve seen shops that were absolutely immaculate, you could eat off the fuckin’ floor, all the best equipment, all the expensive shit, everything’s wrapped in prophylactics, and they have the shittiest fuckin’ artists in the world. They don’t govern that. It’s art, who says it’s good or bad? Somebody might like what this guy does, but to me it’s absolute fucking garbage. The guy should have his fuckin’ thumbs cut off, at least. But they don’t regulate that, and that’s what needs to be regulated. Look how many unfortunate people in all good faith walk into some of these shops and throw their money down, and they’re getting fucked up and having their money taken from them. And there are a lot of them.

BME: You’d think with as many good artists as there are now, the worse ones will be exposed eventually.

BR: They don’t care, man. Like I said, they’re going in to get a pack of cigarettes. That’s what it is to them. They don’t know about all that stuff. It’s always been that way. I’ve known guys—who will remain nameless—who’ve been tattooing for 47 years that are just terrible. That’s all they’ll ever be, just sitting there and fuckin’ people up forever. But they’re people you’ve never heard of. Most people that you’ve heard of, that have been around…I just saw Maurice [Lynch] was in here, a lot of people don’t know who that is. That’s Tahiti Felix’s son, who just turned 75, and when I worked in Santa Ana, I used to see his Felix’s Marine Corps stuff come through, and it’s still ingrained in my brain. The first eagle, globe and anchor I saw—I’d seen work at The Pike and all they did there, but I’d never seen too much other work that I thought was good. I just remember seeing this guy’s arm, this was 38 years ago, and it’s as plain in my mind as if I saw it yesterday. That’s all those guys did. They don’t try to invent nothing, they don’t try to get out of the realm of their own shops, they just did good, simple tattoos—and a lot of them. Not because it was cool, not because they thought something looked like a good gimmick, they just did it. There was no reason. They were there, and that’s what they did. And guys like Bob Shaw and Col. Todd, they were just pure-hearted tattoo artists, there were no lines about how this is cool or trendy or fashionable or anything else. They just did it, man.

You’d see this for years, man, breaking in at The Pike? Guys just came in and did this stuff. Sailor Jerry just did it. They weren’t on T.V. Journalists? People like you? They’d throw them out. “Hey, wanna be in the paper?” “No, just get the fuck outta here.” They didn’t want to have anything to do with it. People get into it now and they have a lot of pride, a lot of self-satisfaction. You get to be a big-shot, it’s cool, you make a living. But, some people? Some people were just thrown on the ground and they fell down a hole and that’s where they are. They’re never gonna be anything else.

Visit Bob and his crew online at SpotlightTattoo.com. All paintings featured by Bob Roberts. All photos from Tattoo Hollywood by Phil Barbosa and Thaddeus Brown.