It’s been a very long time since I’ve written a body modification editorial. I don’t really have time to do it on a regular basis, but after some private discussion on the subject of the assumed illegality of dermal punches — and becoming fed up with fifteen years of legal urban legends on the subject — I felt compelled to expound on this subject.

PIERCING WITH A DERMAL PUNCH:

PRACTICING MEDICINE WITHOUT A LICENSE,

OR ETHICAL BODY MODIFICATION?

There has been a lot of debate over the past two decades over the use by body piercers of dermal punches (more accurately known as biopsy punches, as they are used by doctors to core out pieces of flesh for analysis). Even though at this point virtually all piercers agree that for certain procedures the dermal punch is a superior and safer tool, many American piercers avoid them and have expressed legal concern over the tool being a “Class II medical device” and this potentially putting them at risk of charges of practising medicine without a license or similar prosecution — or to use a more culturally accurate word, persecution.

In short, the essay will make the case that medical labelling is not only irrelevant to the piercing community, but that it is important that it not be a part of the discussion. I will seek to dispel the persistent myth that dermal punches as used by body piercers are a federally regulated device, and make the case that by perpetuating this myth, the piercing industry both cripples progress and creates new legal risk. Please note however that my argument is regarding federal medical device regulations, and that several state and county US jurisdiction may have secondary tool laws specific to body piercing that are directly relevant to piercers. While I feel these laws were created in error and need to be repealed, they are not the subject of this essay.

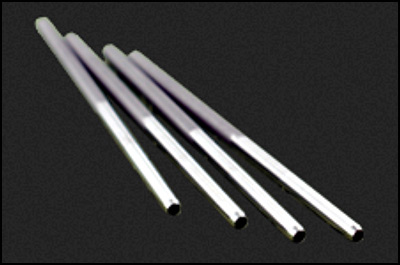

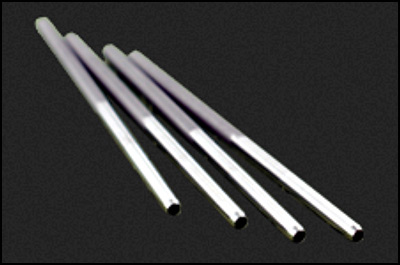

Disposable Dermal Punches (Biopsy Punches)

Before discussing the law, I want to point out the obvious history of the piercing needle. The piercing needle is of course based on the hollow medical hypodermic needle, and is used by the piercing community in one of two forms historically. In Europe and South America, it was common to use a cannula needle, similar to what is used for installing an IV drip, which is a hollow metal needle with a removable plastic sheath. The piercing was done with the two parts together, and once through the body, the metal part was withdrawn, leaving a plastic tube in the piercing. The jewelry was then inserted into this tube, which was then withdrawn, acting like a sort of taper to install the jewelry in the piercing. In the United States and Canada it was more common for piercers to purchase hypodermic needles of the sort that were mounted on the end of syringes to inject medication in a medical or veterinary context. Because these needles contained hubs for mounting on the syringes, piercers would cut off or otherwise remove the hubs prior to piercing, turning them into the simple needles (metal tubes that have a sharp bevel on one end and are flat on the other) that are in common use today.

From left to right: Hubbed hypodermic needles, catheter needles, modern piercing needles.

n time, converting the medical device fell out of favour, and companies began manufacturing piercing needles purely for the body piercing industry. This was for two main reasons — first, to distance themselves from using a medical device and any potential legalities and regulatory issues that might carry with it. Second, to provide a product that was of consistent quality and had a bevel design better suited to the needs of the body piercing community. However, it is important to recognize that the piercing needle’s genesis and nature is objectively a repurposed medical device.

I should also at this point very briefly comment on what are being called “O-needles” or “chamfer needles”. A normal needle has a diagonal bevel, but these have a bevel that runs perpendicular to the length of the needle. It is essentially a biopsy punch without the plastic handle (although a portion of the metal may be textured to act as a handle), just like a piercing needle is a hypodermic syringe needle without the plastic hub. It works like a biopsy punch in that instead of cutting a curved slot, it “cores” out a small circle of flesh, which, as with dermal punches, makes certain piercings such as cartilage work heal faster and with less scarring and other complications by relieving the pressure on the surrounding tissue. As I write this these new “needles” are being made only in smaller sizes (12ga and below) — but even an 18ga punch is superior to an 18ga needle in some circumstances so I’m not complaining! It is my hope that in time they will be available larger, but at the time of this writing, only “medical” dermal punches are available in larger sizes, with 8mm (approximately 0ga) being a popular size for conch punching. While I am very pleased that the piercing industry is beginning to manufacture punches themselves, and all things being equal, I would much rather see us making all our tools in-house, until both deeper market penetration has been achieved and larger sizes are available many piercers are still in the position of needing tools that were ostensibly made by the manufacturer primarily as a “medical device”.

Chamfer needles made by Sharpass Needles (the grey section is a rougher area for grip).

Now, on to the law itself. You can read an overview here:

www.fda.gov/MedicalDevices/DeviceRegulationandGuidance/GuidanceDocuments/ucm070958.htm

A careful reading should make it clear that the majority of these rules have to do with labelling regulations and other issues relevant primarily to device manufacturers. It is not a set of laws discussing the criminal matters of possession or use as one would have for example with opiate-based medications. No requirements are put forward for the possession of these devices, so while you will be charged as a drug dealer for possessing a bottle of OxyCodone without authorization, you face no such charges for possessing a case of dermal punches. That said, it is important to again note that some local health board regulations governing piercing may well ban the use of dermal punches, and in those cases their simple possession can affect shop licensing. The FDA however makes no such federal ban.

While it is true that the legal definition of the use of dermal punches, scalpels, or piercing needles to perform the procedures common to body piercing has never been tested in court, it is my strong opinion that none of these, when used in the context of body piercing (implants or tongue splitting may well be a different matter) meets the legal definition of “practising medicine”. As such, it is my opinion that once a “medical device” has been repurposed as a “piercing device”, and is being used in a completely different and non-medical context, that these regulations are no longer relevant. The fact that a needle or a biopsy punch is a medical device is relevant to the manufacturer that sells it to the medical community, but it is not relevant to the piercing community who are not doctors and are not acting as doctors. This statement also holds for the S&M and sex store market, which of course also appropriates medical devices in their own way.

Perhaps it is easier to understand why the use of dermal punches is not per se evidence of practising medicine when we examine other items that are also categorized in the regulations as Class II medical devices. For example, motorized wheelchairs are a Class II medical device, just like biopsy punches. Clearly it is sensible that there be regulations in place governing the manufacture and sale of wheelchairs to the medical industry. However, it does not from that stand that all use of wheelchairs is medical in nature or governed by medical law, or that one can be charged for “practising medicine” due to the possession, use, or misuse of wheelchairs. For example, it is perfectly legal — if a bit foolhardy — to organize a wheelchair racing league. You do not need a medical degree to do this. You do not need to be a paraplegic with a prescription from your doctor for the wheelchair. You do not need medical licensing to be a wheelchair mechanic and repurpose or modify the wheelchairs for racing.

The same applies to dermal punches. It’s only a medical device when you’re using it for medicine. If you want to use it for piercing, then you only need to concern yourself with the piercing regulations. As I said, in some jurisdictions, the piercing-specific regulations deal with these in both positive and negative manners depending on who wrote those regulations, although in most they are not specifically mentioned or restricted. In either case, these are piercing regulations, not medical regulations. Those FDA rules are separate and unrelated. And if you want to put a condom on a dermal punch and violate it in ways I don’t want to know about, that’s your business, and again, you don’t need to be a doctor to do it. Admittedly you may need a doctor afterwards, but that still doesn’t make your initial perverse act with the dermal punch medicine.

I am certain that in the future we will see more tools and techniques leak over from the medical field into body piercing and body modification as a whole. Some of the more popular tools will eventually be manufactured by the body modification industry, but not all of them. This issue does not end when the debate on dermal punches ends, or when “O-needles” effectively dominate the market.

It should now be clear that when piercing professionals worry that they should avoid medical devices such as biopsy punches that by the law, this has nothing to do with the regulation itself. It is solely related to how it is being used. Charges related to the unlicensed practise of medicine are related to the act, not the tool. That is, if you do liposuction using a modified home vacuum cleaner, rather than using appropriate medical tools, you are still practising medicine without a license. However, if you use real liposuction tools in an art installation, it is not medicine. What that means is that when a piercer makes the statement that performing a dermal punch procedure is risking such charges, what the law hears is that they are making the very clear claim that the piercing procedure itself is of a medical procedure. Ipso facto, body piercing can not be done by amateurs and should only be performed by doctors. Clearly this is a self-destructive line of thinking by the piercing community, to say nothing of being objectively incorrect, both culturally and legally — for the past decade or more, there are health boards in nearly every jurisdiction specifically regulating piercing completely distinct from medicine. Obviously piercing and medicine are distinct fields.

One last note on the FDA’s regulations on medical device labelling. Stating the obvious, historically the manufacturers of tools used in piercing have been concerned only with the medical community (since they were medical device manufacturers having their products repurposed without their consent or knowledge) and as such have always complied with the FDA’s medical device regulations. However, now that we are making many of our own implements — both piercing needles of the traditional sort and “O-needles” — the new manufacturers do not comply with any of those regulations, even though they are making tools that are arguably very close to the medical devices we are emulating and appropriating (and could in fact be used in medical procedures such as biopsies). I want to urge individual piercers, professional organizations such as the APP, and manufacturers of piercing equipment to be extremely careful about the rhetoric they use calling piercer’s use of dermal punches “medical” or in referring to these tools as “medical devices”. By not stating in the clearest possible terms that “piercing is not medicine” and that tools used by piercers (no matter what the source) are not “medical devices”, we put ourselves at risk of these regulations being unfairly applied to piercers, or more likely, piercing tool manufacturers. We must take care to not allow our caution in avoiding persecution to be used against us in bringing the law down upon us in new and unexpected ways. I feel the best way to do this is by taking a hard-line stance that medical regulations are completely irrelevant and unrelated to the piercing industry, since we are in the business of the ancient art of body piercing, and not that of modern medicine.

So please, let’s drop the fear-mongering. All we do when we promote falsehoods like this is feed into the paranoia of ignorant legislators that may be eavesdropping on our conversations, and use them to write unfair piercing regulations which block piercers from using the best and most ethical tools available to them. For piercing to continue progressing and moving forward, it is important that piercing is not frozen and “locked down”, but that we can innovate and seek out the best possible methods of performing this ancient yet still evolving art form.