(Editor’s note: This article was first published in The Point, the publication of the Association of Professional Piercers. Since part of BME’s mandate is to create as comprehensive and well rounded an archive of body modification as possible, we feel these are important additions.

Paul King, the article’s author, has given BME permission to publish a series of articles he wrote for The Point that explore the anthropological history behind many modern piercings. This is another in that series.)

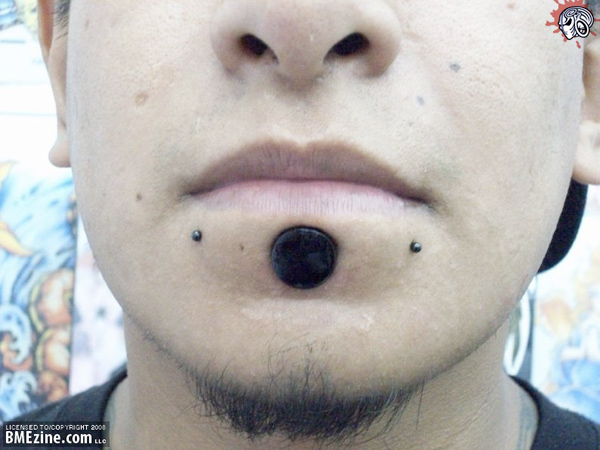

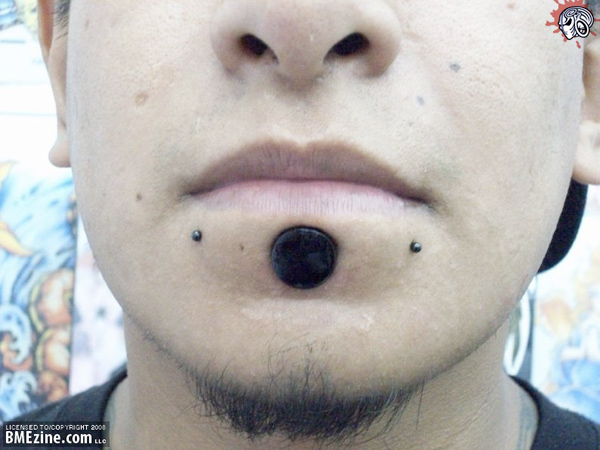

Current Western piercing culture has defined the centered piercing just under the lower lip as a labret, though historically, anthropologists have referred to piercings anywhere around the mouth and cheek as labrets. For the sake of this article, consider piercings currently referred to as Monroe, Beauty Mark, Madonna, Philtrum, cheek and side lip as falling into the category of labret.

Fellow piercing geeks will enjoy knowing that contrary to popular urban myth, “labret” is not a French word. It is actually English, derived from Latin and created sometime in the nineteenth century.1 The “t” is to be pronounced, not silent. Labret (\La’ bret\) is formed by the compounding of the Latin word labrium, meaning “lip,”2 and –et, meaning “small” or “something worn on.”3 There is even an archaic form of the word, “labretifery,” which means, “the practice of wearing labrets.”4 How fancy is that? (OK, I’m a geek.)

After the 2003 APP conference in Amsterdam, I traveled to Berlin to visit the Babylonian exhibit at the famous Pergamon Museum. While wandering the halls of the Mesopotamian exhibits I stumbled across a stele from 671 B.C.E. of King Esahaddon of Assyria. The (approximately) six-foot-tall stone monument was excavated from the citadel of Sam ‘al Zinjirli. The carving depicts the king holding two ropes in his left hand that attach to rings in two prisoners’ lips. This is not my interpretation, but the museum curator’s description, listed on the artifact.

The book Marks of Civilization5 contains perhaps the best collective information on North American labrets. The wearing of labrets was widely practiced by the Eskimos and Aleuts of Alaska in prehistoric and early post-contact eras, yet disappeared within three generations due to intense efforts on the part of Christian missionaries. One essay lists the largest labret found measuring 11.9 cm and weighing seven ounces. The first European record reporting the Aleut labret dates back to 1741, though we know Russian fur traders had contact before that. The practice of wearing labrets varied all over Unalaska. In some areas only boys would get their lips pierced, while in others only girls. In some regions the custom was to pierce infants, while others were pierced at puberty. The reasons varied as well. For a boy it could be part of his induction into manhood, for a girl, part of her coming of marrying age, and for some tribes as part of the marriage ceremonies. Most of the indigenous people believed in animal reincarnation; this sympathetic association was revealed by the wearing of a whale-tail shaped labret or paired lateral labrets imitating a walrus’s tusks.

In South America only the boys of the Suya tribe have their lips pierced, and the lip plugs are painted red for confidence in speech, war, ideas, and so on. Both the boys and girls get their ears pierced once they reach adolescence. They are then expected to “listen” and act like adults, etc. The plugs are painted white for passivity and good listening.

Kichepo and Surma women of Southeastern Sudan in Africa have the largest lip piercings in the world; the elder, more respected women will sometimes have their lips stretched over ten inches in diameter! Some myths say it is to imitate birds, while other stories say it’s to eat less, and thus be less of a burden, or to gossip less, or possibly to be made less attractive to other tribes and slave traders to help prevent kidnapping.

In pre-Columbian Mesoamerica, the indigenous people would adorn their lips with expertly worked pieces of obsidian, semiprecious stone and gold. These lip piercings held great significance of both religious and social status and were considered objects of great beauty. The APP’s International Liaison, Alicia Cardenas [Ed. note: Alicia is no longer in this position] will be writing an article of greater depth into Mesoamerican lip piercing, including whether or not the Olmec — from 1100 B.C.E. to 200 C.E., the oldest known Mesoamerican advanced civilization — practiced lip piercing. If they did, the Olmec would be the oldest known people to engage in labretifery!

__________

1 Collin’s English Dictionary, 2000.

2 Webster’s Dictionary, 1913.

3 American Heritage Dictionary 4th edition, 2000.

4 www.quinion.com

5 Marks of Civilization, Edited by Arnold Rubin, University of California, Los Angeles, 1992. ISBN 0-930741-12-9, Essays of interest: Labrets and Tattooing in Native Alaska by Joy Gritton and Women, Marriage, Mouths and Feasting: The Symbolism of Tlingit Labrets by Aldona Jonaitis.

My usual disclaimer: I am not an anthropologist. From time to time, there will be errors. Please be understanding and forth coming if you have any information you would like to share.

* * *

Please consider buying a membership to BME so we can continue bringing you articles like this one.